Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary Disorders

Cholelithiasis - Disorders of the Gallbladder

CHOLELITHIASIS

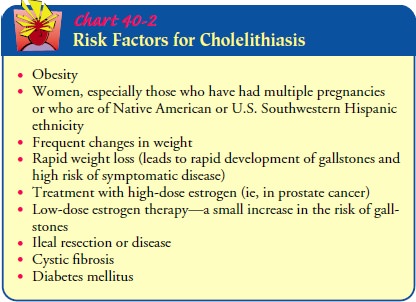

Calculi,

or gallstones, usually form in the gallbladder from the solid constituents of

bile; they vary greatly in size, shape, and com-position (Fig. 40-2). They are

uncommon in children and young adults but become increasingly prevalent after

40 years of age. The incidence of cholelithiasis increases thereafter to such

an ex-tent that up to 50% of those over the age of 70 and over 50% of those

over 80 will develop stones in the bile tract (Borzellino, deManzoni &

Ricci, 1999). Chart 40-2 identifies common risk factors.

Pathophysiology

There

are two major types of gallstones: those composed pre-dominantly of pigment and

those composed primarily of choles-terol. Pigment stones probably form when

unconjugated pigments in the bile precipitate to form stones; these stones

account for about one third of cases in the United States (Donovan, 1999). The

risk of developing such stones is increased in patients with cirrhosis,

hemolysis, and infections of the biliary tract. Pigment stones cannot be

dissolved and must be removed surgically.

Cholesterol

stones account for most of the remaining cases of gallbladder disease in the

United States. Cholesterol, a normal constituent of bile, is insoluble in

water. Its solubility depends on bile acids and lecithin (phospholipids) in

bile. In gallstone-prone patients, there is decreased bile acid synthesis and

increased cho-lesterol synthesis in the liver, resulting in bile supersaturated

with cholesterol, which precipitates out of the bile to form stones. The

cholesterol-saturated bile predisposes to the formation of gall-stones and acts

as an irritant, producing inflammatory changes in the gallbladder.

Four times more women than men develop cholesterol stones and gallbladder disease; the women are usually older than 40, multiparous, and obese. The incidence of stone formation rises in users of oral contraceptives, estrogens, and clofibrate; these substances are known to increase biliary cholesterol saturation. The incidence of stone formation increases with age as a result of increased hepatic secretion of cholesterol and decreased bile acid synthesis. In addition, there is an increased risk because of mal-absorption of bile salts in patients with gastrointestinal disease or T-tube fistula or in those who have had ileal resection or bypass.

The

incidence also increases in people with diabetes.

Clinical Manifestations

Gallstones

may be silent, producing no pain and only mild gastro-intestinal symptoms. Such

stones may be detected incidentally during surgery or evaluation for unrelated

problems.

The patient with gallbladder disease from gallstones may de-velop two types of symptoms: those due to disease of the gall-bladder itself and those due to obstruction of the bile passages by a gallstone. The symptoms may be acute or chronic. Epigastric distress, such as fullness, abdominal distention, and vague pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, may occur. This dis-tress may follow a meal rich in fried or fatty foods.

PAIN AND BILIARY COLIC

If a

gallstone obstructs the cystic duct, the gallbladder becomes distended,

inflamed, and eventually infected (acute cholecystitis). The patient develops a

fever and may have a palpable abdominal mass. The patient may have biliary

colic with excruciating upper right abdominal pain that radiates to the back or

right shoulder, is usually associated with nausea and vomiting, and is

noticeable several hours after a heavy meal. The patient moves about

rest-lessly, unable to find a comfortable position. In some patients the pain

is constant rather than colicky.

Such a

bout of biliary colic is caused by contraction of the gall-bladder, which

cannot release bile because of obstruction by the stone. When distended, the

fundus of the gallbladder comes in contact with the abdominal wall in the

region of the right ninth and tenth costal cartilages. This produces marked

tenderness in the right upper quadrant on deep inspiration and prevents full

in-spiratory excursion.

The

pain of acute cholecystitis may be so severe that analgesics are required.

Morphine is thought to increase spasm of the sphincter of Oddi and may be

avoided in many cases in favor of meperidine (Porth, 2002). This is

controversial because morphine is the preferred analgesic agent for management

of acute pain, and meperidine has metabolites toxic to the CNS.

