Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary Disorders

Anatomy and Function of the Gallbladder

ANATOMY OF THE GALLBLADDER

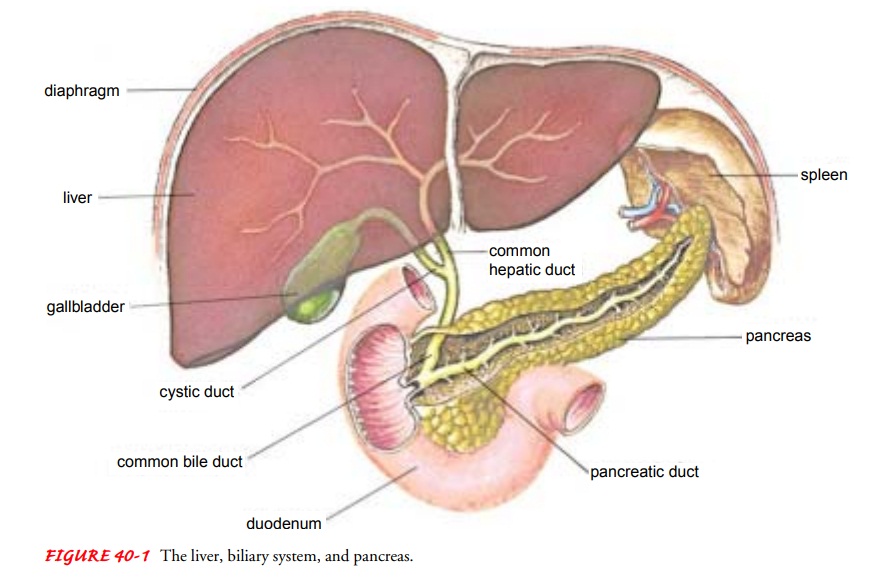

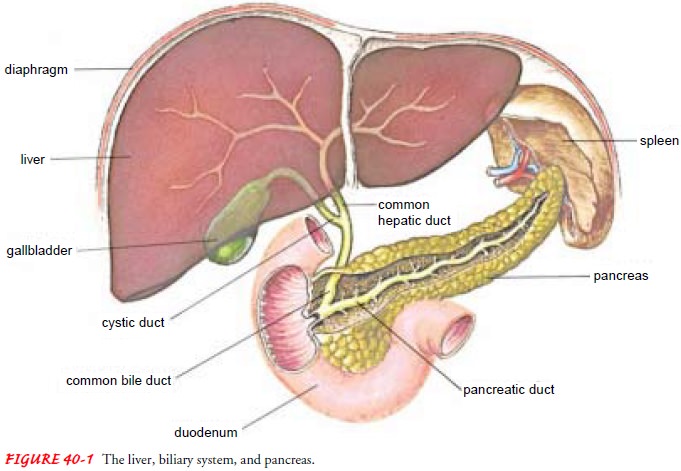

The

gallbladder, a pear-shaped, hollow, saclike organ, 7.5 to 10 cm (3 to 4 in)

long, lies in a shallow depression on the inferior sur-face of the liver, to

which it is attached by loose connective tissue. The capacity of the gallbladder

is 30 to 50 mL of bile. Its wall is composed largely of smooth muscle. The

gallbladder is connected to the common bile duct by the cystic duct (Fig.

40-1).

FUNCTION OF THE GALLBLADDER

The

gallbladder functions as a storage depot for bile. Between meals, when the

sphincter of Oddi is closed, bile produced by the hepatocytes enters the

gallbladder. During storage, a large portion of the water in bile is absorbed

through the walls of the gall-bladder, so that gallbladder bile is five to ten

times more concen-trated than that originally secreted by the liver. When food

enters the duodenum, the gallbladder contracts and the sphincter of Oddi

(located at the junction where the common bile duct en-ters the duodenum)

relaxes. Relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi allows the bile to enter the

intestine. This response is mediated by secretion of the hormone cholecystokinin–pancreozymin(CCK-PZ) from

the intestinal wall. Bile is composed of waterand electrolytes (sodium,

potassium, calcium, chloride, and bi-carbonate) and significant amounts of

lecithin, fatty acids, cho-lesterol, bilirubin, and bile salts. The bile salts,

together with cholesterol, assist in emulsification of fats in the distal

ileum. They then are reabsorbed into the portal blood for return to the liver

and again excreted into the bile. This pathway from hepatocytes to bile to

intestine and back to the hepatocytes is called the enterohepatic circulation.

Because of the enterohepatic cir-culation, only a small fraction of the bile

salts that enter the in-testine are excreted in the feces. This decreases the

need for active synthesis of bile salts by the liver cells.

If the

flow of bile is impeded (ie, with gallstones in the bile ducts), bilirubin, a

pigment derived from the breakdown of red blood cells, does not enter the

intestine. As a result, bilirubin levels in the blood increase. This results,

in turn, in increased renal excretion of urobilinogen, which results from

conversion of bilirubin in the small intestine, and decreased excretion in the

stool. These changes produce many of the signs and symptoms seen in gallbladder

disorders.

Related Topics