Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Cervical Neoplasia and Carcinoma

Cervical Carcinoma

CERVICAL CARCINOMA

Between 1950 and 1992, the death

rate from cervical can-cer declined by 74%. The main reason for this steep

decrease is the increasing use of the Pap test for cervical cancer screening.

The death rate continues to decline by approximately 4% per year. Despite the

progress made in early detection and treatment, approximately 11,000 new cases

of invasive cervical carcinoma are diagnosed annually with 3870 deaths.

The average age at diagnosis for

invasive cervical can-cer is approximately 50 years, although the disease may

occur in the very young as well as the very old patient. In studies following

patients with advanced CIN, this precur-sor lesion precedes invasive carcinoma

by approximately 10 years. In some patients, however, this time of progres-sion

may be considerably less.

The etiology of cervical cancer is HPV in more than 90% of the cases. The two major histologic types of inva-sive cervical carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell carcinomas comprise 80% of cases, and adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous car-cinoma comprise approximately 15%. The remaining cases are made up of various rare histologies that behave differ-ently from squamous cell cancer and adenocarcinoma.

Clinical Evaluation

The signs and symptoms of early

cervical carcinoma are variable and nonspecific, including watery vaginal

dis-charge, intermittent spotting, and postcoital bleeding. Often the symptoms

go unrecognized by the patient. Because of the accessibility of the cervix,

accurate diagno-sis often can be made with cytologic screening,

colpo-scopically directed biopsy, or biopsy of a gross or palpable lesion. In

cases of suspected microinvasion and early-stage cervical carcinoma, conization

of the cervix is indi-cated to evaluate the possibility of invasion or to

define the depth and extent of microinvasion. CKC provides the most accurate

evaluation of the margins.

