Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Treatment Planning - Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Treatment Planning

The psychiatric evaluation is the basis for

developing the case formulation, initial treatment plan, initial disposition

and com-prehensive treatment plan.

Case Formulation

The case formulation is the summary statement of

the immediate problem, the context in which the problem has arisen, the

tenta-tive diagnosis and the assessment of risk. The latter two areas are

described next in more detail.

Assessment of Risk

The assessment of risk is the most crucial

component of the for-mulation because the safety of the patient, the clinician

and oth-ers is the foremost concern in any psychiatric evaluation. Four areas

are important: suicide risk, assault risk, life-threatening medical conditions

and external threat.

Suicide Risk

The risk of suicide is the most common

life-threatening situation mental health professionals encounter. Its

assessment is based on both an understanding of its epidemiology, which alerts

the clinician to potential danger, and the individualized assessment of the

patient. Suicide is the eighth leading cause of death in the USA. In the past

century, the rate of suicide has averaged 12.5 per 100 000 people. Studies of

adults and adolescents who commit suicide reveal that more than 90% of them

suffered from at least one psychiatric disorder and as many as 80% of them

consulted a physician in the months preceding the event. An astute risk

as-sessment therefore provides an opportunity for prevention.

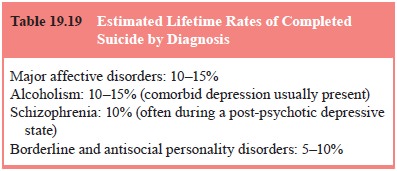

For those who complete suicide, the most common

diag-noses are affective disorder (45–70%) and alcoholism (25%). In certain

psychiatric disorders, there is a significant lifetime risk for suicide, as

listed in Table 19.18. Panic disorder is associated with an elevated rate of

suicidal ideation and suicide attempts but estimates of rates of completed

suicide are not well established.

Suicide rates increase with age, although rates

among young adults have been steadily rising. Women attempt suicide more often

than men, but men are three to four times more likely than women to complete

suicide. Whites have higher rates of sui-cide than other groups.

A patient may fit the diagnostic and demographic

profile for suicide risk, but even more essential is the individualized

assessment developed by integrating information

from all parts of the psychiatric evaluation. This includes material from the

present illness (e.g., symptoms of depression, paranoid ideation about being

harmed), past psychiatric history (e.g., prior attempts at suicide or other

violent behavior), personal history (e.g., recent loss), family history (e.g.,

suicide or violence in close relatives), medical history (e.g., presence of a

terminal illness) and the MSE (e.g., helplessness, suicidal ideation).

The most consistent predictor of future suicidal

behavior is a prior history of such behavior, which is especially worrisome

when previous suicide attempts have involved serious intent or lethal means.

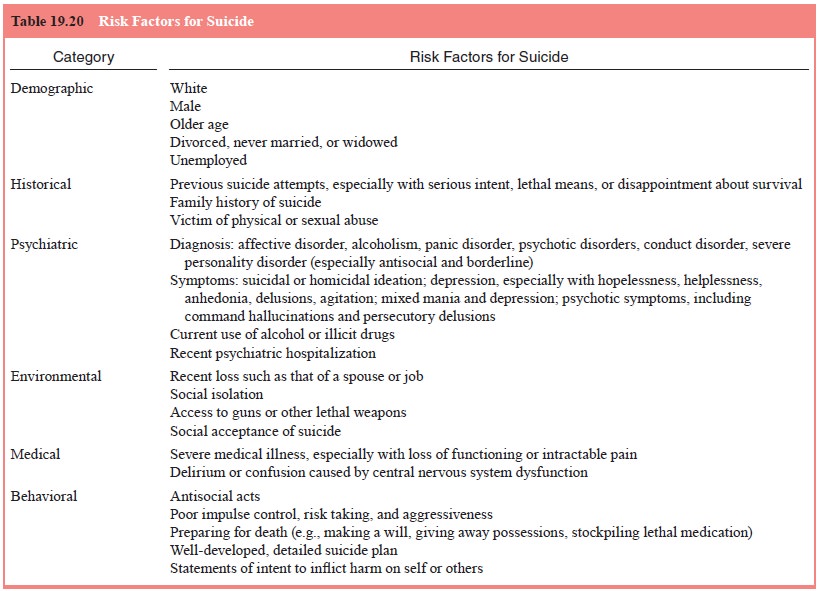

Among the factors cited as having an association with risk of suicide are

current use of drugs and alcohol; recent loss, such as of a spouse or job;

