Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Limitations of Reliability and Validity

Limitations of Reliability and

Validity

Despite the obvious role of quantification in

neuropsychologi-cal testing, interpretation of test data ultimately depends on

the knowledge base, training and skill of the clinician. Neuropsy-chological

test scores are an indirect measure of the status of the brain, as contrasted

with direct measures of structure by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or

function by positron emission tomography (PET), functional MRI, or EEG. In a

psy-chiatric setting, where problems of motivation, effort, coopera-tion and

stage of the illness are ubiquitous, analysis of neuropsy-chological data must

go beyond the level of performance deficits because many studies have shown

performance to be especially affected by functional (emotional) factors.

Process analyses ori-ented to focal syndromes and focused on the relative

efficiency of the two sides of the body and hemispace may enhance predic-tive

validity.

The patient’s clinical state may change, and

repeated test-ing when the patient’s clinical status is optimal often clarifies

the nature of the diagnosis. Selective deficits found in the con-text of

otherwise good performance when patients are tested in their best state can be

considered most valid. Neuropsychologists must also take into account the

effect of medication on neuropsy-chological function and distinguish medication

effects from the patient’s adaptive ability. Different medications are likely

to produce different effects. For example, Trimble and Thompson (1986) have

demonstrated that, for epileptic patients and normal subjects, anticonvulsants

have negative effects on most measures of neuropsychological testing. On the

other hand, Cassens and colleagues (1990) have demonstrated that (traditional)

antipsy-chotic medications have negligible or mildly positive effects on most

measures of neuropsychological testing in chronic schizo-phrenia, with the

exception of a negative effect on motor per-formance. Spohn and Strauss (1989)

have indicated that typical antipsychotic medications tend to improve

attentional perform-ance, such as on versions of the CPT.

Structured Clinical Instruments and Rating Scales

Structured instruments and rating scales have been

developed primarily for research purposes. They allow investigators to compare

findings in different studies by ensuring that similar data and criteria have

been used to establish diagnoses and to measure the presence and severity of

psychiatric symptoms and their response to treatment. Many types of mental health

profes-sionals and, in some cases, nonclinicians can be trained to ad-minister

these rating scales.

Although most practicing clinicians do not commonly

use structured instruments to assess or follow-up patients, a small number of

rating scales have come to be used routinely in clini-cal practice. For

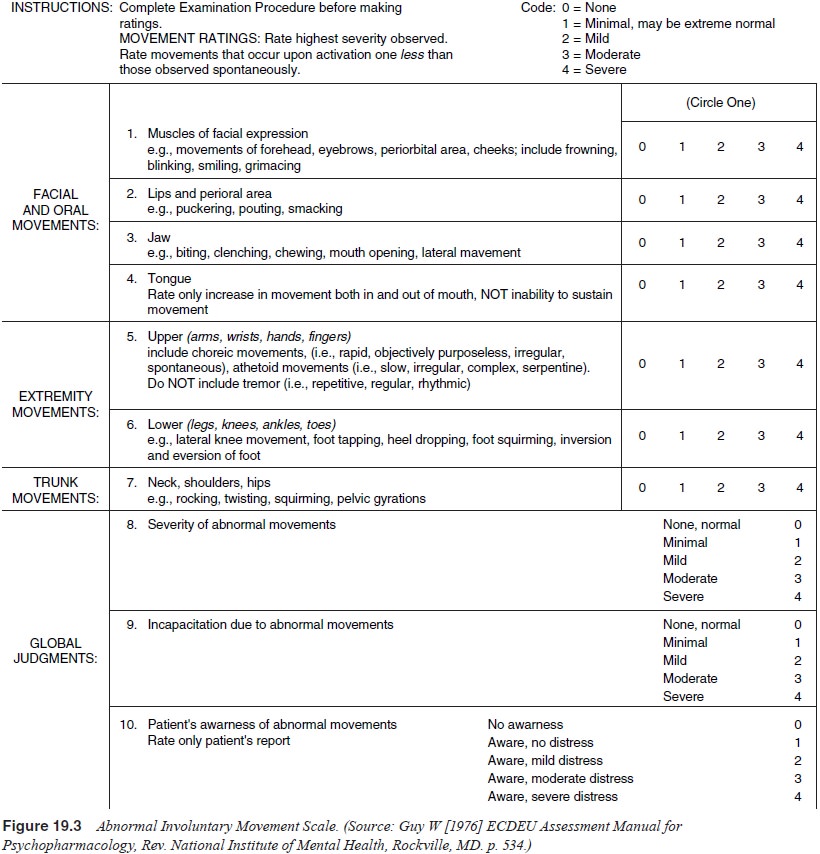

example, the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (Figure 19.3) is often used to

