Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Oral and Esophageal Disorders

Cancer of the Oral Cavity

Cancer of the Oral Cavity

Cancers

of the oral cavity, which can occur in any part of the mouth or throat, are

curable if discovered early. These cancers are associated with the use of

alcohol and tobacco. The combi-nation of alcohol and tobacco seems to have a

synergistic carcinogenic effect. About 95% of cases of oral cancer occur in

people older than 40 years of age, but the incidence is increas-ing in men

younger than age 30 because of the use of smokeless tobacco, especially snuff

(Centers for Disease Control and Pre-vention, 2002).

Cancer

of the oral cavity accounts for less than 2% of all can-cer deaths in the

United States. Men are afflicted more often than women; however, the incidence

of oral cancer in women is increasing, possibly because they use tobacco and

alcohol more frequently than they did in the past. The 5-year survival rate for

cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx is 55% for whites and 33% for African

Americans. Of the 7400 annual deaths from oral cancer, the distribution by site

is estimated as follows: tongue, 1700; mouth, 2000; pharynx, 2100; other, 1600

(American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures, 2002).

Chronic

irritation by a warm pipestem or prolonged exposure to the sun and wind may

predispose a person to lip cancer. Pre-disposing factors for other oral cancers

are exposure to tobacco (including smokeless tobacco), ingestion of alcohol,

dietary defi-ciency, and ingestion of smoked meats.

Pathophysiology

Malignancies

of the oral cavity are usually squamous cell cancers. Any area of the

oropharynx can be a site for malignant growths, but the lips, the lateral

aspects of the tongue, and the floor of the mouth are most commonly affected.

Clinical Manifestations

Many

oral cancers produce few or no symptoms in the early stages. Later, the most

frequent symptom is a painless sore or mass that will not heal. A typical

lesion in oral cancer is a painless indurated (hardened) ulcer with raised

edges. Tissue from any ulcer of the oral cavity that does not heal in 2 weeks

should be ex-amined through biopsy. As the cancer progresses, the patient may

complain of tenderness; difficulty in chewing, swallowing, or speaking;

coughing of blood-tinged sputum; or enlarged cervical lymph nodes.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnostic

evaluation consists of an oral examination as well as an assessment of the

cervical lymph nodes to detect possible metastases. Biopsies are performed on

suspicious lesions (those that have not healed in 2 weeks). High-risk areas

include the buccal mu-cosa and gingiva for people who use snuff or smoke cigars

or pipes. For those who smoke cigarettes and drink alcohol, high-risk areas

include the floor of the mouth, the ventrolateral tongue, and the soft palate

complex (soft palate, anterior and posterior tonsillar area, uvula, and the

area behind the molar and tongue junction).

Medical Management

Management

varies with the nature of the lesion, the preference of the physician, and

patient choice. Surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a

combination of these therapies may be effective.

In

cancer of the lip, small lesions are usually excised liberally; larger lesions

involving more than one third of the lip may be more appropriately treated by

radiation therapy because of su-perior cosmetic results. The choice depends on

the extent of the lesion and what is necessary to cure the patient while

preserving the best appearance. Tumors larger than 4 cm often recur.

Cancer

of the tongue may be treated with radiation therapy and chemotherapy to

preserve organ function and maintain quality of life. A combination of

radioactive interstitial implants (surgical implantation of a radioactive

source into the tissue ad-jacent to or at the tumor site) and external beam

radiation may be used. If the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, the

sur-geon may perform a neck dissection. Surgical treatments leave a less

functional tongue; surgical procedures include hemiglossec-tomy (surgical

removal of half of the tongue) and total glossectomy (removal of the tongue).

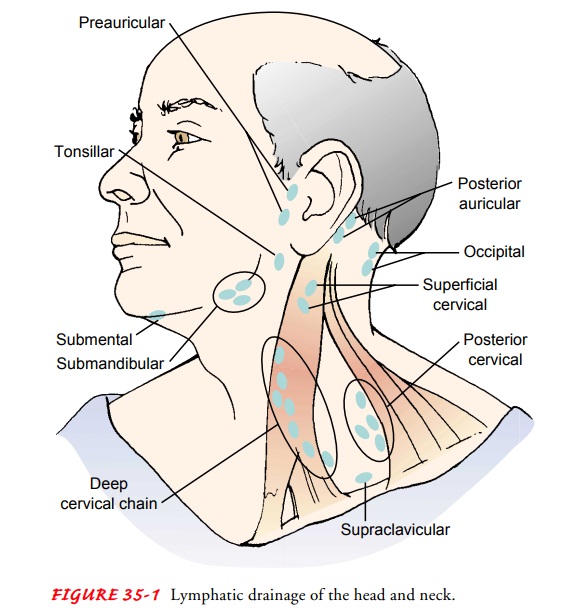

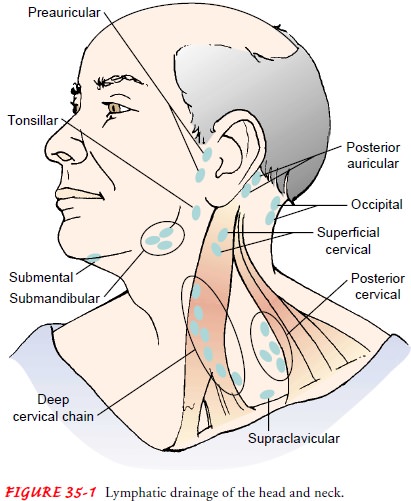

Often cancer of the oral cavity has metastasized through the extensive lymphatic channel in the neck region (Fig. 35-1), re-quiring a neck dissection and reconstructive surgery of the oral cavity. A common reconstructive technique involves use of a radial forearm free flap (a thin layer of skin from the forearm along with the radial artery).

Nursing Management

The

nurse assesses the patient’s nutritional status preoperatively, and a dietary

consultation may be necessary. The patient may re-quire enteral (through the

intestine) or parenteral (intravenous) feedings before and after surgery to

maintain adequate nutrition. If a radial graft is to be performed, an Allen

test on the donor arm must be performed to ensure that the ulnar artery is

patent and can provide blood flow to the hand after removal of the radial

artery. The Allen test is performed by asking the patient to make a fist and

then manually compressing the ulnar artery. The pa-tient is then asked to open

the hand into a relaxed, slightly flexed position. The palm will be pale.

Pressure on the ulnar artery is re-leased. If the ulnar artery is patent, the

palm will flush within about 3 to 5 seconds.

Postoperatively,

the nurse assesses for a patent airway. The pa-tient may be unable to manage

oral secretions, making suction-ing necessary. If grafting was included in the

surgery, suctioning must be performed with care to prevent damage to the graft.

The graft is assessed postoperatively for viability. Although color should be

assessed (white may indicate arterial occlusion, and blue mottling may indicate

venous congestion), it can be difficult to assess the graft by looking into the

mouth. A Doppler ultra-sound device may be used to locate the radial pulse at

the graft site and to assess graft perfusion.

Related Topics