Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Neurologic Function

Anatomy of the Peripheral Nervous System

The Peripheral Nervous System

The

peripheral nervous system includes the cranial nerves, the spinal nerves, and

the autonomic nervous system.

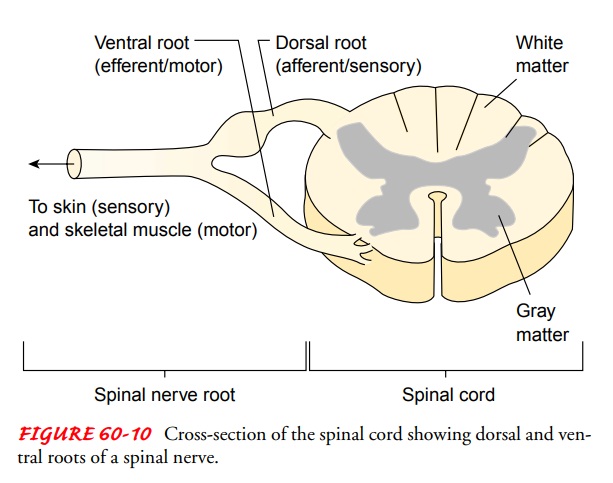

CRANIAL NERVES

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves that emerge

from the lower surface of the brain and pass through the foramina in the skull.

Three are entirely sensory (I, II, VIII), five are motor (III, IV, VI, XI, and

XII), and four are mixed (V, VII, IX, and X) as they have both sensory and

motor functions (Downey & Leigh, 1998; Hickey, 2003). The cranial nerves

are numbered in the order in which they arise from the brain. For example,

cranial nerves I andattach in the cerebral hemispheres, whereas cranial

nerves IX, X, XI, and XII attach at the medulla (Fig. 60-9). Most cranial

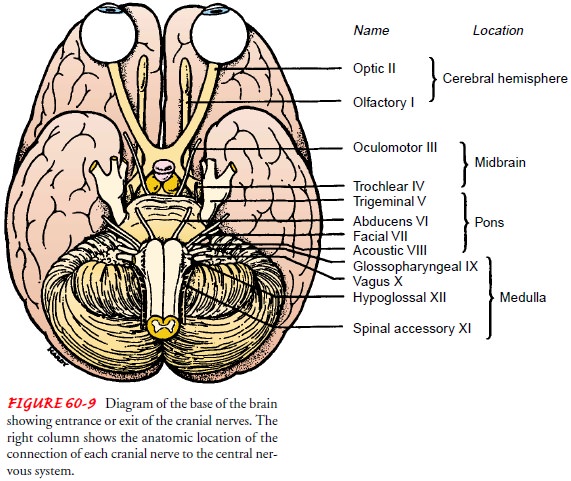

nerves innervate the head, neck, and special sense structures. Table 60-2 lists

the names and primary functions of the cranial nerves.

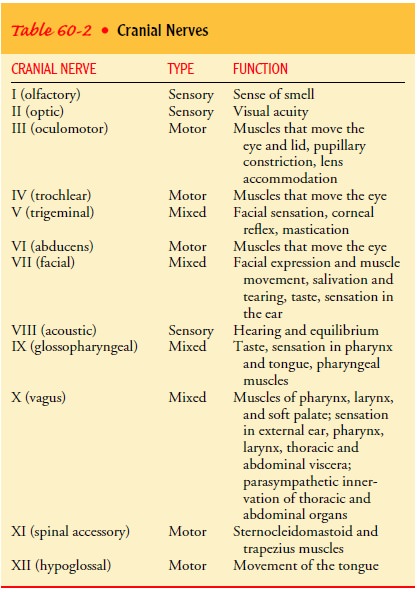

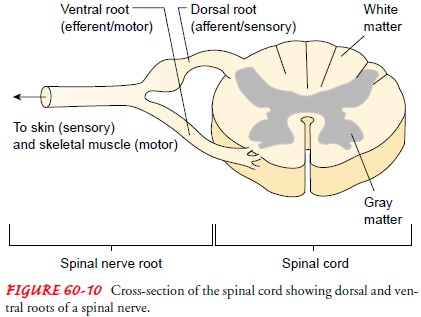

SPINAL NERVES

The

spinal cord is composed of 31 pairs of spinal nerves: 8 cervi-cal, 12 thoracic,

5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal. Each spinal nerve has a ventral root and a

dorsal root (Fig. 60-10).

