Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Upper Respiratory Tract Disorders

Acute Sinusitis - Upper Airway Infections

ACUTE SINUSITIS

The

sinuses, mucus-lined cavities filled with air that drain nor-mally into the

nose, are involved in a high proportion of upper respiratory tract infections.

If their openings into the nasal pas-sages are clear, the infections resolve

promptly. However, if their drainage is obstructed by a deviated septum or by

hypertrophied turbinates, spurs, or nasal polyps or tumors, sinus infection may

persist as a smoldering secondary infection or progress to an acute suppurative

process (causing purulent discharge). Sinusitis

af-fects over 14% of the population and accounts for billions of dol-lars in

direct health care costs (Tierney, McPhee, & Papadakis, 2001). Some

individuals are more prone to sinusitis because of their occupations. For

example, continuous exposure to environ-mental hazards such as paint, sawdust,

and chemicals may result in chronic inflammation of the nasal passages.

Pathophysiology

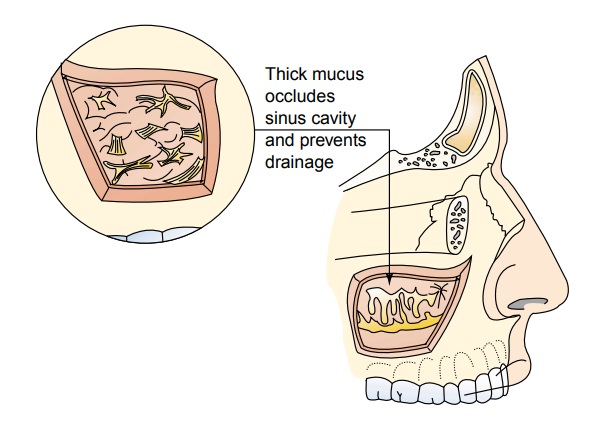

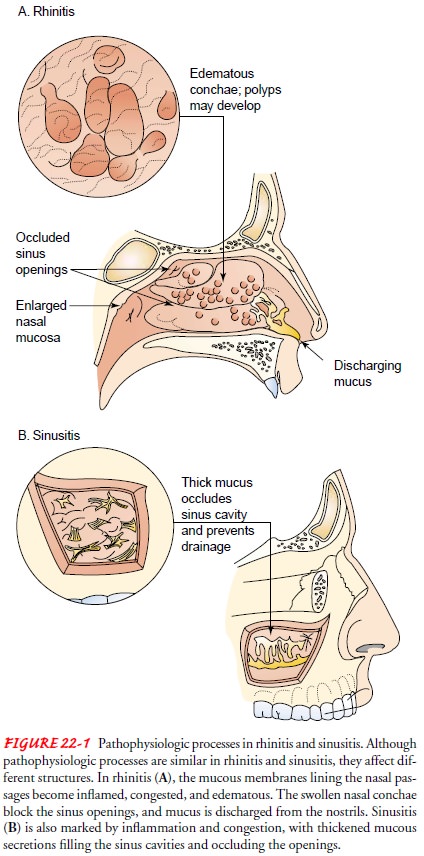

Acute sinusitis is an infection of the

paranasal sinuses. It fre-quently develops as a result of an upper respiratory

infection, such as an unresolved viral or bacterial infection, or an

exacerbation of allergic rhinitis. Nasal congestion, caused by inflammation,

edema, and transudation of fluid, leads to obstruction of the sinus cavi-ties

(see Fig. 22-1). This provides an excellent medium for bac-terial growth.

Bacterial organisms account for more than 60% of the cases of acute sinusitis,

namely Streptococcus pneumoniae,Haemophilus

influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis

(Murray &Nadel, 2001). Dental infections also have been associated with

acute sinusitis.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of acute sinusitis may include facial pain or pressure over the affected sinus area, nasal obstruction, fatigue, purulent nasal discharge, fever, headache, ear pain and fullness, dental pain, cough, a decreased sense of smell, sore throat, eyelid edema, or facial congestion or fullness. Acute sinusitis can be difficult to differentiate from an upper respiratory infection or allergic rhinitis.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

A

careful history and physical examination are performed. The head and neck,

particularly the nose, ears, teeth, sinuses, pharynx, and chest, are examined.

There may be tenderness to palpation over the infected sinus area. The sinuses

are percussed using the index finger, tapping lightly to determine if the

patient experi-ences pain. The affected area is also transilluminated; with

sinusi-tis, there is a decrease in the transmission of light. Sinus x-rays may

be performed to detect sinus opac-ity, mucosal thickening, bone destruction,

and air–fluid levels. Computed tomography scanning of the sinuses is the most

effec-tive diagnostic tool. It is also used to rule out other local or

sys-temic disorders, such as tumor, fistula, and allergy.

Complications

Acute sinusitis, if left untreated, may

lead to severe and occa-sionally life-threatening complications such as

meningitis, brain abscess, ischemic infarction, and osteomyelitis. Other

complications of sinusitis, although uncommon, include severe orbital

cel-lulitis, subperiosteal abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Medical Management

The

goals of treatment of acute sinusitis are to treat the infection, shrink the

nasal mucosa, and relieve pain. There is a growing con-cern over the

inappropriate use of antibiotics for viral upper res-piratory infections; such

overuse has resulted in antibiotics being less effective (more resistant) in

treating bacterial infections such as sinusitis. As a result, careful

consideration is given to the po-tential pathogen before antimicrobial agents

are prescribed.

