Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Clinical Evaluation and Treatment Planning: A Multimodal Approach

Physical Examination

Physical Examination

The physical examination is an important part of

the compre-hensive psychiatric evaluation for several reasons. First, many

patients who present with psychiatric symptoms may have under-lying medical

problems that are causing or exacerbating the pre-senting symptoms. For

example, an agitated, delirious patient may be septic or a patient being

treated for an autoimmune disorder who develops new onset paranoia may have a

steroid-induced

psychosis. Secondly, the patient’s physical

capacity to tolerate certain psychiatric medications, such as tricyclic

antidepressants or lithium, must be assessed. Finally, many patients who

present to a psychiatrist have had inadequate medical care and should be

routinely examined to assess their general level of physical health. This is

especially true for patients with chronic mental illness or substance abuse. In

some settings, such as emergency rooms and inpatient wards, the psychiatrist

may want to perform the physical examination; in others, it may be more

appropri-ate to refer the patient to a general practitioner for this purpose.

Genital, rectal and breast examinations can usually be included even for

anxious and paranoid patients, but when they must be postponed, care should be

taken to complete them at a later time. A same-sex chaperone is necessary for

the security of both the patient and the examiner

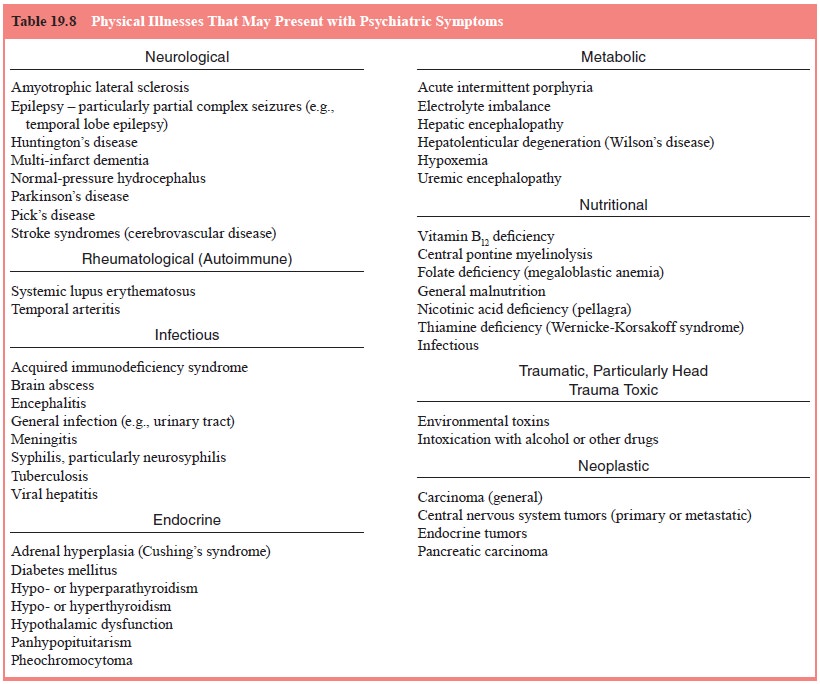

Certain

aspects of the information obtained in the psy-chiatric interview should alert

the psychiatrist to the need for a physical examination. Any indication (Table

19.7) from the his-tory that the psychiatric symptoms followed physical trauma,

in-fection, medical illness, or drug ingestion should prompt a full physical

examination. Similarly, the acute onset of psychiatric symptoms in a previously

psychiatrically healthy individual, as well as symptoms arising at an unusual

age, should raise ques-tions about potential medical causes (Table 19.8).

New-onset psychosis or mania in a previously

healthy 65-year-old is representative of a case requiring pursuit of a medical

condition as the cause because these disorders do not commonly present at this

age. Any gross physical abnormalities, such as gait disturbances, skin lesions,

eye movement abnormalities, lacera-tions, flushed skin, or drooling, should

raise the interviewer’s

suspicion that there might be an underlying medical

condition. Urinary or fecal incontinence is also highly suggestive of a

medi-cal etiology. Stigmata of drug or alcohol use or abuse, such as di-lated

or pinpoint pupils, track marks, evidence of skin popping, or frank evidence of

intoxication (e.g., alcohol on the breath) should also signal the need for a

more thorough physical examination. Abnormalities of speech, such as impaired

fluency or dysarthria, may indicate the presence of an underlying medical

disturbance. Many mood problems may be caused by physical disorders, and even

apparently healthy patients with dysthymia may have hy-pothyroidism that can be

treated medically. Finally, any cognitive disturbances, such as disorientation,

fluctuating level of alert-ness, inattentiveness, or memory problems are, until

proved oth-erwise, evidence of a physical problem that is causing psychiatric

symptoms. In such situations, careful attention should be paid to the patient’s

vital signs, neurological examination (See section on Neurological

Examination), and any indications of infection. In a hospital setting, a

physical examination, including a careful as-sessment of the patient’s vital

signs (including orthostatic meas-urements), cardiovascular status and

pulmonary status precedes the prescription of most psychiatric medications.

Psychiatrists should pay particular attention to a patient’s cardiovascular

status (e.g., electrocardiographic abnormalities, orthostatic hy-potension,

decreased cardiac ejection fraction) before beginning tricyclic

antidepressants, which may induce cardiac conduction disturbances and thus must

be used with caution for patients with such cardiac abnormalities as

arrhythmias or other con-duction abnormalities. Patients taking medications

such as low-potency neuroleptics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic

antidepressants should be assessed for orthostatic hypotension, especially if

they are elderly. If beta-blockers such as propranolol are being considered,

patients should be evaluated for the pres-ence of asthma, which may be

exacerbated by these drugs.

Physical examination may also be warranted during

treat-ment with medication if physical symptoms arise. For example, fever and a

change of mental status during a course of neurolep-tics require a full

physical and neurological examination to rule out neuroleptic malignant

syndrome. Urinary retention induced by medications with anticholinergic side

effects requires an abdominal examination to assess bladder fullness.

Anticholin-ergic-induced constipation may warrant abdominal or rectal

examination to assess for impaction. When patients are seen in office-based

practices, the psychiatrist most often obtains a care-ful medical history and

may complete simple procedures such as blood pressure checks but may refer the

patient to another physi-cian for a complete physical examination.

Related Topics