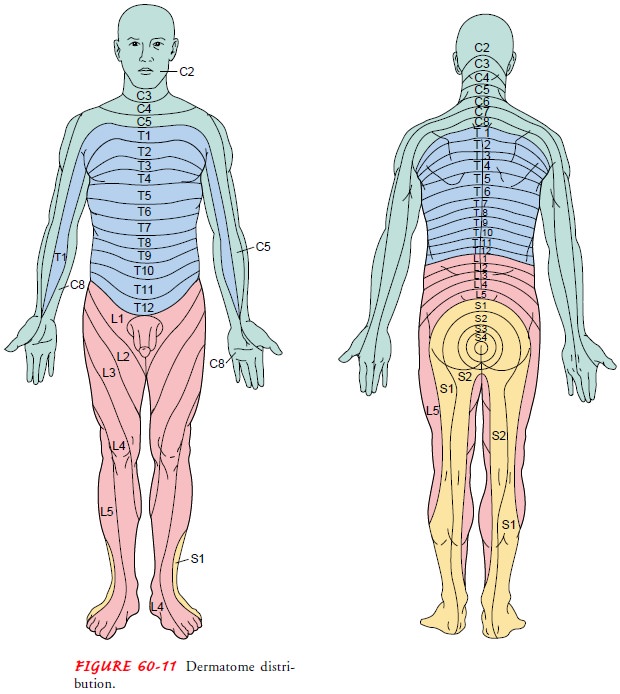

The dorsal roots are sensory and transmit sensory

impulses from specific areas of the body known as dermatomes (Fig. 60-11) to

the dorsal ganglia. The sensory fiber may be somatic, carrying information

about pain, temperature, touch, and position sense (proprioception) from the

tendons, joints, and body surfaces; or visceral, carrying information from the

internal organs.

The

ventral roots are motor and transmit impulses from the spinal cord to the body.

These fibers are also either somatic or vis-ceral. The visceral fibers include

autonomic fibers that control the cardiac muscles and glandular secretions.

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The autonomic nervous system regulates the activities of inter-nal organs such as the heart, lungs, blood vessels, digestive organs, and glands. Maintenance and restoration of internal homeostasis is largely the responsibility of the autonomic nervous system. There are two major divisions: the sympathetic nervous system, with predominantly excitatory responses, most notably the “fight or flight” response, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which controls mostly visceral functions.

The autonomic nervous system innervates most body organs. Although usually considered part of the peripheral nervous sys-tem, it is regulated by centers in the spinal cord, brain stem, and hypothalamus.

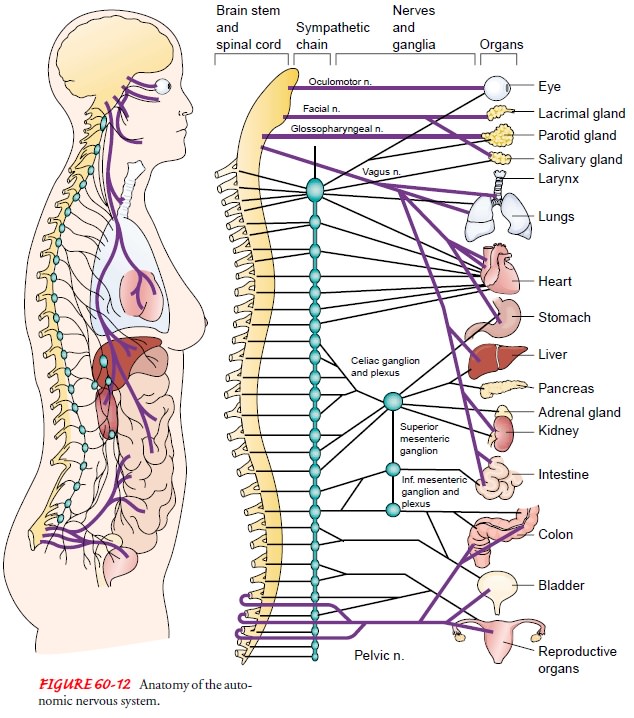

The autonomic nervous system has two

neurons in a series extending between the centers in the CNS and the or-gans

innervated. The first neuron, the preganglionic neuron, is located in the brain

or spinal cord, and its axon extends to the autonomic ganglia. There, it

synapses with the second neuron, the postganglionic neuron, located in the

autonomic ganglia, and its axon synapses with the target tissue and innervates

the effector organ. Its regulatory effects are exerted not on individual cells

but on large expanses of tissue and on entire organs. The responses elicited do

not occur instantaneously but after a lag period. These responses are sustained

far longer than other neurogenic re-sponses to ensure maximal functional

efficiency on the part of receptor organs, such as blood vessels.

The quality of these responses is explained by the

fact that the autonomic nervous system transmits its impulses by way of nerve

pathways, enhanced by chemical mediators, resembling in this re-spect the

endocrine system. Electrical impulses, conducted through nerve fibers,

stimulate the formation of specific chemical agents at strategic locations

within the muscle mass; the diffusion of these chemicals within the muscle is

responsible for the contraction.

The hypothalamus is the major subcortical center for the regulation of visceral and somatic activities, with an inhibitory– excitatory role in the autonomic nervous system. The hypothal-amus has connections that link the autonomic system with the thalamus, the cortex, the olfactory apparatus, and the pituitary gland. Located here are the mechanisms for the control of visceral and somatic reactions that were originally important for defense or attack, and are associated with emotional states (eg, fear, anger, anxiety); for the control of metabolic processes, including fat, carbohydrate, and water metabolism; for the regulation of body temperature, arterial pressure, and all muscular and glandular ac-tivities of the gastrointestinal tract; for control of genital functions; and for the sleep cycle.

