Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper Respiratory Tract Disorders

Cancer of the Larynx

Cancer of the Larynx

Cancer

of the larynx is a malignant tumor in the larynx (voice box). It is potentially

curable if detected early. It represents less than 1% of all cancers and occurs

about four times more fre-quently in men than in women, and most commonly in

persons 50 to 70 years of age. The incidence of laryngeal cancer contin-ues to

decline, but the incidence in women versus men continues to increase. Each year

in the United States, approximately 9,000 new cases are discovered, and 3,700

persons with cancer of the larynx will die (American Cancer Society, 2002).

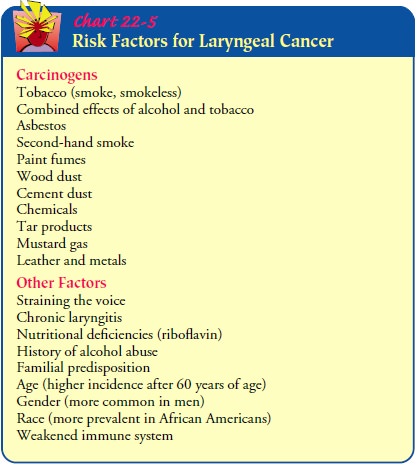

Carcinogens

that have been associated with the development of laryngeal cancer include

tobacco (smoke, smokeless) and alco-hol and their combined effects, exposure to

asbestos, mustard gas, wood dust, cement dust, tar products, leather, and

metals. Other contributing factors include straining the voice, chronic

laryngi-tis, nutritional deficiencies (riboflavin), and family predisposition

(Chart 22-5).

A malignant growth may occur in three different areas of the larynx: the glottic area (vocal cords), supraglottic area (area above the glottis or vocal cords, including epiglottis and false cords), and subglottis (area below the glottis or vocal cords to the cricoid). Two thirds of laryngeal cancers are in the glottic area. Supraglottic cancers account for approximately one third of the cases, sub-glottic tumors for less than 1%. Glottic tumors seldom spread if found early because of the limited lymph vessels found in the vocal cords (Lenhard, Osteen, & Gansler, 2001).

Clinical Manifestations

Hoarseness of more than 2 weeks’ duration is noted early in the patient with cancer in the glottic area because the tumor impedes the action of the vocal cords during speech. The voice may sound harsh, raspy, and lower in pitch. Affected voice sounds are not early signs of subglottic or supraglottic cancer. The patient may complain of a cough or sore throat that does not go away and pain and burning in the throat, especially when consuming hot liquids or citrus juices. A lump may be felt in the neck. Later symptoms include dysphagia, dyspnea (difficulty breathing), unilateral nasal obstruction or discharge, persistent hoarseness, persistent ulcera-tion, and foul breath. Cervical lymph adenopathy, unplanned weight loss, a general debilitated state, and pain radiating to the ear may occur with metastasis.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

An

initial assessment includes a complete history and physical ex-amination of the

head and neck. This will include assessment of risk factors, family history,

and any underlying medical condi-tions. An indirect laryngoscopy, using a

flexible endoscope, is initially performed in the otolaryngologist’s office to

visually eval-uate the pharynx, larynx, and possible tumor. Mobility of the

vocal cords is assessed; if normal movement is limited, the growth may affect muscle,

other tissue, and even the airway. The lymph nodes of the neck and the thyroid

gland are palpated to determine spread of the malignancy (Haskell, 2001).

If

a tumor of the larynx is suspected on an initial examination, a direct

laryngoscopic examination is scheduled. This examina-tion is done under local

or general anesthesia and allows evalua-tion of all areas of the larynx.

Samples of the suspicious tissue are obtained for histologic evaluation. The

tumor may involve any of the three areas of the larynx and may vary in

appearance.

Squamous

cell carcinoma accounts for over 90% of the cases of laryngeal carcinoma

(Haskell, 2001). The staging of the tumor serves as a framework for the

therapeutic regimen. The TNM classification system, developed by the American

Joint Commit-tee on Cancer (AJCC) (Chart 22-6), is the accepted method used to

classify head and neck tumors. The classification of the tumor determines the

suggested treatment modalities. Because many of these lesions are submucosal,

biopsy may require that an incision be made using microlaryngeal techniques or

using a CO2 laser to transect the mucosa and

reach the tumor.

Computed

tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to assess regional

adenopathy and soft tissue and to help stage and determine the extent of a

tumor. MRI is also helpful in post-treatment follow-up in order to detect a

recur-rence. Positron emission tomography (PET scan) may also be used to detect

recurrence of a laryngeal tumor after treatment.

