Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: The Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorders: Treatment

Treatment

Nonpharmacological and Behavioral Treatments

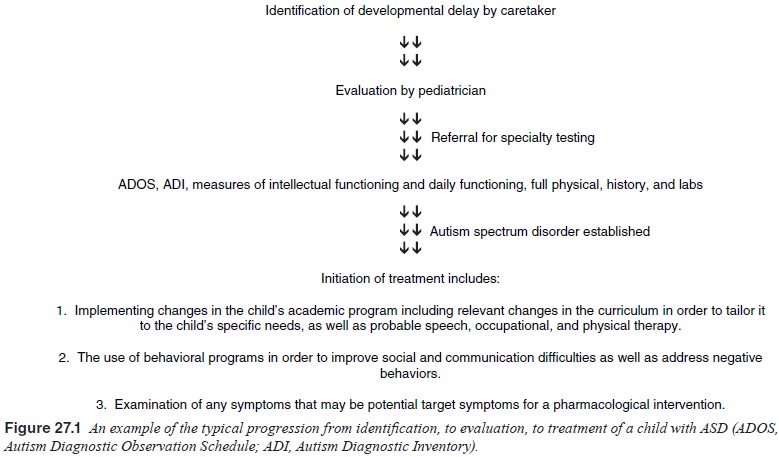

Developing a comprehensive individual intervention

program for a child with ASD is a daunting task for the child’s parents (Figure

27.1). Each child is unique, with a different set of diffi-culties, as well as

strengths. The child’s primary physician must work with the parents to help

make this task less overwhelming. The physician can anticipate being asked

about a wide array of al-ternative treatments being offered in the community,

which vary enormously in their claims, in the integrity of those making the

claims, and in their ultimate safety and utility.

The physician who immediately and outright and pejoratively dismisses these

alterna-tives as useless is not helpful to the child or his family (the

excep-tion being dangerous or cost-prohibitive prospective treatments). Rather,

it is helpful to listen and then educate the family, at a level commensurate

with their sophistication, about how to analyze and interpret claims and

science underlying these treatments.

Autistic disorder is recognized as a chronic

disorder with a changing course requiring a long-term course of treatment that

includes the necessity of an intervention with various treatments at different

times. At the present time, most treatments for the ASDs are symptom directed.

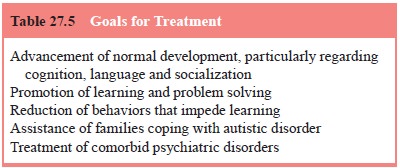

Given that there is no current cure for autistic disorder or the other ASD,

goals of treatment should encompass short-term and long-term needs of the

individual and his or her family (Table 27.5).

Every attempt should be made to achieve treatment

goals on a community-based environment since institutionalization may hinder a

child’s ability to learn means of functioning and adapting in typical social

settings. Community-based treatment can usually be maintained, except in times

of extreme stress or need, during which time a child (and family) might benefit

from respite care or brief hospitalization. Effective treatment often entails

setting appropriate expectations for the child and adjust-ing the child’s

environment to foster success.

Approach to Treatment

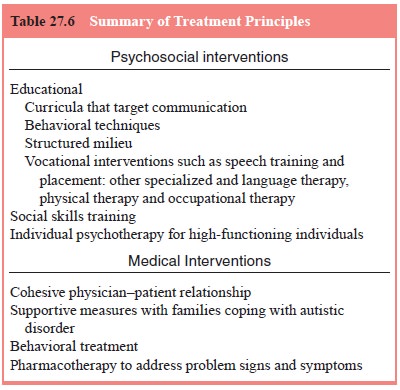

Because the autistic individual often requires

diverse treatments and services simultaneously, the role of the primary

physician is to be the coordinator of services. Frequent visits with the child

and the child’s caretakers initially allow the physician to assess the

in-dividual needs of the child while establishing a therapeutic alli-ance. An

effective approach often calls for the services of a number of professionals

working in a multidisciplinary fashion. This group may include psychiatrists,

pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, psychologists, special educators, speech

and language therapists social workers, and other specialized therapists (Table

27.6)

There is significant controversy over what

particular forms of therapy are best for children with ASD. Some of this

contro-versy is a result of claims of children making dramatic improve-ments

with some of these therapies.