The

autonomic nervous system is separated into the anatom-ically and functionally

distinct sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. Most of the tissues and the

organs under autonomic control are innervated by both systems. Sympathetic

stimuli are mediated by norepinephrine and parasympathetic impulses are

mediated by acetylcholine. These chemicals produce opposing and mutually antagonistic

effects. Both divisions produce stimu-latory and inhibitory effects. For

example, the parasympathetic division causes contraction (stimulation) of the

urinary bladder muscles and a decrease (inhibition) in heart rate, whereas the

sympathetic division produces relaxation (inhibition) of the uri-nary bladder

and an increase (stimulation) in the rate and force of the heartbeat. Table

60-3 compares the sympathetic and the parasympathetic effects on the different

systems of the body.

Sympathetic Nervous System.

The sympathetic division of theautonomic nervous

system is best known for its role in the body’s “fight-or-flight” response.

Under stress conditions from either physical or emotional causes, sympathetic

impulses increase greatly. As a result, the bronchioles dilate for easier gas

exchange; the heart’s contractions are stronger and faster; the arteries to the

heart and voluntary muscles dilate, carrying more blood to these organs;

peripheral blood vessels constrict, making the skin feel cool but shunting

blood to essential organs; the pupils dilate; the liver releases glucose for

quick energy; peristalsis slows; hair stands on end; and perspiration

increases. The sympathetic neurotrans-mitter is norepinephrine (noradrenaline),

and this increase in sympathetic discharge is the same as if the body has been

given an injection of adrenalin—hence, the term adrenergic is often used to

refer to this division.

Sympathetic neurons are located in the thoracic and

the lum-bar segments of the spinal cord; their axons, or the preganglionic

fibers, emerge by way of anterior nerve roots from the eighth cer-vical or

first thoracic segment to the second or third lumbar seg-ment. A short distance

from the cord, these fibers diverge to join a chain, composed of 22 linked

ganglia, that extends the entire length of the spinal column, adjacent to the

vertebral bodies on both sides. Some form multiple synapses with nerve cells

within the chain. Others traverse the chain without making connections or

losing continuity to join large “prevertebral” ganglia in the tho-rax, the

abdomen, or the pelvis or one of the “terminal” ganglia in the vicinity of an

organ, such as the bladder or the rectum (Fig. 60-12). Postganglionic nerve

fibers originating in the sym-pathetic chain rejoin the spinal nerves that

supply the extremities and are distributed to blood vessels, sweat glands, and

smooth muscle tissue in the skin. Postganglionic fibers from the prever-tebral

plexuses (eg, the cardiac, pulmonary, splanchnic, and pelvic plexuses) supply

structures in the head and neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, respectively,

having been joined in these plexuses by fibers from the parasympathetic

division.

The adrenal glands, kidneys, liver, spleen,

stomach, and duo-denum are under the control of the giant celiac plexus,

commonly known as the solar plexus. This receives its sympathetic nerve

components by way of the three splanchnic nerves, composed of preganglionic

fibers from nine segments of the spinal cord (T4 to L1), and is joined by the

vagus nerve, representing the parasym-pathetic division. From the celiac

plexus, fibers of both divisions travel along the course of blood vessels to

their target organs.

Sympathetic Syndromes.

Certain syndromes are

distinctive todiseases of the sympathetic nerve trunks. Among these are

dila-tion of the pupil of the eye on the same side as a penetrating wound of

the neck (evidence of disturbance of the cervical sym-pathetic cord); temporary

paralysis of the bowel (indicated by the absence of peristaltic waves and the distention of the

intestine by gas) after fracture of any one of the lower dorsal or upper lumbar

vertebrae with hemorrhage into the base of the mesentery; and the marked

variations in pulse rate and rhythm that often follow compression fractures of

the upper six thoracic vertebrae.

Parasympathetic Nervous System.

The parasympathetic nervoussystem functions as the dominant controller for most visceral ef-fectors. During quiet, nonstressful conditions, impulses from parasympathetic fibers (cholinergic) predominate. The fibers of the parasympathetic system are located in two sections, one in the brain stem and the other from spinal segments below L2. Be-cause of the location of these fibers, the parasympathetic system is referred to as the craniosacral division, as distinct from the tho-racolumbar (sympathetic) division of the autonomic nervous system.

The

parasympathetic nerves arise from the midbrain and the medulla oblongata.

Fibers from cells in the midbrain travel with the third oculomotor nerve to the

ciliary ganglia, where post-ganglionic fibers of this division are joined by

those of the sym-pathetic system, creating controlled opposition, with a

delicate balance maintained between the two at all times.

Related Topics