monitor patients receiving antipsychotic medication for the presence of tardive

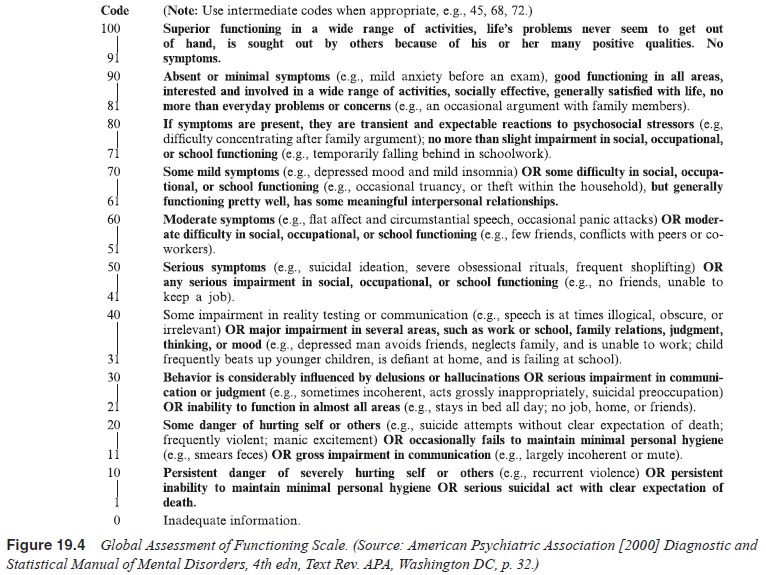

dyskinesia, and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (Figure 19.4), which

is a slight modification of the Global Assessment Scale, is now used in Axis V

in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, Fourth

Edition (DSM-IV-TR).

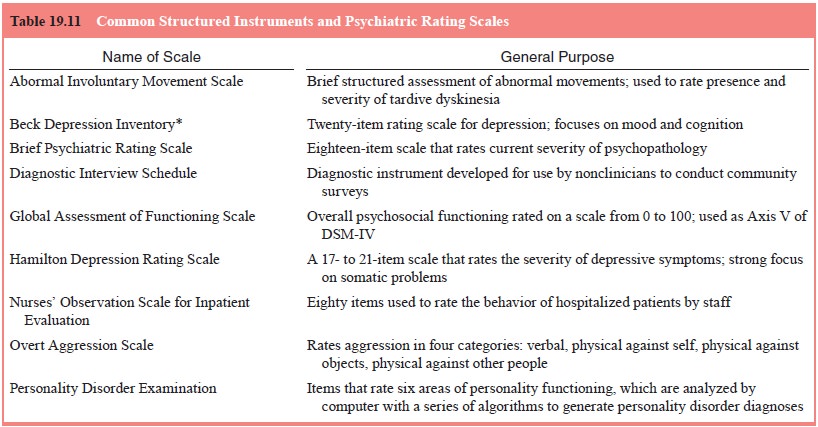

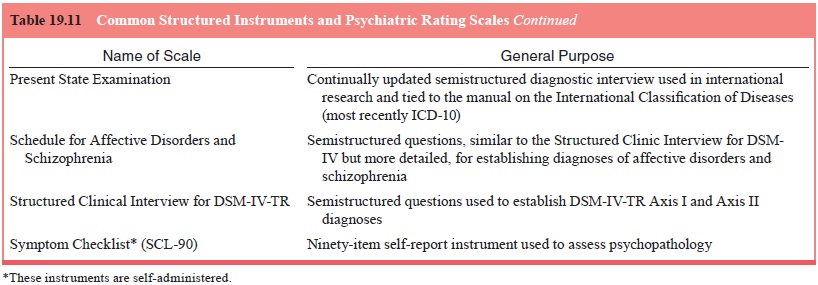

Table 19.11 shows some of the most commonly cited

struc-tured instruments and rating scales. Hundreds of other special-ized

scales are also in use to assess such diverse areas as person-ality disorder,

aggressive behavior, sexual practices, stressful life events and quality of

life.