The

antimicrobial agents of choice for a bacterial infection vary in clinical practice.

First-line antibiotics include amoxicillin (Amoxil),

trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra), and erythromycin. Second-line

antibiotics include cephalosporins such as cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin),

cefpodoxime (Vantin), and cef-prozil (Cefzil) and amoxicillin clavulanate

(Augmentin). Newer and more expensive antibiotics with a broader spectrum

include

.macrolides,

azithromycin (Zithromax), and clarithromycin (Biaxin). Quinolones such as

ciprofloxacin (Cipro), levofloxacin (Levaquin) (used with severe penicillin

allergy), and sparfloxacin (Zagam) have also been used. The course of treatment

is usually 10 to 14 days. A recent report found little difference in clinical

outcomes between first-line and second-line antibiotics; however, costs were greater

when newer second-line antibiotics were used (Piccirillo, Mager, Frisse et al.,

2001).

Use

of oral and topical decongestant agents may decrease mu-cosal swelling of nasal

polyps, thereby improving drainage of the sinuses. Heated mist and saline irrigation

also may be effective for opening blocked passages. Decongestant agents such as

pseudo-ephedrine (Sudafed, Dimetapp) have proven effective because of their

vasoconstrictive properties. Topical decongestant agents such as oxymetazoline

(Afrin) may be used for up to 72 hours. It is important to administer them with

the patient’s head tilted back to promote maximal dispersion of the medication.

Guaife-nesin (Robitussin, Anti-Tuss), a mucolytic agent, may also be ef-fective

in reducing nasal congestion.

In

2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a public health advisory

concerning phenylpropanolamine, which previously had been commonly used in oral

decongestants and diet pills. The voluntary recall of products containing this

ingre-dient was based on a study linking its use with hemorrhagic stroke in

women. Men may also be at risk (Kernan et al., 2000).

Antihistamines

such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), ceti-rizine (Zyrtec), and fexofenadine

(Allegra) may be used if an al-lergic component is suspected. If the patient

continues to have symptoms after 7 to 10 days, the sinuses may need to be

irrigated and hospitalization may be required.

Nursing Management

TEACHING PATIENTS SELF-CARE

Patient

teaching is an important aspect of nursing care for the pa-tient with acute

sinusitis. The nurse instructs the patient about methods to promote drainage

such as inhaling steam (steam bath, hot shower, and facial sauna), increasing

fluid intake, and apply-ing local heat (hot wet packs). The nurse also informs

the patient about the side effects of nasal sprays and about rebound

conges-tion. In the case of rebound congestion, the body’s receptors, which

have become dependent on the decongestant sprays to keep the nasal passages

open, close and congestion results after the spray is discontinued.

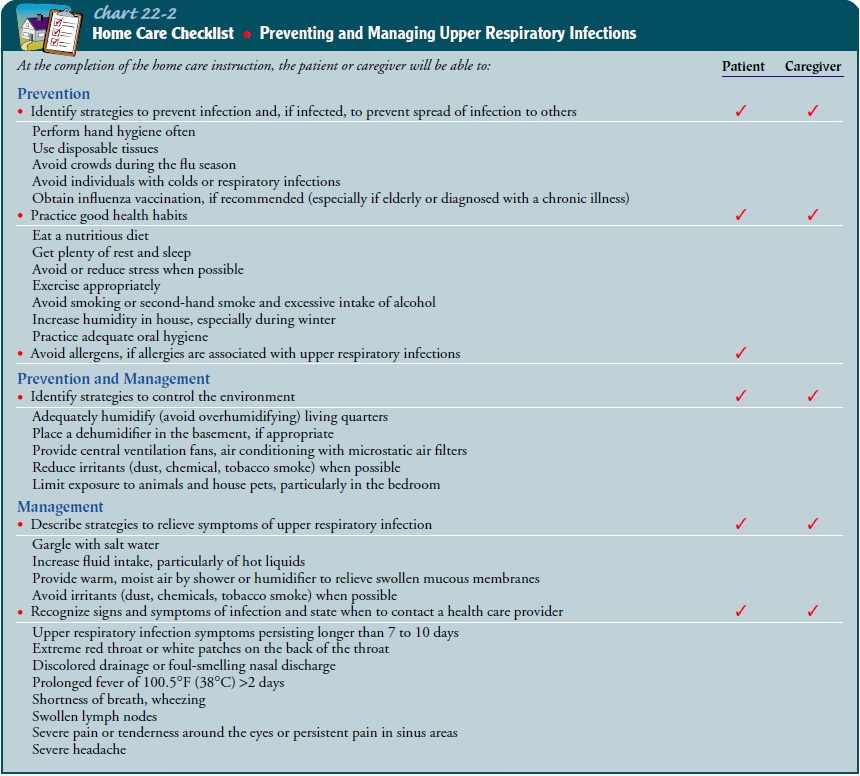

The

nurse stresses the importance of following the recom-mended antibiotic regimen,

because a consistent blood level of the medication is critical to treat the

infection. The nurse teaches the patient the early signs of a sinus infection

and recommends pre-ventive measures such as following healthy practices and

avoiding contact with people who have upper respiratory infections (see Chart

22-2).

The

nurse should explain to the patient that fever, severe headache, and nuchal

rigidity are signs of potential complica-tions. If fever persists despite

antibiotic therapy, the patient should seek additional care.

Related Topics