The most successful interventions use a variety of

posi-tive reinforcement schedules to enhance the desired behaviors and

extinguish undesirable behaviors. Discrete trial training, an operant

conditioning model, is particularly useful in this regard. Generalization of

skills from the behavioral training environment to other settings is a key to

success. Applied behavioral analysis (ABA) uses careful assessment of adaptive

and maladaptive be-haviors and specific interventions addressing each behavior

and children receiving ABA have shown significant improvement in a number of

areas, including IQ, visual–spatial skills, language, and academics (Smith et al. 2001).

Problem Behaviors

A prerequisite to putting a behavioral plan in

place with a child with ASD is to identify the problem behaviors. These

behaviors often include interfering repetitive actions, self-injurious

behav-iors, or aggression. While there is little difficulty in identifying

these highly visible behaviors, what is much more difficult is 1) determining

the antecedents to these behaviors and 2) knowing what constitutes an

appropriate reaction or consequence to these behaviors on the part of the

caregiver.

To determine the antecedent is often

extraordinarily difficult, since it is often not apparent exactly what happened

in the environment that stimulated the behavior. This is particularly true if

the behavior is chronic and has developed some autonomous function (i.e., no

longer a stimulus–response event). To make things more complicated, it could be

internal perception or meaning of what happened in a child with autism (poor

language and socially nonresponsive) that may have initiated the behavior. For

example, imagine a nonverbal child frustrated by his inability to continue a

mental routine created by a teacher insisting that the child orient himself to

a school task like sitting in reading circle. Further, assume that the child

does not have a repertoire of appropriate social responses, and instead

responds by biting the teacher on the arm. It will be very difficult for the

teacher to know that the child was in the middle of a mental routine and not

able to communicate his distress verbally, thus leading to the inappropriate

behavior. It takes time and attention to understand these events processes in

children with ASD. Once they are clear, appropriate behavioral intervention is

possible.

Durand and Carr (1991) attempted to determine the

func-tion of problem behaviors in children with ASD. They concluded that most

behaviors could be classified as:

1. a need for help;

2. a desire to escape a stressful situation;

3. a desire to obtain an object;

4. an attempt to protest unwanted events;

5. an attempt to obtain stimulation or attention.

Obsessions and Rituals

Children with ASD often engage in rituals and

routines which appear to be an attempt to relieve anxiety and/or to exert

control over their environment. The key to success is a gradual shap-ing of the

behavior rather than dramatic expectations and harsh consequences. One should

begin intervention by evaluating pos-sible, underlying stimuli or predisposing

factors for the behavior. Strategies include determining when, where and for

how long an activity can take place. Additional strategies include making

environmental changes that reduce anxiety and even ignoring behaviors that do

not create undue problems. Adjunct pharmaco-logical intervention is often

helpful.

Communication Therapy

Up to 50% of children with ASD will not acquire

useful language. For those with some but not fully intact language skills,

speech therapy is an important part of therapeutic and academic plan-ning. An

emphasis on the social use of language is often helpful, and when the child can

articulate some of his or her needs, there is often a reduction in problem

behaviors.

Longitudinal studies indicate that children who

have not acquired useful language by the age of 7 usually have longstanding

verbal communication difficulties. For these children, it is often helpful to

devise an alternative means of communication: sign language or use of

augmentative communication devices such as computers and picture exchange

communication systems or PECS. PECS involves the use of photographs or line

drawings on cards. The child then points to or hands the appropriate card or

cards to another person in order to effect communication. Once again, children

are encouraged to use verbalization, when possible, in conjunction with sharing

the cards (Erdmann et al., 1996).

Irrespective of the technique used, establishing a consistent method of communication is central to the treatment of

individuals with ASD.

Social Interaction Therapy

Children and adults with ASD lack many of the

innate and learned social skills, especially reciprocal social interactions,

that most people simply take for granted. Maintaining appropri-ate

interpersonal distance, spontaneously initiating conversation, participating in

reciprocal social exchange and other facets of complex social interaction are

not easily incorporated in the rou-tine behaviors and activities of individuals

with ASDs. Subtlety and changing complexity of social interaction as well as

the in-nateness of many social skills is a central part of daily life and a key

to successful adaptation for typically functioning individu-als. Helping

individuals with ASDs address these challenges is difficult but also critical

for enhancing overall functioning.

Odom and Strain (1986) identified the three primary

techniques that can be effectively utilized:

· Proximity.

Establish proximity refers to the fact that it is very helpful to have the

child with ASD near other children in the en-vironment. The mere proximity

increases the likelihood of in-teraction and imitation as well as positive

social reinforcement.