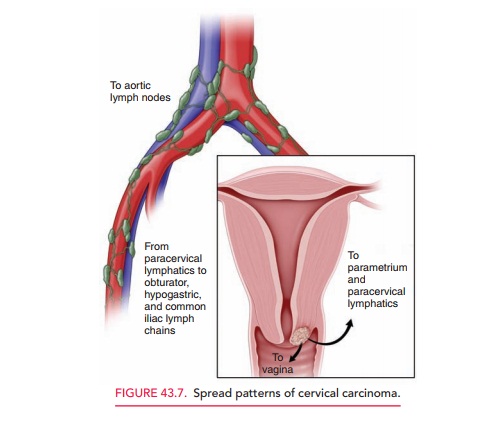

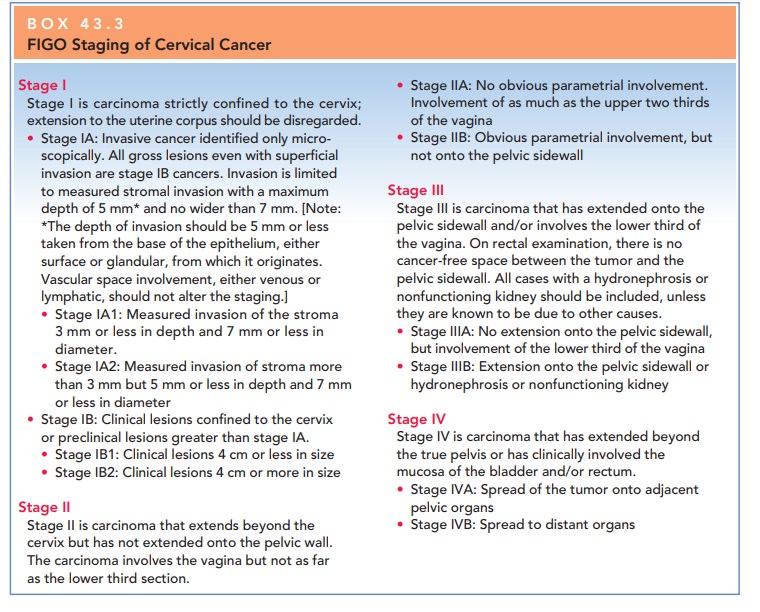

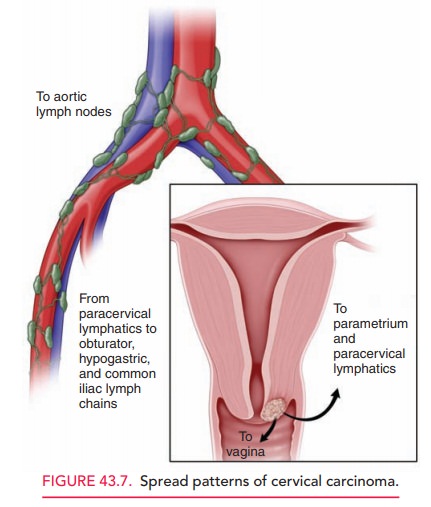

Staging is based on the

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Staging

Classification (Box 43.3). This classification is based both on the histo-logic

assessment of the tumor sample and on physical and laboratory examination to

ascertain the extent of disease. It is useful because of the predictable manner

in which cervical carcinoma spreads by direct invasion and by lym-phatic

metastasis (Fig. 43.7). Careful clinical examination should be performed on all

patients. Examinations should be conducted by experienced examiners, and may be

per-formed under anesthesia. Pretreatment evaluation of women with cervical

carcinoma often can be helpful if provided by an obstetrician–gynecologist with

advanced surgical training, experience, and demonstrated compe-tence, such as a

gynecologic oncologist. Various optional examinations, such as ultrasonography,

computed tomog-raphy (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lym-phangiography,

laparoscopy, and fine-needle aspiration, are valuable for treatment planning

and to help define the extent of tumor growth, especially in patients with

locally advanced disease (i.e., stage IIb or more advanced). Sur-gical findings

provide extremely accurate information about the extent of disease and will

guide treatment plans, but will not change the results of clinical staging.

Management

The clinician should be familiar with the options for treat-ing women with both early and advanced cervical cancer and should facilitate referrals for this treatment. Surgery or radiation therapy may be options for treatment, depending on the stage and size of the lesion:

·

Patients with squamous cell

cancers and those with ade-nocarcinomas should be managed similarly, except for

those with microinvasive disease. Criteria for micro-invasive adenocarcinomas

have not been established.

·

For stage Ia1, microinvasive

squamous carcinoma of the cervix, treatment with conization of the cervix or

sim-ple extrafascial hysterectomy may be considered.

·

Stage Ia2, invasive squamous

carcinoma of the cervix, should be treated with radical hysterectomy with lymph

node dissection or radiation therapy, depending on clin-ical circumstances.

·

Stage Ib1 should be distinguished

from stage Ib2 carci-noma of the cervix, because the distinction predictsnodal

involvement and overall survival and may there-fore affect treatment and

outcome.

· For stage

Ib and selected IIa carcinomas of the cervix, either radical hysterectomy and

lymph node dissection or radiation therapy with cisplatin-based chemotherapy

should be considered. Adjuvant radiation therapy may be required in those

treated surgically, based on pathologic risk factors, especially in those with

stage Ib2 carcinoma.

· Stage IIb

and greater should be treated with external-beam and brachytherapy radiation

and concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Brachytherapy delivers radiation close to the affected organ or structure. Both high- and low-dose brachytherapy are used to treat cervical cancer. The brachytherapy radiation is delivered using special apparatuses known as tandem and ovoid devices placed through the cervix into the uterus and at the apices of the vagina. The external beam radiation is applied primarily along the paths of lymphatic extension of cervical carcinoma in the pelvis.

The structures close to the

cervix, such as the bladder and distal colon, tolerate radiation relatively

well. Radiation therapy doses are calculated by individual-patient needs to

maximize radiation to the tumor sites and potential spread areas, while

minimizing the amount of radiation to adjacent uninvolved tissues.

Complications of radiation therapy include radiation cystitis and proctitis, which

are usually relatively easy to manage. Other more unusual complica-tions

include intestinal or vaginal fistulae, small bowel obstruction, or

difficult-to-manage hemorrhagic proctitis or cystitis. Tissue damage and

fibrosis incurred by radiation therapy progresses over many years, and these

effects may complicate long-term management.

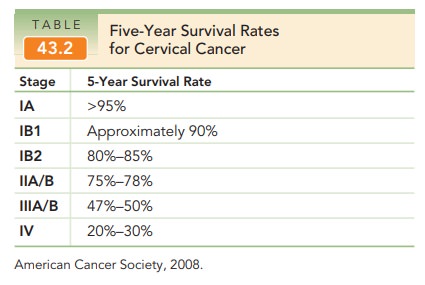

Following treatment for cervical

carcinoma, patients should be monitored regularly, for example, with

thrice-yearly follow-up examinations for the first 2 years and twice-yearly

visits subsequently to year 5, with Pap tests annually and chest x-rays

annually for up to 5 years. The five-year survival rates for cervical cancer

are listed in Table 43.2.

Treatment for recurrent disease is associated with poor cure rates. Most chemotherapeutic protocols have only limited usefulness and are reserved for palliative efforts. Likewise, specific “spot” radiation to areas of recurrence also provides only limited benefit.

Occasional patients with central recurrence (i.e.,

recurrence of disease in the upper vagina or the residual cervix and uterus in

radiation patients) may benefit from ultraradical surgery with partial or total

pelvic exenteration. These candidates are few, but when properly selected, may

benefit from this aggressive therapy.

Related Topics