social isolation; conduct disorders and antisocial behavior, especially in

young men; the presence of depression, especially when it is accompanied by

hopelessness, helplessness, delusions, or agitation; certain psychotic

symp-toms, such as command hallucinations and frightening paranoid delusions;

fantasies of reunion by death; and severe medical ill-ness, especially when it

is associated with loss of functioning, in-tractable pain, or central nervous

system dysfunction. Table 19.19 lists risk factors for suicide. It should be

noted that assisted sui-cide is now more openly discussed among people with terminal

illnesses and has gained some measure of acceptability. None-theless, the vast

majority of people who are bereaved or suffer from a serious medical illness do

not end their lives by suicide. Adequate end-of-life care should forestall

requests for assisted suicide. Although suicidal intent may be lacking,

patients who are delirious and confused as a result of a medical illness are

also at risk of self-injury.

It is essential to be clear about whether the

patient has pas-sive thoughts about suicide or actual intent. Is there a plan?

If so, how detailed is it, how lethal, and what are the chances of rescue? The

possession of firearms is particularly worrisome, because nearly two-thirds of

documented suicides among men and more than a third among women have involved

this method

Factors that may protect against suicide include

convictions in opposition to suicide; strong attachments to others, including

spouse and children; and evidence of good impulse control.

In addition to the assessment of risk factors, it

is important to decide whether the possibility of suicide is of immediate

con-cern or represents a long-term ongoing risk.

Risk of Assault

Unlike those who commit suicide, most people who

commit vio-lent acts have not been diagnosed with a mental illness, and data

clarifying the relationship between mental illness and violence are limited.

The most common psychiatric diagnoses associated with violence are

substance-related disorders. Conduct disorder and antisocial personality

disorder, by definition, involve aggres-sive, violent and/or unlawful behavior.

In the absence of comorbid substance-related

disorders, most people with such major mental illnesses as affective dis-orders

and schizophrenia are not violent. But data from the Na-tional Institute of

Mental Health Epidemiological Catchment Area Study suggest that these diagnoses

are associated with a higher rate of violence than that found among individuals

who have no diagnosable mental illness. The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment

Study found this was only true for psychiatric patients with substance abuse

(Steadman et al., 1998).

Table 19.20 lists risk factors for violence. As

with suicide, the best predictor of future assault is a history of past

assaultInformation from the psychiatric evaluation that helps in this

as-sessment includes the present illness (e.g., preoccupation with vengeance,

especially when accompanied by a plan of action), psychiatric history (e.g.,

childhood conduct disorder), family his-tory (e.g., exposure as a child to

violent parental behavior), per-sonal history (e.g., arrest record), and the

MSE (e.g., homicidal ideation, severe agitation). Other predictors of violence

include possession of weapons and current illegal activities. There is

considerable overlap between risk factors for suicide and those for violence.

Life-threatening Medical Conditions

It is essential to consider life-threatening

medical illness as a po-tential cause of psychiatric disturbance. Clues to this

etiology can be found in the present illness (e.g., physical complaints),

family history (e.g., causes of death in close family members), medical history

(e.g., previous medical conditions and treatments), physi-cal examination

(e.g., abnormalities identified) and MSE (e.g., confusion, fluctuation in

levels of consciousness). Laboratory assessment, brain imaging and structured

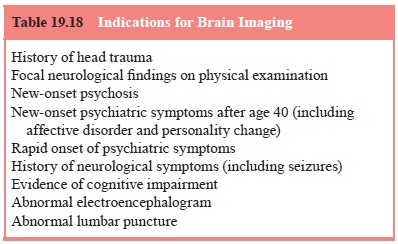

tests for neuropsychi-atric impairment may also be essential.

Probably the most common life-threatening medical sit-uations that the psychiatrist evaluates are acute central nerv-ous system changes caused by medical conditions and accom-panied by mental status alterations. These include increased intracranial pressure or other cerebral abnormalities, seve metabolic alterations, toxic states and alcohol withdrawal. Pa-tients may be at risk of death if these states are not quickly identified.

External Threat

Some patients who present for psychiatric

evaluation are at risk as a result of life-threatening external situations.

Such patients can include battered women, abused children and victims of

ca-tastrophes who lack proper food or shelter. Information about these

conditions is usually obtained from the present illness, the personal history

the medical history and physical examination.

Related Topics