Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Bullous diseases

Pemphigus

Bullous

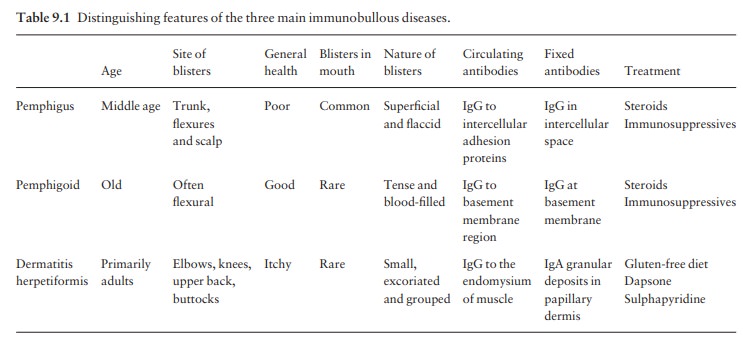

disorders of immunological origin

In

pemphigus and pemphigoid, the damage is done by autoantibodies directed at

molecules that norm ally bind the skin.

This type of mechanism has not yet been proven for dermatitis herpetiformis; but the characteristic deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig) A in the papillary dermis, and an association with a variety of autoimmune dis-orders, both suggest an immunological basis for the disease.

Pemphigus

Pemphigus

is severe and potentially life-threatening. There are two main types. The most

common is pemphigus vulgaris, which accounts for at least three-quarters of all

cases, and for most of the deaths. Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of

pemphigus vulgaris. The other important type of pemphigus, superficial

pemphigus, also has two variants: the generalized foliaceus type and localized

erythema-tosus type. A few drugs, led by penicillamine, can trigger a

pemphigus-like reaction, but autoanti-bodies are then seldom found. Finally, a

rare type of pemphigus (paraneoplastic pemphigus) has been described in

association with a thymoma or an under-lying carcinoma; it is characterized by

unusually severe mucosal lesions.

Cause

All

types of pemphigus are autoimmune diseases in which pathogenic IgG antibodies

bind to antigens within the epidermis. The main antigens are des-moglein 3 (in

pemphigus vulgaris) and desmoglein 1 (in superficial pemphigus). Both are

cell-adhesion molecules of the cadherin family (see Table 2.5), found in desmosomes.

The antigen–antibody reaction interferes with adhesion, causing the

keratinocytes to fall apart.

Presentation

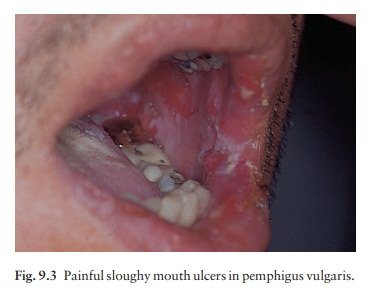

Pemphigus

vulgaris is characterized by flaccid blisters of the skin (Fig. 9.2) and mouth

(Fig. 9.3) and, after the blisters rupture, by widespread painful erosions.

Most patients develop the mouth lesions first.

Shearing stresses

on normal skin can cause new erosions to form (a positive Nikolsky sign). In

the vegetans variant (Fig. 9.4), heaped up cauliflower-like weeping areas are

present in the groin and body folds. The blisters in pemphigus foliaceus are so

superficial, and rupture so easily, that the clinical picture is dominated more

by weeping and crusting erosions than by blisters. In the rarer pemphigus

erythematosus, the facial lesions are often pink, dry and scaly.

Course

The

course of all forms of pemphigus is prolonged, even with treatment, and the

mortality rate of pemphigus vulgaris is still at least 15%. Superficial

pemphigus is less severe. With modern treatments, most patients with pemphigus

can live relatively normal lives, with occasional exacerbations.

Complications

Complications

are inevitable with the high doses of steroids and immunosuppressive drugs that

are needed to control the condition. Indeed, side-effects of treat-ment are now

the leading cause of death. Infections of all types are common. The large areas

of denuda-tion may become infected and smelly, and severe oral ulcers make

eating painful.

Differential diagnosis

Widespread

erosions may suggest a pyoderma, impetigo, epidermolysis bullosa or ecthyma.

Mouth ulcers can be mistaken for aphthae, Behçet’s disease or a herpes simplex

infection.

Investigations

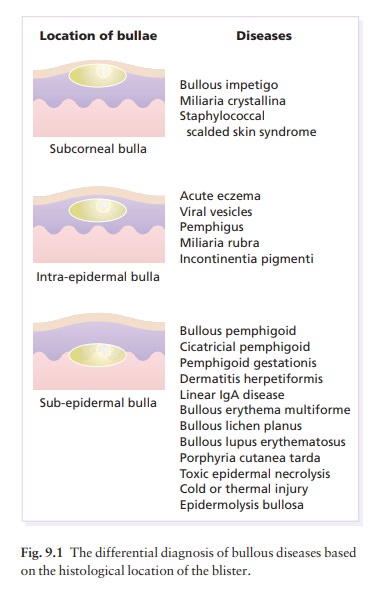

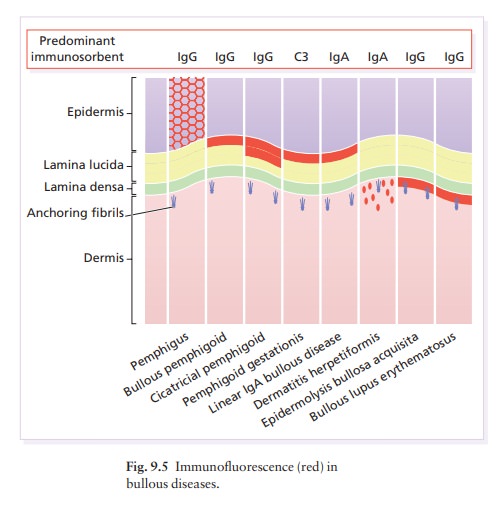

Biopsy

shows that the vesicles are intraepidermal, with rounded keratinocytes floating

freely within the blister cavity (acantholysis). Direct immunofluorescence of adjacent normal skin shows intercellular

epidermal deposits of IgG and C3 (Fig. 9.5). The serum from a patient with

pemphigus contains antibodies that bind to the desmogleins in the desmosomes of

normal epidermis, so that indirect immunofluorescence can also be used to confirm the diagnosis.

The titre of these antibodies correlates loosely with clinical activ-ity and

may guide changes in the dosage of systemic steroids.

Treatment

Because

of the dangers of pemphigus vulgaris, and the difficulty in controlling it,

patients should be treated in a specialized unit. Resistant and severe cases

need very high doses of systemic steroids, such as prednis-olone 80–320 mg/day, and the dose is dropped only

when new blisters stop appear-ing. Immunosuppressive agents, such as

azathioprine or cyclophosphamide and, recently, mycophenylate mofetil, are

often used as steroid-sparing agents. New and promising approaches include

plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin as used in other auto-immune

diseases. Treatment needs regular follow-up and is usually prolonged. In

superficial pemphigus, smaller doses are usually needed, and the use of

top-ical corticosteroids may help too

Related Topics