Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Obstetric Anesthesia

Anesthesia for Hypertensive Disorders

HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS

Hypertension during pregnancy can be classified as pregnancy-induced

hypertension (PIH, often also referred to as preeclampsia), chronic

hypertension that preceded pregnancy, or chronic hypertension with superimposed

preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is usually defined as a systolic

blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm

Hg after the 20th week of ges-tation, accompanied by proteinuria (>300 mg/d)

and resolving within 48 h after delivery. When sei-zures occur, the syndrome is

termed eclampsia. The HELLP syndrome describes preeclampsia associated with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes,

and a lowplatelet count. In the United States, preeclampsiacomplicates

approximately 7–10% of pregnancies; eclampsia is much less common, occurring in

one of 10,000–15,000 pregnancies. Severe preeclamp-sia causes or contributes to

20–40% of maternal deaths and 20% of perinatal deaths. Maternal deaths are

usually due to stroke, pulmonary edema, and hepatic necrosis or rupture.

Pathophysiology & Manifestations

The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is

probably related to a vascular dysfunction of the placenta that results in

abnormal prostaglandin metabolism. Patients with preeclampsia have elevated

production of thromboxane A2 (TXA2)

and decreased produc-tion of prostacyclin (PGI2). TXA2

is a potent vaso-constrictor and promoter of platelet aggregation, whereas PGI2 is a potent vasodilator and inhibitor of

platelet aggregation. Endothelial dysfunction may reduce production of nitric

oxide and increase pro-duction of endothelin-1. The latter is also a potent

vasoconstrictor and activator of platelets. Marked vascular reactivity and

endothelial injury reduce placental perfusion and can lead to widespread

sys-temic manifestations.

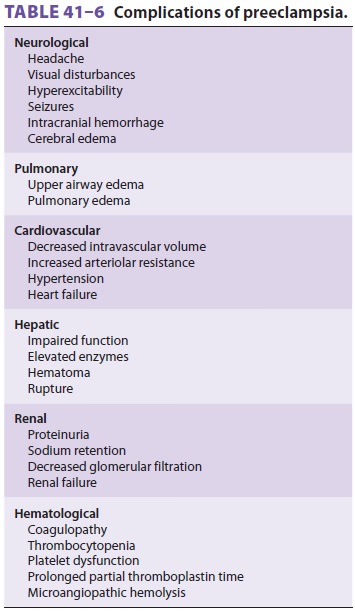

Severe preeclampsia substantially increases

both maternal and fetal morbidity and mortal-ity, and is defined by a blood

pressure greater than 160/110 mm Hg, proteinuria in excess of 5 g/d, oli-guria

(<500 mL/d), elevated

serum creatinine, intra-uterine growth restriction, pulmonary edema, central

nervous system manifestations (headache, visual dis-turbances, seizures, or

stroke), hepatic tenderness, or the HELLP syndrome (Table 41-6). Hepatic rupture may also occur in patients with the HELLP syndrome.

Patients with severe preeclampsia or

eclampsia have widely differing hemodynamic profiles. Most patients have

low-normal cardiac filling pressures with high systemic vascular resistance,

but cardiac output may be low, normal, or high.

Treatment

Treatment of preeclampsia consists of bed rest, seda-tion, repeated doses of antihypertensive drugs (usually labetalol, 5–10 mg, or hydralazine, 5 mg intrave-nously), and magnesium sulfate (4 g intravenous loading, followed by 1–3 g/h) to treat hyperreflexia and prevent convulsions. Therapeutic magnesium levels are 4–6 mEq/L.

Invasive arterial and central venous monitor-ing are indicated in

patients with severe hyperten-sion, pulmonary edema, or refractory oliguria; an

intravenous vasodilator infusion may be necessary. Definitive treatment of

preeclampsia is delivery of the fetus and placenta.

Anesthetic Management

Patients with mild preeclampsia generally

require only extra caution during anesthesia; standard anes-thetic practices

may be used. Spinal and epidural anesthesia are associated with similar

decreases in arterial blood pressure in these patients. Patients with severe

disease, however, are critically ill and require stabilization prior to

administration of any anesthetic. Hypertension should be controlled and

hypovolemia corrected before administration of anesthesia. In the absence of

coagulopathy, continuous epidural anes-thesia is the first choice for most

patients with pre-eclampsia during labor, vaginal delivery, and cesarean

section. Moreover, continuous epidural anesthesia avoids the increased risk of

a failed intubation due to severe edema of the upper airway.

A platelet count and coagulation profile

should be checked prior to the institution of regional anes-thesia in patients

with severe preeclampsia. It has been recommended that regional anesthesia be

avoided if the platelet count is less than 100,000/μL, but a platelet count as low as 70,000/μL may be acceptable in

selected cases, particularly when the count has been stable. Although some

patients have a qualitative platelet defect, the usefulness of a bleeding time

determination is questionable. Continuous epidural anesthesia has been shown to

decrease catecholamine secretion and improve uteroplacental perfusion up to 75%

in these patients, provided hypotension is avoided. Judicious fluid boluses

with epidural activation may be required to correct the disease-related

hypovolemia. Goal-directed hemodynamic and fluid therapy utiliz-ing arterial

pulse wave contour analysis (Virgileo/ Flotrac, LiDCOrapid) or echocardiography

may be employed to guide fluid replacement. Use of an epi-nephrine-containing

test dose for epidural anesthe-sia is controversial because of questionable

reliability (see earlier section Prevention of Unintentional Intravascular and

Intrathecal Injection) and the risk of exacerbating hypertension. Hypotension

should be treated with small doses of vasopressors because patients tend to be

very sensitive to these agents. Recent evidence suggests that spinal anesthesia

does not, as previously thought, result in a more severe reduction of maternal

blood pressure. Therefore, this technique is a reasonable anesthetic choice for

cesarean section in a preeclamptic patient.

Intraarterial blood pressure monitoring is

indi-cated in patients with severe hypertension during both general and

regional anesthesia. Intravenous vasodilator infusions may be necessary to

control blood pressure during general anesthesia. Intravenous labetalol (5–10

mg increments) can also be effective in controlling the hypertensive response

to intuba-tion and does not appear to alter placental blood flow. Because

magnesium potentiates muscle relaxants, doses of nondepolarizing muscle

relaxants should be reduced in patients receiving magnesium therapy and should

be guided by a peripheral nerve stimu-lator. The patient with suspected

magnesium toxic-ity, manifested by hyporef lexia, excessive sedation, blurred

vision, respiratory compromise and cardiac depression, can be treated with

intravenous admin-istration of calcium gluconate (1 g over 10 minutes).

Related Topics