·

Use. The use of prompts relates to have specific

prompts and reinforcement cues to use previously learned behaviors in so-cial

settings (e.g., “Raise your hand if you have a question”). Attention to

reinforcement means that even a less than fully competent attempt at

appropriate social behavior, even if re-sponse to a prompt, receive clear and

effective reinforcement when it occurs (e.g., calling on the child promptly

when he raises his hand to ask a question and also saying “You did a good job

when you raised your hand to ask the question”).

· Encourage

peer initiation is helpful to train peers who are likely to interact with the

child or adult with ASD in tech-niques for initiating social contact. For many

individuals, this means explaining the disability and dealing with fears or

bi-ases. For others, it may mean encouraging them to persist in their attempts

at engagement, even in the face of limited, inap-propriate, or inadequate

responses.

Academic Needs

Academic resources and placement are important

components in the child’s overall treatment. First and foremost, schools are

where children go to acquire social skills and acquaintances, as well as

academic skills. Secondly, schools often have a variety of skilled

professionals who are trained to provide necessary serv-ices for the individual

with ASD. And, finally, in the USA, all public schools have a statutory

obligation to provide all children (even those with disabilities) with a free

and appropriate educa-tion in the least restrictive environment.

Previously, children with ASD had been put in

alternative settings, but more recently there has been increased interest in

maintaining many ASD children in regular classroom settings. Studies seem to

indicate that ASD children in regular classrooms have increased social

interaction, a larger social network and have more advanced individualized

education plan goals later in their academic careers (Fryxell and Kennedy,

1995). Whether a child is fully or partially included in a regular classroom or

placed in a self-contained setting, each ASD child will need to have an indi-vidualized

plan of care that carefully and specifically articulates goals and the

techniques to be used to reach those goals. In addi-tion, specific measures of

goal attainment and regular review of the plan should be a part of this

important intervention. In order to establish these goals and plans, a full

assessment of the child’s strengths and weaknesses must be completed through

the efforts of numerous skilled professionals. Educational plans must

incor-porate academic, social and behavioral goals.

Pharmacotherapy

At this time, there are no pharmacological agents

with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved labeling specific for the

treatment of ASD in either children or adults. Many of the symptoms commonly

seen in ASD (rituals, aggressive behavior and hyperactivity) are also commonly

seen in children, adoles-cents and adults with mental retardation but without a

PDD. Some of the pharmacological strategies for the treatment of autistic

dis-order have been extrapolated from studies of related conditions, largely in

adults, but including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and OCD.

Clinicians and families should be reminded before any treatment is initiated

that:

• Current treatments target symptoms.

• Current treatments do not target a specifi c

etiological mechanism for ASD.

• Anecdotal reports do not establish effi cacy,

effectiveness, or safety for any treatment.

• Controlled, double-blind trials (preferably with

replication) are the contemporary standard for determining if a treatment is

safe and appropriate.

• All treatments have side effects.

Before specific pharmacological agents are

discussed, it must be stressed that one should not use psychopharmacological

agents with the expectation that they will cure children with autistic disor-der

as many parents and teachers of children with autistic disorder expect

medication to eliminate core social, cognitive and commu-nication dysfunction.

There is no pharmacological substitute for appropriate educational, behavioral,

psychotherapeutic, vocational and recreational programming. It is essential to

remember and to remind parents, teachers and others that medication should

always be seen as an adjunct to these core interventions that address the

developmental challenges associated with these disorders.

Because many individuals with ASD have impairments

in language and social communication, the use of rating scales be-comes an

essential part of the treatment. Standard rating scales provide the

pharmacotherapist with a framework in which to assess response to medication

and a relatively straightforward way to collect standard information about the

patient’s function-ing in a variety of settings. The Aberrant Behavior

Checklist – Community Version (Aman, 1994) covers many target symptom areas for

most patients with ASD. Although rating scales cannot replace careful clinical

examination of the patient and interviews with parents and teachers, they may

be graphed next to dosages of medications to assist in treatment planning in

response to the patient’s clinical condition. This is often not only helpful in

mak-ing clinical decisions but also gives families and service provid-ers a

concrete sense of how a treatment is progressing.

