Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Behavior and Adaptive Functioning

Personality Style

Behavior and Adaptive Functioning

To function adaptively means to behave in such a way that one’s attitudes and actions are well matched to the demands and con-straints of the external environment and that one’s sense of inter-nal discomfort or distress is minimized. Therefore, by definition, the ability to adapt depends both on the individual’s behavioral repertoire and on the external environment. A person’s capacity for adaptive functioning is so crucial that it has been studied in situations ranging from adaptation to long-term missions in outer space (Eksuzian, 1999) to the self-management of life-threaten-ing illnesses such as chronic heart failure (Buetow et al., 2001).

Personality Style

An individual’s personality style has a great

influence on his or her behavior and adaptive functioning. Personality is

shaped from a blend of inborn temperament, genetic strengths and

vulnerabilities, and the impact of positive and negative life experiences.

Psychiatry is moving toward an improved understanding of human behavior that

focuses on the ways that these factors interact with one another.

There is evidence of striking variation among

neonates in their capacity to tolerate frustration, which reflects their inborn

temperaments (Thomas et al., 1963).

Such individual differences in temperament form the biological substrate that

interacts with early development. Temperament affects the degree to which

different infants are susceptible to distress as well as their variations in

attachment style (Rothbart and Ahadi, 1994).

Genetic factors of various types also play a role

in develop-ment, particularly when they interact with environmental factors. In

general, genetic factors account for between 30 and 60% of the variance in

adult personality traits (Carey and DiLalla, 1994).

Life experiences also have an impact on an

individual and affect her or his behavior for better or worse. Considering

whether particular experiences are the result of fate in contrast to whether

they are partially brought about by the person’s own actions can be important

in thinking about their impact and meaning.

While psychiatrists have long suspected links

between early life experiences, especially traumatic ones, and adult

psychopathology, these connections are just now being clearly, empirically

demonstrated. For example, in one recent study, childhood verbal abuse

conferred an increased likelihood of borderline, narcissistic, paranoid,

schizoid and schizotypal per-sonality disorder during adolescence which was

independent of other facts like temperament, physical and sexual abuse, use of

corporal punishment, parental psychopathology and cooccuring psychiatric

disorders (Johnson et al., 2001).

Further, as the rela-tionships between genetic propensities expressed as

temperament or personality factors and environmental influences have been

explicated, some fascinating interactions have emerged. For ex-ample, one

recent study suggested that high levels of the person-ality trait of sensation

seeking, which appears to be genetically mediated, might result in a high

incidence of adverse life events that would in turn help to precipitate

depression (Farmer et al., 2001)

Further, exploration of patterns of disease and personality factors is

beginning to shape genetic investigations by serving as guides for genetic

linkage studies (Nigg and Goldsmith, 1998). For instance, in one study, twins

and siblings who were highly concordant and discordant for neuroticism, a

personality factor, were examined for evidence of anxiety and depression.

Tissue samples were collected to look for areas of genetic overlap and thus to

identify potential foci on chromosomes that warranted further exploration (Kirk

et al., 2000).

Personality styles have been described in a variety

of ways with use of different models of normal personality varia-tion. These

models are either categorical or dimensional in na-ture. In a categorical

model, a person is described as meeting or not meeting the criteria for various

diagnostic categories. In a dimensional model of personality, a person is

evaluated in terms of the blend of various traits or factors he or she

pos-sesses, measured on a continuum. In general, as a person moves toward the

extreme end of a given continuum in the dimensional model, she or he becomes

more likely to meet the criteria for a categorical diagnosis. Some dimensional

models set a threshold beyond which a given characteristic is likely to be a

problem or pathological.

The categorical model is a more common approach to

diag-nosis within clinical psychiatry and within medicine in general. It now

seems clear that useful information is gained from both categorical and

dimensional approaches to examining personal-ity. Thus, although personality

disorders as outlined in the Diag-nostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edi-tion (DSM-IV-TR)

(American Psychiatric Association, 1994) are currently cast in categorical

terms, Oldham and Skodol (2000), among others, have suggested that elements of

both categorical and dimensional systems be included when revisions are made in

DSM-V. Others have proposed a prototype-matching approach to diagnosing

personality disorders in which models of various per-sonality styles are

constructed and psychiatrists make diagnosis by matching their patient to the

best available prototype (Westen and Shedler, 2000).

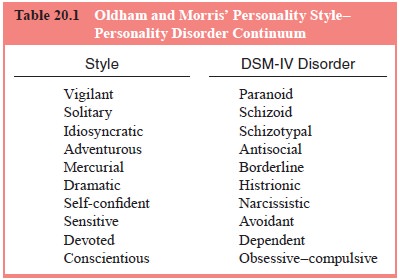

Oldham and Morris (1995) translated each of the

person-ality disorders of the DSM-IV-TR system into a less pathological

collection of categories that describe normal personality styles. In their

system, a cross between a categorical and a dimensional model,

conscientiousness is the positive personality trait that in excess becomes

obsessive–compulsive personality disorder. Table 20.1 summarizes the

personality style–personality disor-der continuum described by Oldham and Morris.

A continuum model such as this one acknowledges

that whereas too much of a good thing may constitute a disorder, everyone’s

personality consists of traits that can be adaptive or maladaptive. The

quantity rather than the quality of a given trait

is often what makes it a problem or adaptive.

Similarly, flexibility and variability are important determinants of a person’s

adaptive capacity.

