Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Sleep and Sleep-Wake Disorders

Breathing-related Sleep Disorder

Breathing-related

Sleep Disorder

The

essential feature of this disorder is sleep disruption result-ing from sleep

apnea or alveolar hypoventilation, leading to com-plaints of insomnia or, more

commonly, excessive sleepiness. The disorder is not accounted for by other

medical or psychiatric disorders or by medications or other substances.

Diagnosis

The major

diagnostic criterion for sleep apnea is cessation of breathing lasting at least

10 seconds and an apnea index (number of apneic events per hour of sleep) of

five or more. Most apneic episodes are terminated by transient arousals.

Hypopneas (50% decrease in respiration) may also produce arousal or hypoxia

even when complete apneas do not occur. Therefore, rather than just the apnea

index, a respiratory disturbance index (number of respira-tory events, or

number of apneas plus hypopneas per hour of sleep) is used. Whereas the

criterion for the respiratory disturbance in-dex has not been fully

established, many psychiatrists use a respi-ratory disturbance index of 10 or

greater for purposes of diagnosis. Each time respiration ceases, the individual

must awaken to start breathing again. Once the person goes back to sleep,

breathing stops again. This pattern continues throughout the night.

Clini-cally, however, it is not unusual to see patients who stop breathing for

60 to 120 seconds with each event and experience hundreds of events per night.

Many individuals with BRSD cannot sleep and breathe at the same time and

therefore spend most of the night not breathing and not sleeping. In contrast,

the central alveolar hypoventilation syndrome is not associated with either

apneas or hypopneas, but impaired ventilatory control or hypoventilation

re-sults in hypoxemia. It is most common in morbid obesity.

Sleep apnea is characterized by repetitive episodes of upper airway obstruction that occur during sleep, resulting in numer-ous interruptions of sleep continuity, hypoxemia, hypercapnia, bradytachycardia, and pulmonary and systemic hypertension. It may be associated with snoring, morning headaches, dry mouth on awakening, excessive movements during the night, falling out of bed, enuresis, cognitive decline and personality changes, and complaints of either insomnia or, more frequently, hypersomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness. The typical patient with clini-cal sleep apnea is a middle-aged man who is overweight or who has anatomical conditions narrowing his upper airway.

There are three types of apnea. The first is

obstructive sleep apnea, which involves the collapse of the pharyngeal airway

during inspiration, with partial or complete blockage of airflow. The person

still attempts to breathe, and one can observe the diaphragm moving, but the

airway is blocked and therefore there is no air exchange. It can be caused by

baggi-ness or excessive pharyngeal mucosa and a large uvula, fatty infiltration

at the base of the tongue, or collapse of the pharyn-geal walls. The resulting

decreased air passage compromises alveolar ventilation and causes blood-oxygen

desaturation and strenuous attempts at inspiration through the narrowed airway,

all of which lighten and disrupt sleep. Hypercapnia, which re-sults either from

obstructive sleep apnea or from lung disease, reduces breathing without the

presence of disruptive inspira-tory efforts.

The

second type is central sleep apnea, which results from failure of the respiratory

neurons to activate the phrenic and inter-costal motor neurons that mediate

respiratory movements. There is no attempt to breathe, and although the airway

is not collapsed, there is no respiration. This type of apnea is more commonly

as-sociated with heart disease. The third type is mixed sleep apnea, which is a

combination, generally beginning with a central com-ponent and ending with an

obstructive component.

The

lifetime prevalence of BRSD in adults has been esti-mated to be 9% in men and

4% in women. The prevalence does increase with age, particularly in

postmenopausal women. The prevalence in the elderly has been estimated to be

28% in men and 19% in women.

During

apneas and hypopneas, the blood-oxygen level often drops to precarious levels.

In addition, one often sees car-diac arrhythmias and nocturnal hypertension in

association with the respiratory disturbances. The cardiac arrhythmias include

bradycardia during the events and tachycardia after the end of the events. It

is not unusual to see premature ventricular contractions, trigeminy and

bigeminy, asystole, second-degree atrioventricular block, atrial tachycardia,

sinus bradycardia and ventricular tach-ycardia. However, the electrocardiogram

taken during the wak-ing state might be normal. It is only during the

respiratory events during sleep that the abnormalities appear

BRSD,

especially central sleep apnea, is commonly seen in patients with congestive

heart failure. Cor pulmonale may also be a consequence of longstanding BRSD and

is seen in both sleep apnea syndrome and primary hypoventilation. Patients may

present with unexplained respiratory failure, polycythemia, right ventricular

failure and nocturnal hypertension. About 50% of patients with BRSD have

hypertension, and about one-third of all hypertensive patients have BRSD. In

the large cross-sectional study, it was found that both systolic and diastolic

blood pressure (SDB) as well as the prevalence of hypertension increased

signifi-cantly with increasing SDB (Nieto et

al., 2000). It has also been shown that there is a dose–response

association between SDB at baseline and hypertension 4 years later suggesting

that SDB may be a risk factor for hypertension and consequent cardiovascular

morbidity.

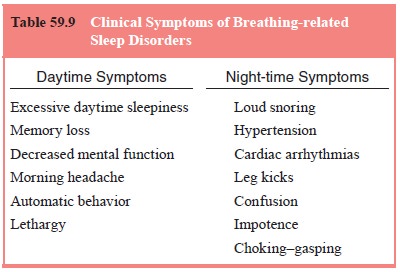

The most

common symptoms of BRSD include excessive daytime sleepiness and snoring. The

excessive daytime sleepi-ness probably results from sleep fragmentation caused

by the fre-quent nocturnal arousals occurring at the end of the apneas and

possibly from hypoxemia. The excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with

lethargy, poor concentration, decreased motiva-tion and performance, and

inappropriate and inadvertent attacks of sleep. Sometimes the patients do not

realize they have fallen asleep until they awaken.

