Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Bullous diseases

Epidermolysis bullosa

Epidermolysis

bullosa

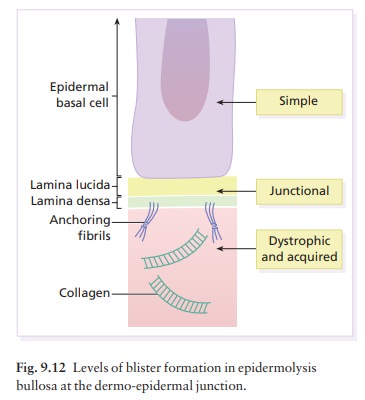

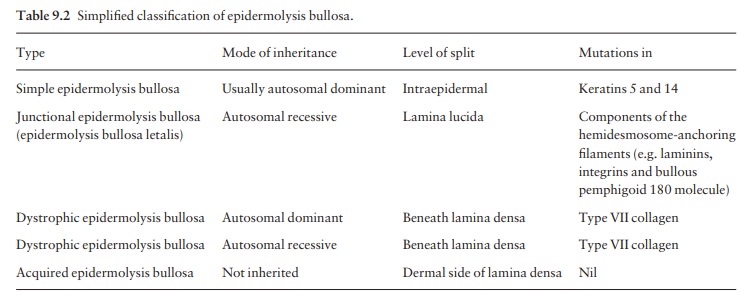

There are many types of epidermolysis bullosa: the five main ones are listed in Table 9.2. All are charac-terized by an inherited tendency to develop blisters after minimal trauma, although at different levels in the skin (Fig. 9.12). The more severe types have a catastrophic impact on the lives of sufferers. Acquired epidermolysis bullosa is not inherited and was discussed earlier.

Simple epidermolysis bullosa

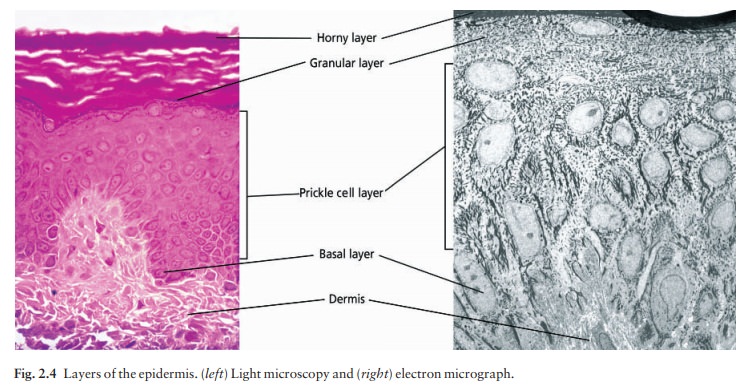

Several subtypes are recognized, of which the most common are the Weber–Cockayne (mainly affecting the hands and feet) and the Dowling–Meara (featur-ing herpetiform blisters on the trunk) types. Most are inherited as autosomal dominant conditions and are caused by abnormalities in genes responsible for pro-duction of the paired keratins (K5 and K14) expressed in basal keratinocytes (see Fig. 2.4). Linkage studies show that the genetic defects responsible for the most common types of simple epidermolysis bullosa lie on chromosomes 17 and 12.

Blisters

form within or just above the basal cell layers of the epidermis and so tend to

heal without scarring. Nails and mucosae are not involved. The problems are

made worse by sweating and ill-fitting shoes. Blistering can be minimized by

avoiding trauma, wearing soft well-fitting shoes and using foot powder. Large

blisters should be pricked with a sterile needle and dressed. Their roofs

should not be removed. Local antibiotics may be needed.

Junctional epidermolysis bullosa

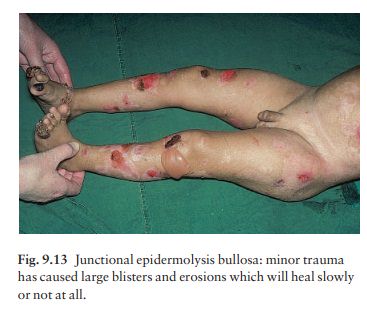

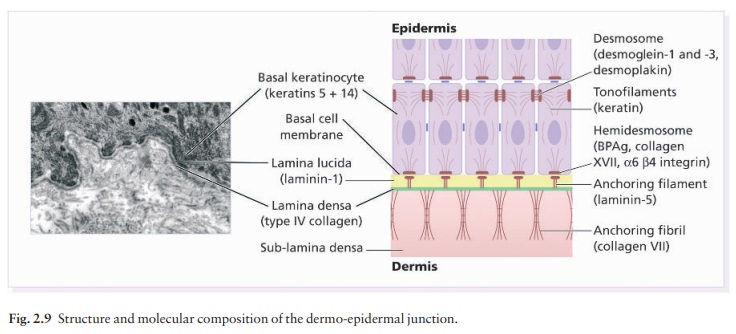

The

abnormalities in the basal lamina include loss of anchoring filaments and defective

laminins (; see Fig. 2.9). This rare and often lethal condition is evident at

birth. The newborn child has large raw areas and flaccid blisters, which are

slow to heal (Fig. 9.13). The peri-oral and peri-anal skin is usually involved,

as are the nails and oral mucous membrane. There is no effective systemic

treatment. Hopes for the future include adding the normal gene to epidermal

stem cells, and then layering these onto the denuded skin.

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

There are many subtypes, all of which probably result from abnormalities of collagen VII, the major struc-tural component of anchoring fibrils

Autosomal dominant dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

In

this type blisters appear in late infancy. They are most common on friction

sites (e.g. the knees, elbows and fingers), healing with scarring and milia

formation. The nails may be deformed or even lost. The mouth is not affected.

The only treatment is to avoid trauma and to dress the blistered areas.

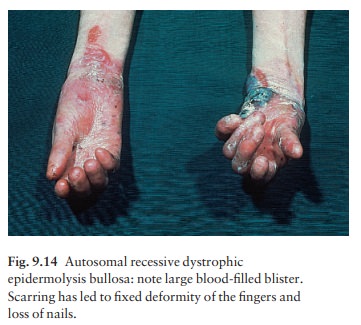

Autosomal recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

In

this tragic form of epidermolysis bullosa, blisters start in infancy. They are

subepidermal and may be filled with blood. They heal with scarring, which can

be so severe that the nails are lost and webs form between the digits (Fig.

9.14). The hands and feet may become useless balls, having lost all fingers and

toes. The teeth, mouth and upper part of the oesophagus are all affected;

oesophageal strictures may form. Squamous cell carcinomas of the skin are a

late complication. Treatment is unsatisfactory. Phenytoin, which reduces the

raised dermal collagenase levels found in this variant, and systemic steroids

are disappointing. It is especially important to minimize trauma, to prevent

contractures and web formation between the digits, and to combat anaemia and

secondary infection. Referral to centres with expertise in management of these

patients is strongly recommended.

Related Topics