Medical Management

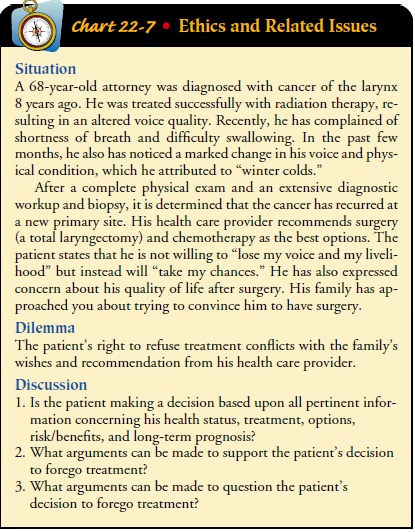

Treatment

of laryngeal cancer depends on the staging of the tumor, which includes the

location, size, and histology of the tumor and the presence and extent of

cervical lymph node in-volvement. Treatment options include surgery, radiation

therapy, and chemotherapy. The prognosis depends on a variety of factors: tumor

stage, the patient’s gender and age, and pathologic features of the tumor,

including the grade and depth of infiltration. The treatment plan also depends

on whether this is an initial diagno-sis or a recurrence. Small glottic tumors,

stage I and II, with no infiltration to the lymph nodes are associated with a

75% to 95% survival rate. Patients with stage III and IV or advanced tumors

have a 50% to 60% survival rate and have a 50% chance of re-currence and a 30%

chance of metastasis. The highest risk of la-ryngeal cancer recurrence is in

the first 2 to 3 years. Recurrence after 5 years is rare and is usually due to

a new primary malig-nancy (Lenhard et al., 2001) (Chart 22-7).

Surgery and radiation therapy are both effective methods in the early stages of cancer of the larynx. Chemotherapy tradition-ally has been used for recurrence or metastatic disease. It has also been used more recently in conjunction with either radiation therapy to avoid a total laryngectomy or preoperatively to shrink a tumor before surgery.

A complete dental examination is per-formed to rule out any oral

disease. Any dental problems are re-solved, if possible, prior to surgery. If surgery

is to be performed, a multidisciplinary team evaluates the needs of the patient

and family to develop a successful plan of care (Forastiere et al., 2001).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Recent

advances in surgical techniques for treating laryngeal can-cer may minimize the

ensuing cosmetic and functional deficits. Depending on the location and staging

of the tumor, four differ-ent types of laryngectomy

(surgical removal of part or all of the larynx and surrounding structures) are

considered:

·

Partial laryngectomy

·

Supraglottic laryngectomy

·

Hemilaryngectomy

·

Total laryngectomy

Some

microlaryngeal surgery can be performed endoscopi-cally. The CO2

laser can be used for the treatment of many laryngeal tumors, with the

exception of large vascular tumors.

Partial Laryngectomy.

A

partial laryngectomy (laryngofissure–thyrotomy) is recommended in the early

stages of cancer in the glottic area when only one vocal cord is involved. The

surgery is associated with a very high cure rate. It may also be performed for

a recurrence when high-dose radiation has failed. A portion of the larynx is

removed, along with one vocal cord and the tumor; all other structures remain.

The airway remains intact and the pa-tient is expected to have no difficulty

swallowing. The voice qual-ity may change or the patient may be hoarse.

Supraglottic Laryngectomy.

A supraglottic laryngectomy is in-dicated in the management of

early (stage I) supraglottic and stage II lesions. The hyoid bone, glottis, and

false cords are re-moved. The true vocal cords, cricoid cartilage, and trachea

remain intact. During surgery, a radical neck dissection is performed on the

involved side. A tracheostomy tube is left in the trachea until the glottic

airway is established. It is usually removed after a few days and the stoma is

allowed to close. Nutri-tion is provided through a nasogastric tube until there

is healing, followed by a semisolid diet. Postoperatively, the patient may

ex-perience some difficulty swallowing for the first 2 weeks. Aspiration is a

potential complication since the patient must learn a new method of swallowing

(supraglottic swallowing). The chief ad-vantage of this surgical procedure is

that it preserves the voice, even though the quality of the voice may change.

Speech therapy is required before and after surgery. The major problem is the

high risk for recurrence of the cancer; therefore, patients are selected

carefully.

Hemilaryngectomy.