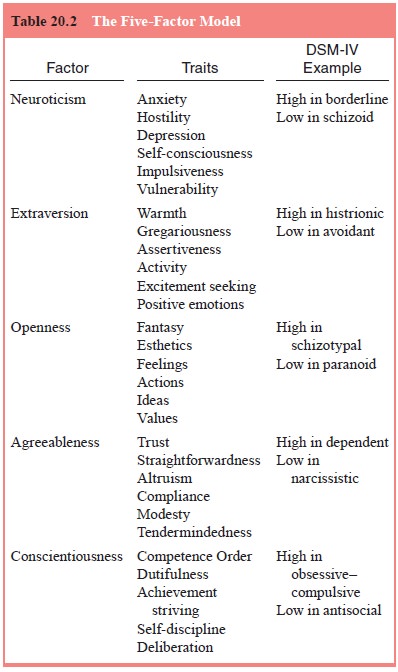

Examples of dimensional models of personality

in-clude the five-factor model (Widiger et

al., 1994), Cloninger’s seven-factor model (Cloninger, 1987; Cloninger et al., 1993), and the biogenic spectrum

model of Siever and Davis (1991). The five-factor model of personality was

first suggested by McDougall (1932) and was elaborated and updated by Dig-man

(1990) and McCrae and Costa (1987) among others. In the five-factor model,

personality traits are described in terms of a taxonomy of five dimensions.

These include neu-roticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness

and conscientiousness. Table 20.2 summarizes the factors of the five-factor

model and their relationship to DSM-IV-TR categories.

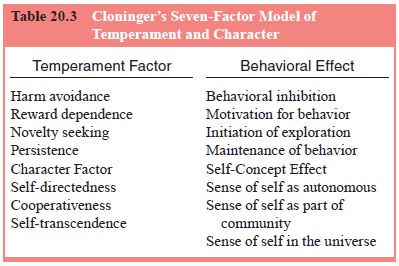

A second dimensional model of personality is

Cloninger’s seven-factor model of temperament and character (Cloninger, 1987;

Cloninger et al., 1993) (Table 20.3).

In this model, a pa-tient’s behavior is evaluated on seven separate dimensions.

Four of the seven dimensions are related to temperament and have been shown to

be independently heritable, manifested early in life, and involved in early perceptual

memory and habit formation

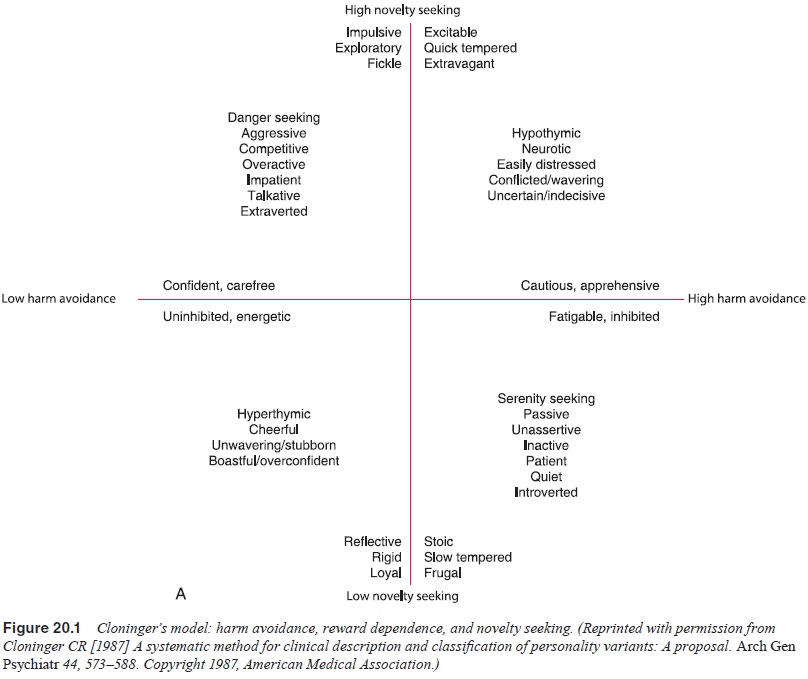

These four dimensions include novelty seeking, harm

avoidance, reward dependence and persistence. Figure 20.1 is a schematic

representation of Cloninger’s model.

Cloninger also describes three dimensions of

character, namely, self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcen-dence.

The blend of these three characteristics that an individual possesses helps to

determine self-concept, such as whether the individual identifies himself or

herself as an autonomous individ-ual, as an integral part of humanity, and as a

part of the universe as a whole. Those with low degrees of self-directedness

and low degrees of cooperativeness are more likely to have personality

disorders (Svrakic et al., 1993).

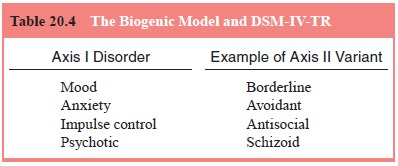

A third dimensional model of personality is the

biogenic spectrum model of Siever and Davis (1991). This model pro-poses that

certain personality styles and disorders are associ-ated with and are

characterological variants of various Axis I disorders. Thus, personality

disorders are not extreme variants of normal but are characterological variants

of Axis I disor-ders. The biogenic spectrum model may be useful in guiding

treatment, such as using anxiolytics to treat avoidant personal-ity disorder

because it is considered to be on a spectrum with Axis I anxiety disorders.

There is growing evidence that the biogenic spectrum model is useful for at

least some Axis I/Axis II disorders. One example is the link between

schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder in which those with the Axis

II disorder demonstrate a better capacity for buffering in certain frontal

brain regions as shown by functional imaging as compared with those with the

full-blown Axis I disorder (Kir-rane and Siever, 2000). Table 20.4 presents details

of the bio-genic model

Related Topics