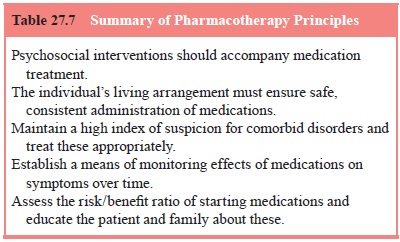

The use of medications to treat autistic disorder

and other ASDs appears to have significant potential as an adjunct to

edu-cational, environmental and social interventions. It is a reason-able goal

for the pharmacotherapist to adopt the judicious use of psychopharmacological

agents to assist in alleviating symptoms that have been found to respond to

pharmacological intervention (Table 27.7). This focus on facilitating

adaptation requires atten-tion to five important principles:

·

Environmental manipulations, including behavioral

treat-ment, may be as effective as, if not more effective than, medi-cation for

selected symptomatic treatment.

·

It is essential that the living arrangement for the

individual must ensure safe and consistent administration and monitor-ing of

the medication to be used.

·

Individuals with autistic disorder and other ASDs

often have other DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders. If a comorbid DSM-IV-TR Axis I

disorder is present, standard treatment for that disorder should be initiated

first.

· Medication should be selected on the basis of potential effects on target symptoms and there should be an established way of specifically monitoring the response to the treatment over time.

· A careful

assessment of the risk/benefit ratio must be made before initiating treatment

and, to the extent possible, the pa-tient’s caretakers and the patient must

understand the risks and benefits of the treatment.

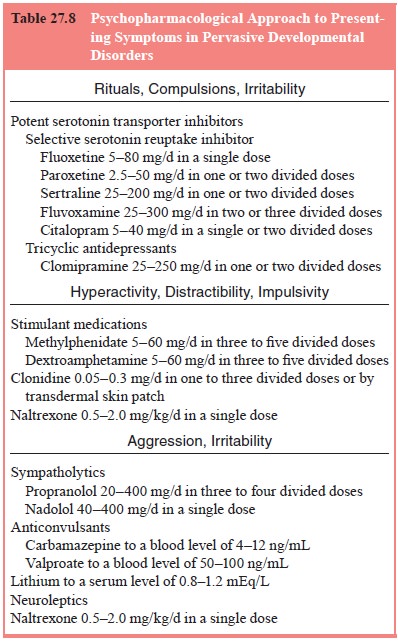

Potent Serotonin Transporter Inhibitors

This class of agents includes selective serotonin

reuptake inhibi-tors (SSRIs) as well as the less selective but potent clomipramine,

a tricyclic antidepressant (Table 27.8). This group of medications is most

effective when insistence on routines or rituals are present to the point of

manifest anxiety or aggression in response to interrup-tion of the routines or

rituals, or after the onset of another disorder such as major depressive

disorder or OCD. The common side effects associated with SSRIs are motor

restlessness, insomnia, elation, ir-ritability and decreased appetite. Because

many of these symptoms may be present in the often cyclical natural course of

ASD before the medication is initiated, the emergence of new symptoms, a

dif-ferent quality of the symptoms, and occurrence of these symptoms in a new

cluster are clues that the symptoms are side effects of medi-cation rather than

part of the natural course of the disorder.

Stimulants

Small but significant reductions in inattention and hyperactivity ratings may be seen in children with autistic disorder in response to stimulants such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine

In a placebo-controlled crossover study, eight of

13 subjects showed a reduction of at least 50% on methylphenidate (Handen et al., 2000). However, stereotypies may

worsen, so drug trials for the

individual patient must always be assessed to determine whether the therapeutic

effects outweigh side effects. A key dis-tinction in assessing attentional

problems of children with ASD is the distinction between poor sustained

attention (characteris-tic of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder) and poor joint attention (characteristic of children with autistic

disor-der). Problems in joint attention require educational and behavio-ral

interventions or treatment of rituals with an SSRI. Problems in maintenance of

attention of the type seen in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder are

more likely to respond to stimulants.

Sympatholytics

The alpha-2-adrenergic receptor agonist

clonidine reduced irri-tability as well as hyperactivity and impulsivity in two

double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. However, tolerance developed several

months after initiation of the treatment in each child who was treated long

term but may have been reduced in several cases by administering clonidine in

the morning and then 6 to 8 hours later with a 16- to 18-hour interval between

the last dose of one day and the first dose of the next day. If tolerance does

develop, the dose should not be increased because tolerance to sedation does

not occur, and sedation may lead to increased ag-gression due to disinhibition

or decreased cognitive control of impulses. Adrenergic receptor antagonists,

such as propranolol and naldolol, have not been tested in double-blind trials

in ASD. However, open trials have reported the use of these medications in the treatment

of aggression and impulsivity in developmental disorders including autistic

disorder.