A

hemilaryngectomy is performed whenthe tumor extends beyond the vocal cord but

is less than 1 cm in size and is limited to the subglottic area. It may be used

in stage I glottic lesions. In this procedure, the thyroid cartilage of the

lar-ynx is split in the midline of the neck and the portion of the vocal cord

(one true cord and one false cord) is removed with the tumor. The arytenoid

cartilage and half of the thyroid are removed. The patient will have a

tracheostomy tube and nasogastric tube in place for 10 to 14 days following

surgery. The patient is at risk for aspiration postoperatively. Some change may

occur in the voice quality. The voice may be rough, raspy, and hoarse and have

lim-ited projection. The airway and swallowing remain intact.

Total Laryngectomy.

A

total laryngectomy is performed in themost advanced stage IV laryngeal cancer,

when the tumor extends beyond the vocal cords, or for recurrent or persistent

cancer fol-lowing radiation therapy. In a total laryngectomy, the laryngeal

structures are removed, including the hyoid bone, epiglottis, cricoid

cartilage, and two or three rings of the trachea. The tongue, pharyngeal walls,

and trachea are preserved. A total laryngec-tomy will result in permanent loss

of the voice and a change in the airway.

Many

surgeons recommend that a radical neck dissection be performed on the same side

as the lesion even if no lymph nodes are palpable because metastasis to the

cervical lymph nodes is common. Surgery is more difficult when the lesion

involves the midline structures or both vocal cords. With or without neck

dis-section, a total laryngectomy requires a permanent tracheal stoma because

the larynx that provides the protective sphincter is no longer present. The

tracheal stoma prevents the aspiration of food and fluid into the lower

respiratory tract. The patient will have no voice but will have normal swallowing.

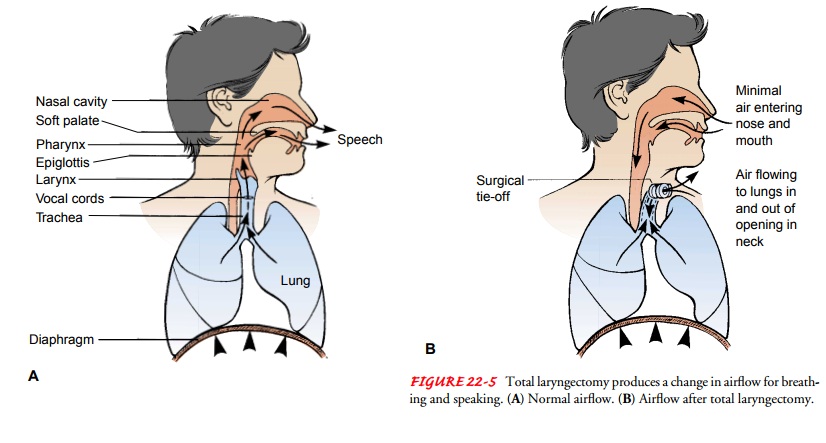

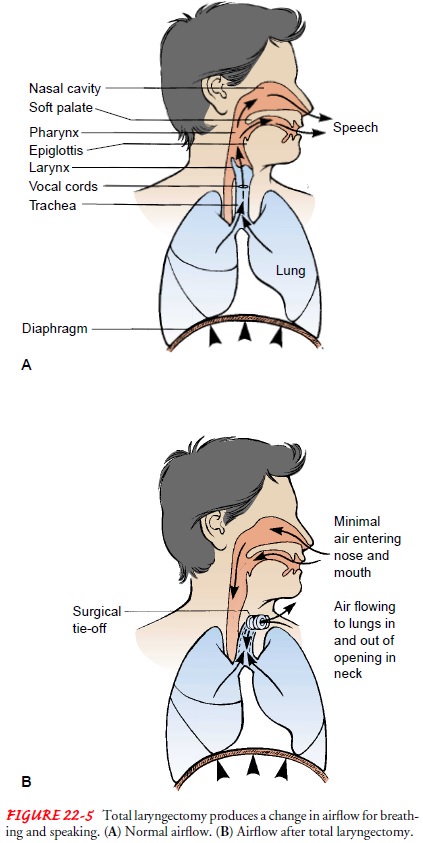

A total laryngectomy changes the manner in which airflow is used for breathing

and speaking, as depicted in Figure 22-5. Complications that may occur include

a salivary leak, wound infection from the develop-ment of a pharyngocutaneous

fistula, stomal stenosis, and dys-phagia secondary to pharyngeal and cervical

esophageal stricture.

RADIATION THERAPY

The

goal of radiation therapy is to eradicate the cancer and pre-serve the function

of the larynx. The decision to use radiation therapy is based on several

factors, including the staging of the tumor (usually used for stage I and stage

II tumors as a standard treatment option) and the patient’s overall health

status, lifestyle (including occupation), and personal preference. Excellent

results have been achieved with radiation therapy in patients with early-stage

(I and II) glottic tumors when only one vocal cord is in-volved and there is

normal mobility (ie, moves with phonation) and in small supraglottic lesions.