The

second complaint is loud snoring, sometimes noisy enough to be heard throughout

or even outside the house. Of-ten the wife has complained for years about the

snoring and has threatened to sleep elsewhere if she has not moved out already.

Bed partners describe a characteristic pattern of loud snoring interrupted by

periods of silence, which are then terminated by snorting sounds. Snoring

results from a partial narrowing of the airway caused by multiple factors, such

as inadequate muscle tone, large tonsils and adenoids, long soft palate,

flaccid tissue, acromegaly, hypothyroidism, or congenital narrowing of the oral

pharynx. Snoring has been implicated not only in sleep ap-nea but also in

angina pectoris, stroke, ischemic heart disease and cerebral infarction, even

in the absence of complete sleep apneas. Because the prevalence of snoring

increases with age, especially in women, and because snoring can have serious

medi-cal consequences, the psychiatrist must give serious attention to

complaints of loud snoring. Snoring is not always a symptom of BRSD.

Approximately 25% of men and 15% of women are ha-bitual snorers.

Patients

with BRSD are frequently overweight. In some patients, a weight gain of 20 to

30 lb might bring on episodes of BRSD. The same fatty tissue seen on the

outside is also present on the inside, making the airway even more narrow.

Because obstructive sleep apnea is always caused by the collapse of the airway,

in patients of normal weight, anatomical abnormalities (such as large tonsils,

long uvula) must be considered.

Other

symptoms of BRSD include unexplained morning headaches, nocturnal confusion,

automatic behavior, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, or night

sweats. The severity of BRSD will depend on the severity of the cardiac

arrhythmias, hypertension, excessive daytime sleepiness, respiratory

distur-bance index, amount of sleep fragmentation and amount of oxy-gen

desaturation.

Mild to moderate sleep-related breathing

disturbances in-crease with age, even in elderly subjects without major

complaints about their sleep. The frequency is higher in men than in women, at

least until the age of menopause, after which the rate in women increases and

may approach that of men. With use of the apnea index of five or more apneic

episodes per hour as a cutoff crite-rion, prevalence rates range from 27 to 75%

for older men and from 0 to 32% for older women. In general, the severity of

apnea in these older persons is mild (an average apnea index of about 13) compared

with that seen in patients with clinical sleep ap-nea. However, older men and

women with mild apnea have been reported to fall asleep at inappropriate times

significantly more often than older persons without apnea. Furthermore, the

fre-quency of sleep apnea and other BRSDs is higher in individuals with hypertension,

congestive heart failure, obesity, dementia and other medical conditions.

Increased

mortality rates have been noted in excessively long sleepers, therefore sleep

apnea may account for some of these excess deaths. This is also consistent with

evidence that excess deaths from all causes increase between 2 and 8 AM,

specifically deaths related to ischemic heart disease in patients older than 65

years. There have been several studies suggest-ing that untreated sleep apnea

in the elderly may lead to shorter survival.

The

clinical significance of relatively mild “subclinical” sleep apneas is not

fully understood yet. Psychiatrists should be aware, however, that such

disturbances might be associated with either insomnia or excessive daytime

sleepiness. Furthermore, for some patients with sleep apnea, administration of

hypnotics, alcohol, or other sedating medications is relatively

contraindi-cated. The risk is not yet known, but reports indicate that

benzo-diazepines as well as alcohol may increase the severity of mild sleep

apnea. Therefore, psychiatrists should inquire about snor-ing, gasping, and

other signs and symptoms of sleep apnea before administering a sleeping pill.

If patients have excessive sleepi-ness or morning hangover effects while taking

benzodiazepines, major tranquilizers, or other sedating medications, the

psychia-trist should consider the possibility of an iatrogenic BRSD due to

medications.

The

diagnosis of BRSD must be differentiated from other disorders of excessive

sleepiness such as narcolepsy (Table 59.9). Patients with BRSD will not have

cataplexy, sleep-onset paraly-sis, or sleep-onset hallucination. Narcolepsy is

not usually as-sociated with loud snoring or sleep apneas. In laboratory

record-ings, patients with BRSD do not usually have sleep-onset REM periods

either at night or in multiple naps on the Multiple Sleep Latency Test.

However, one must be aware that both BRSD and narcolepsy can be found in the

same patient. BRSD must also be distinguished from other hypersomnias, such as

those related to major depressive disorder or circadian rhythm disturbances.

Treatment of Sleep Apnea

Sleep

apnea is sometimes alleviated by weight loss, avoidance of sedatives, use of

tongue-retaining devices and breathing air under positive pressure through a

face mask (continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP]). Oxygen breathed at

night may alleviate insomnia associated with apnea that is not accompanied by

im-peded inspiration. Surgery may be helpful, for example, to cor-rect enlarged

tonsils, a long uvula, a short mandible, or morbid obesity. Pharyngoplasty,

which tightens the pharyngeal mucosa and may also reduce the size of the uvula,

or the use of a cervical collar to extend the neck, may relieve heavy snoring. Although

tricyclic antidepressants are sometimes used in the treatment of clinical sleep

apnea in young adults, they may cause considerable toxic effects in older

people. The newer shorter-acting nonbenzo-diazepine hypnotics seem to be safer

in these patients and may be considered in those patients who snore.

Related Topics