Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Differential Diagnosis - Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Differential Diagnosis

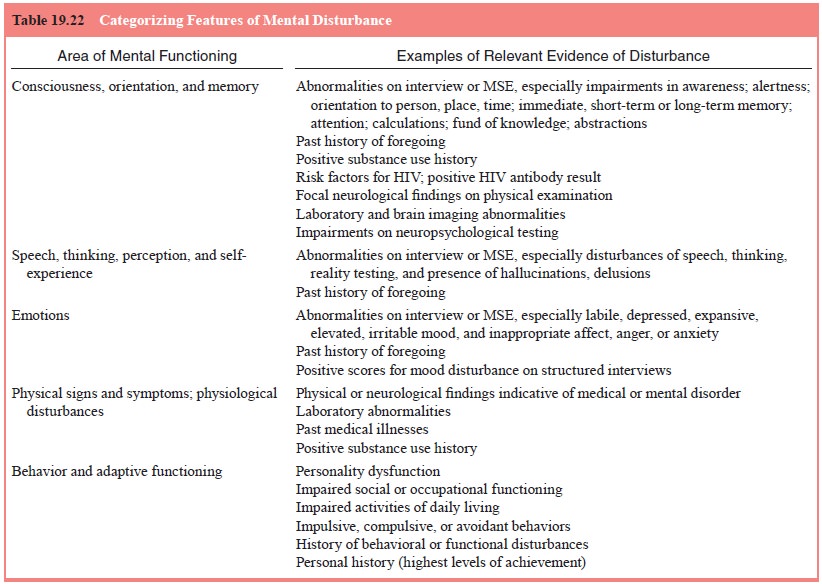

The differential diagnosis is best approached by

organizing the information obtained in the psychiatric evaluation into five

domains of mental functioning according to the disturbances revealed by the

evaluation. After organizing the in-formation into these five domains, the

psychiatrist looks for the psychopathological syndromes and potential diagnoses

that best account for the disturbances described. A complete diagnostic

evaluation includes assessments on each of the five axes of DSM-IV-TR (Table

19.22).

Disturbances of consciousness, orientation and

memory are most typically associated with delirium related to a general medical

condition or a substance use disorder. Memory impair-ment and other cognitive

disturbances are the hallmarks of de- etiology. It is important to elicit risk

factors for HIV infection and, when they are present, to encourage voluntary

HIV anti-body testing. Neuropsychological testing is particularly useful in the

diagnosis of subcortical dementia, such as that caused by Huntington’s disease

and HIV infection. Dissociative disorders and severe psychotic states may also

present with disturbances in this domain without evidence of any medical

etiology. Cognitive impairment caused by mental retardation is established by

intel-ligence testing.

Disturbances of speech, thinking, perception and

self-experience are common in psychotic states that can be seen in patients

with such diagnoses as schizophrenia and mania, as well as in central nervous

system dysfunction caused by substance use or a medical condition. Disturbances

in self-experience are also common in dissociative disorders and certain

anxiety, somato-form and eating disorders. Cluster A personality disorders may

be associated with milder forms of disturbances in this domain (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Disturbances of emotion are most typical of affective

and anxiety disorders. These disturbances may also be caused by substance use

disorders and general medical conditions. Mood and affect disturbances

accompany many personality disorders and may be especially pronounced in

borderline personality disorder.

Physical signs and symptoms and any associated abnor-malities revealed by diagnostic medical tests and past medical history are used to establish the presence of general medical con-ditions, which are coded on Axis III. When a medical disorder is causally related to a psychiatric disorder, a statement of this re-lationship should appear on Axis I. Physical signs and symptoms may also suggest diagnoses of mood or anxiety disorders or states of substance intoxication or withdrawal. Physical symptoms for which no medical etiology can be demonstrated after thorough assessment suggest somatoform or factitious disorders or malin-gering, although the possibility of an as-yet-undiagnosed medical condition should still be kept in mind.

Information about behavior and adaptive functioning

is useful for diagnosing personality disorders, documenting psychosocial and

environmental problems on Axis IV, and as-sessing global functioning on Axis V.

This information is also useful for diagnosing most psychiatric disorders,

which typically include criteria related to abnormal behaviors and functional

impairment.

When all information has been gathered and

organized, it may be possible to reach definitive diagnoses, but sometimes this

must await further evaluation and the development of the comprehensive

treatment plan.

Initial Treatment Plan

The initial treatment plan follows the case

formulation, which has already established the nature of the current problem

and a tenta-tive diagnosis. The plan distinguishes between what must be

ac-complished now and what is postponed for the future. Treatment planning

works best when it follows the biopsychosocial model.

Biological Intervention

This includes an immediate response to any

life-threatening medical conditions and a plan for the treatment of other less

acute physical disorders, including those that may contribute to an al-tered

mental status. Prescription of psychotropic medications in accordance with the

tentative diagnosis is the most common bio-logical intervention.