One of the benefits of radiation therapy is that patients retain a near-normal

voice. A few may de-velop chondritis (inflammation of the cartilage) or

stenosis; a small number may later require laryngectomy.

Radiation

therapy may also be used preoperatively to reduce the tumor size. Radiation therapy

is combined with surgery in ad-vanced (stages III and IV) laryngeal cancer as

adjunctive therapy to surgery or chemotherapy, and as a palliative measure. A

vari-ety of clinical trials have combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy in

the treatment of advanced laryngeal tumors. Early studies suggest that combined

modality therapy may improve the tumor’s response to radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy com-bined with chemotherapy may be an alternative to a total

laryn-gectomy.

The

complications from radiation therapy are a result of external radiation to the

head and neck area, which may also in-clude the parotid gland responsible for

mucus production. The symptoms may include acute mucositis, ulceration of the

mucous membranes, pain, xerostomia

(dry mouth), loss of taste, dys-phasia, fatigue, and skin reactions. Later

complications may in-clude laryngeal necrosis, edema, and fibrosis.

SPEECH THERAPY

The loss or alteration of speech is discussed with the patient and family before surgery, and the speech therapist conducts a pre-operative evaluation. During this time, the nurse should inform the patient and family about methods of communication that will be available in the immediate postoperative period. These include writing, lip speaking, and communication or word boards. A sys-tem of communication is established with the patient, family, nurse, and physician and implemented consistently after surgery.

A

postoperative communication plan is also developed. The three most common

techniques of alaryngeal communication

are esophageal speech, artificial larynx (electrolarynx), and

tra-cheoesophageal puncture. Training in these techniques begins once medical

clearance is obtained from the physician.

Esophageal Speech.

Esophageal

speech was the primary methodof alaryngeal speech taught to patients until the

1980s. The pa-tient needs the ability to compress air into the esophagus and

expel it, setting off a vibration of the pharyngeal esophageal seg-ment. The

technique can be taught once the patient begins oral feedings, approximately 1

week after surgery. First, the patient learns to

belch and is reminded to do so an hour after eating. Then the technique is

practiced repeatedly. Later, this conscious belching action is transformed into

simple explosions of air from the esophagus for speech purposes. Thereafter,

the speech thera-pist works with the patient in an attempt to make speech

intelli-gible and as close to normal as possible. Because it takes a long time

to become proficient, the success rate is low.

Electric Larynx.

If

esophageal speech is not successful, or untilthe patient masters the technique,

an electric larynx may be used for communication. This battery-powered

apparatus projects sound into the oral cavity. When the mouth forms words

(artic-ulated), the sounds from the electric larynx become audible words. The

voice that is produced sounds mechanical, and some words may be difficult to

distinguish. The advantage is that the patient is able to communicate with relative

ease while working to become proficient at either esophageal or

tracheoesophageal puncture speech.

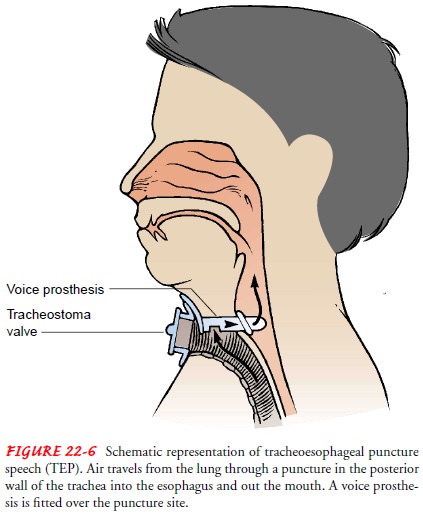

Tracheoesophageal Puncture.

The third technique of alaryngealspeech is tracheoesophageal

puncture (Fig. 22-6). This technique is the most widely used because the speech

associated with it most resembles normal speech (the sound produced is a

combination of esophageal speech and voice), and it is easily learned. A valve

is placed in the tracheal stoma to divert air into the esophagus and out of the

mouth. Once the puncture is surgically created and has healed, a voice

prosthesis (Blom–Singer) is fitted over the punc-ture site. To prevent airway

obstruction, the prosthesis is re-moved and cleaned when mucus builds up. A

speech therapist teaches the patient how to produce sounds. Moving the tongue

and lips to form the sound into words produces speech as before.

Tracheoesophageal speech is successful in 80% to 90% of pa-tients (DeLisa &

Gans, 1998).

Related Topics