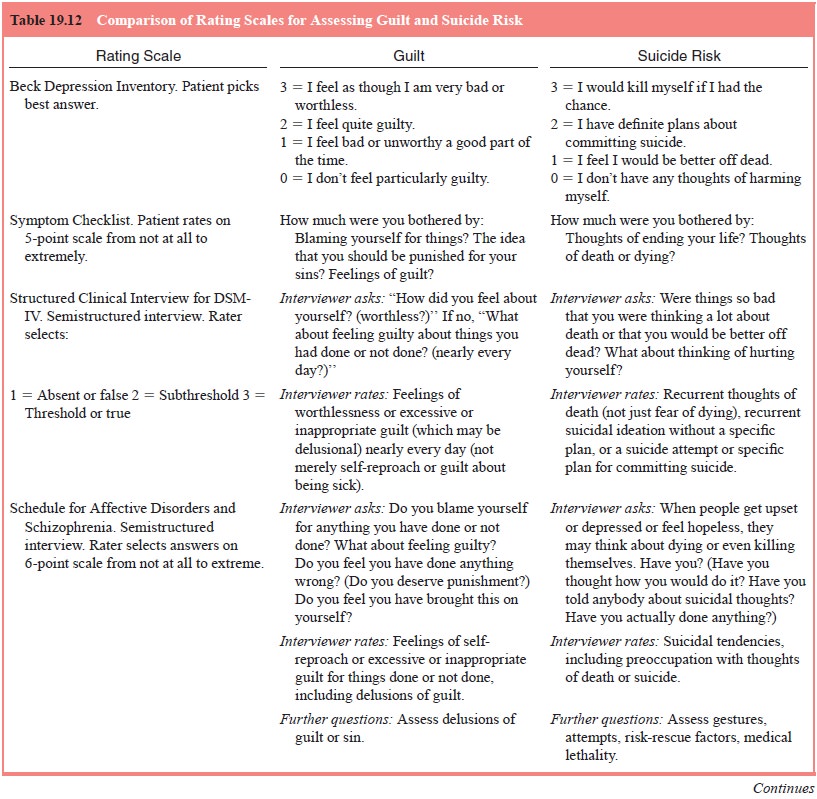

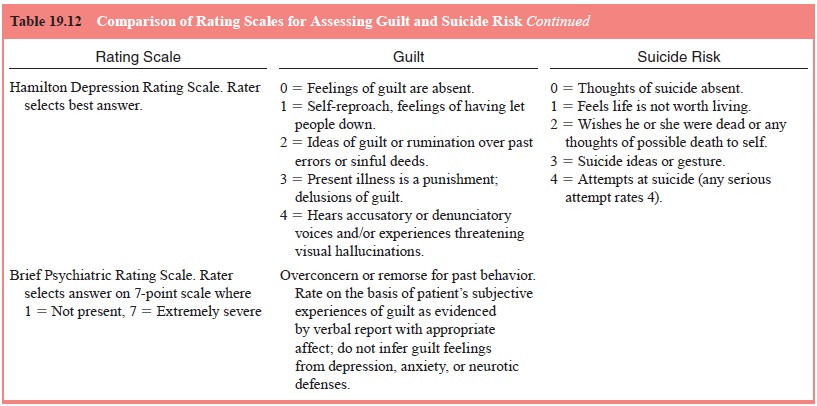

Table 19.12 gives an example of how these different

rat-ing scales approach the assessment of two symptoms: guilt, a purely

subjective state of mind, and suicide risk, an incli-nation that is assessed

using both subjective and behavioral components.

Related Topics