Psychosocial Intervention

This includes immediate plans to prevent violent or

suicidal be-havior and address adverse external circumstances. An overall

strategy must be developed that is both realistic and responsive to the

patient’s situation. Developing this strategy requires an awareness of the

social support systems available to the patient; the financial resources of the

patient; the availability of services in the area; the need to contact other

agencies, such as child wel-fare or the police; and the need to ensure child

care for dependent children.

Initial Disposition

The primary task of the initial disposition is to

select the most ap-propriate level of care after completion of the psychiatric

evalua-tion. Disposition is primarily focused on immediate goals. After

referral, the patient and the treatment team develop longer term goals.

Hospitalization

The first decision in any disposition plan is

whether hospitaliza-tion is required to ensure safety. There are times when a

patient presents with such severe risk of harm to self or others that

hos-pitalization seems essential. In other cases, the patient could be managed

outside the hospital, depending on the availability of other supports. This

might include a family who can stay with the patient or a crisis team in the

community able to treat the patient at home. The more comprehensive the system

of services, the easier it is to avoid hospitalization. Because hospitalization

is associated with extreme disruption of usual life activities and in and of

itself can have many adverse consequences, plans to avoid hospitalization are

usually appropriate as long as they do not compromise safety.

Day Programs, Crisis Residences and Supervised Housing

These interventions provide ongoing supervision but

at a lower level than that available within the hospital. They are most often

used to treat patients with alcohol and substance use disorders or severe

mental illness. Crisis housing can be useful when a patient cannot safely

return home, when caregivers need respite, and when the patient is homeless.

Other forms of supervised hous-ing usually have a waiting period and may not be

immediately available.

There are many different types of and names for

day-long programming, including partial hospitalization, day treatment,

psychiatric rehabilitation and psychosocial clubs. Depending on the nature of

the program, it may provide stabilization, daily medication, training in social

and vocational skills, and treatment of alcohol and substance use problems.

Long-term day programs should generally be avoided if a patient is functioning

successfully in a daytime role, such as in a job or as a homemaker. In these

instances, referral to a day program may promote a lower level of functioning

than the patient is capable of.

Outpatient Medication and Psychotherapy

The most common referral after psychiatric

evaluation is to psy-chotherapy and/or medication management. In office-based

set-tings, the psychiatrist decides whether she or he has the time and expertise

to treat the patient and makes referrals to other practi-tioners as

appropriate. Hospital staff usually have a broad over-view of community

resources and refer accordingly. There are high rates of dropout when patients

are sent from one setting to another. These can be reduced by providing

introductions to the treatment setting and/or conducting follow-up to ensure

that the referral has been successful.

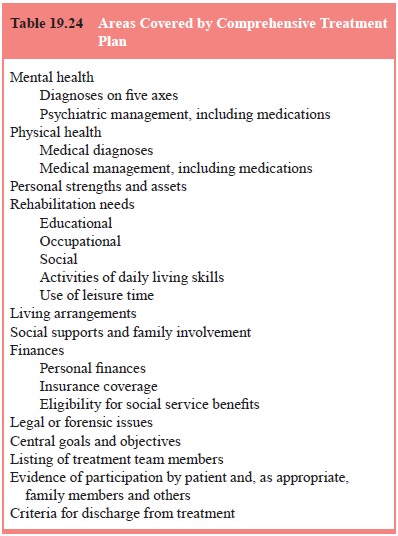

Comprehensive Treatment Planning

The psychiatric evaluation usually continues beyond

the ini-tial disposition. The providers assuming responsibility for the

patient, who may be inpatient staff, outpatient staff, or private

practitioners, complete the evaluation and take responsibility for developing

the comprehensive treatment plan. This plan covers the entire array of concerns

that affect the course of the patient’s psychiatric problems. In hospital

settings, the initial treatment plan is usually completed within 24 to 72 hours

after admission, followed by comprehensive treatment plan after more extensive

evaluation.

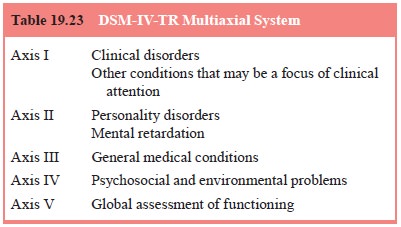

The comprehensive treatment plan usually includes

more definitive diagnoses and a well-formulated management plan with central

goals and objectives. For severely ill or hospitalized patients, every area is

usually covered (Table 19.23 and 19.24). It is best for the patient and, as

appropriate, the family, to have input into the plan. The comprehensive

treatment plan guides and coor-dinates the direction of all treatment for an

extended time, usually

months, and is periodically reviewed and updated.

For more focal psychiatric problems (e.g., phobias, sexual dysfunctions) and

more limited interventions (e.g., brief interpersonal, cognitive, and

be-havioral therapies in office-based practices), the comprehensive treatment

plan may focus on only several of the possible areas.

Related Topics