Neuroleptics

Typical Neuroleptics

Because they were among the first modern

psychopharmaco-logical agents, typical neuroleptics have been among the most

extensively studied drugs in autistic disorder. Trifluoperazine, thioridazine,

haloperidol and pimozide have been studied in dou-ble-blind, controlled trials

lasting from 2 to 6 months. Reduction of fidgetiness, interpersonal withdrawal,

speech deviance and stereotypes has been documented in response to these.

How-ever, patients with autistic disorder are as vulnerable to poten-tially

irreversible tardive dyskinesia as any other group of young patients. Owing to

the often earlier age at initiation of pharma-cotherapy, patients with ASD

treated with typical neuroleptics may be at higher risk because of the

potential increased lifetime exposure of medication limiting their routine use

in the care of patients with ASD, especially as first-line treatments.

Atypical Neuroleptics

Because of the positive response of many children

with autis-tic disorder to typical neuroleptics, similar medications with

re-duced risk of tardive dyskinesia must be considered. In addition, atypical

neuroleptics are often effective in treating the negative symptoms of

schizophrenia, which seem similar to several of the social deficits in autistic

disorder. Both risperidone and olanzap-ine have shown promise in open label

trials in reducing hyperac-tivity, impulsivity, aggressiveness and obsessive

preoccupations.

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study found

risperidone to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of repetitive

behav-ior, aggression and irritability (McDougle et al., 1998).

Anticonvulsants

Because 25 to 33% of patients with autistic

disorder have seizures, the psychopharmacological management of patients with

autistic disorder or other ASD must take into consideration the past or current

history of epilepsy and the potential role of anticonvulsants. In an open trial

of divalproex, 10 of 14 patients responded favorably, showing improvements in

affective stability, impulsivity and aggression (Hollander et al., 2001). Because barbiturates have been associated with

hyperactivity, depression and cognitive impairment, they should be changed to

an alternative drug, depending on the seizure and avoided when possible. In

addition, phenytoin (Dilantin) is sedating and can cause hypertrophy of the

gums and hirsutism, which may contribute to the social challenges for people

with autistic disorder. Carbamazepine and valproate may have positive

psychotropic effects, particularly when cyclical irritability, insomnia and

hyperactivity are present.

Naltrexone

Double-blind trials have demonstrated that

naltrexone, an opiate antagonist, has little efficacy in treating the core

social and cognitive symptoms of autistic. While the use of naltrexone as a

specific treatment for autistic disorder no longer seems to be likely, it may

have a role in the treatment of self-injurious behavior, although the

controlled data are equivocal. Controlled trials have shown a modest reduction

in symptoms of hyperactivity and restlessness sometimes associated with

autistic disorder. Potential side effects include nausea and vomiting.

Naltrexone may have an adverse effect on the outcome of Rett’s disorder on the

basis of a relatively large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

(Percy et al., 1994).

Lithium

Adolescents and adults with autistic disorder often

exhibit symp-toms in a cyclic manner and so there is much interest in how these

patients might respond to agents typically used in bipolar disorder. A single

open trial of lithium revealed no significant im-provement in symptoms in

patients with autistic disorder without bipolar disorder (Campbell et al., 1972).

Anxiolytics

Benzodiazepines have not been studied

systematically in chil-dren and adolescents with autistic disorder. However,

their use to reduce anxiety in short-term treatment, such as before dental

procedures, is similar to their use in management of anxiety in people without

a PDD. One open label study has found a decrease in anxiety and irritability in

patients receiving the anxiolytic bus-pirone (Buitelaar et al., 1998).

Glutamatergic Antagonists

Interest in these agents has been sparked by the

hypothesis that ASDs may be a disorder of hypoglutaminergic activity. In a

dou-ble-blind, placebo-controlled study of the glutamatergic antago-nist

amantadine hydrochloride, there were substantial improve-ments in

clinician-rated hyperactivity and irritability, although parental reports did

not reach statistical significance (King et

al., 2001).

Other Treatments

Pyridoxine,

the water-soluble essential vitamin B6, has been used extensively as

a pharmacological treatment in autistic disorder. In the doses used for autistic

disorder, it is not being used as a cofactor for normally regulated enzyme

function or as a vita-min; rather, it is used to modulate the function of

neurotrans-mitter enzymes, such as tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine

hydroxylase. Recent reviews have concluded that there are little data to

support the claim that vitamin B6 improves developmental course. The

same is true for using fenfluramine, naloxone and secretin.

Related Topics