If the

gallstone is dislodged and no longer obstructs the cystic duct, the gallbladder

drains and the inflammatory process sub-sides after a relatively short time. If

the gallstone continues to ob-struct the duct, abscess, necrosis, and

perforation with generalized peritonitis may result.

JAUNDICE

Jaundice

occurs in a few patients with gallbladder disease and usually occurs with

obstruction of the common bile duct. The bile, which is no longer carried to

the duodenum, is absorbed by the blood and gives the skin and mucous membrane a

yellow color. This is frequently accompanied by marked itching of the skin.

CHANGES IN URINE AND STOOL COLOR

The

excretion of the bile pigments by the kidneys gives the urine a very dark

color. The feces, no longer colored with bile pigments, are grayish, like

putty, and usually described as clay-colored.

VITAMIN DEFICIENCY

Obstruction

of bile flow also interferes with absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D,

E, and K. Therefore, the patient may ex-hibit deficiencies (eg, bleeding caused

by vitamin K deficiency, which interferes with normal blood clotting) of these

vitamins if biliary obstruction has been prolonged.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

ABDOMINAL X-RAY

An

abdominal x-ray may be obtained if gallbladder disease is sug-gested to exclude

other causes of symptoms. However, only 15% to 20% of gallstones are calcified

sufficiently to be visible on such x-ray studies.

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasonography

has replaced oral cholecystography as the diag-nostic procedure of choice

because it is rapid and accurate and can be used in patients with liver

dysfunction and jaundice. It does not expose patients to ionizing radiation.

The procedure is most accurate if the patient fasts overnight so that the

gallbladder is distended. The use of ultrasound is based on reflected sound

waves. Ultrasonography can detect calculi in the gallbladder or a dilated common

bile duct. It is reported to detect gallstones with 95% accuracy.

RADIONUCLIDE IMAGING OR CHOLESCINTIGRAPHY

Cholescintigraphy is used successfully in the diagnosis of acute

cholecystitis. In this procedure, a radioactive agent is adminis-tered

intravenously. It is taken up by the hepatocytes and excreted rapidly through

the biliary tract. The biliary tract is then scanned, and images of the

gallbladder and biliary tract are obtained. This test is more expensive than

ultrasonography, takes longer to per-form, exposes the patient to radiation,

and cannot detect gall-stones. Its use may be limited to cases in which

ultrasonography is not conclusive.

CHOLECYSTOGRAPHY

Although

it has been replaced by ultrasonography as the test of choice, cholecystography

is still used if ultrasound equipment is not available or if the ultrasound

results are inconclusive. Oral cholangiography may be performed to detect

gallstones and to as-sess the ability of the gallbladder to fill, concentrate

its contents, contract, and empty. An iodide-containing contrast agent excreted

by the liver and concentrated in the gallbladder is administered to the

patient. The normal gallbladder fills with this radiopaque substance. If

gallstones are present, they appear as shadows on the x-ray film.

Contrast

agents include iopanoic acid (Telepaque), iodipamide meglumine (Cholografin),

and sodium ipodate (Oragrafin). These agents are administered orally 10 to 12

hours before the x-ray study. To prevent contraction and emptying of the

gallbladder, the patient is permitted nothing by mouth after the contrast agent

is administered.

The

patient is asked about allergies to iodine or seafood. If no allergy is

identified, the patient receives the oral form of the con-trast agent the

evening before the x-rays are obtained. An x-ray of the right upper abdomen is

obtained. If the gallbladder is found to fill and empty normally and to contain

no stones, gallbladder disease is ruled out. If gallbladder disease is present,

the gallblad-der may not be visualized because of obstruction by gallstones. A

repeat of the oral cholecystogram with a second dose of the con-trast agent may

be necessary if the gallbladder is not visualized on the first attempt.

Cholecystography

in the obviously jaundiced patient is not useful because the liver cannot

excrete the radiopaque dye into the gallbladder in the presence of jaundice.

Oral cholecys-tography is likely to continue to be used as part of the

evaluation of the few patients who have been treated with gallstone dissolu-tion therapy or lithotripsy.

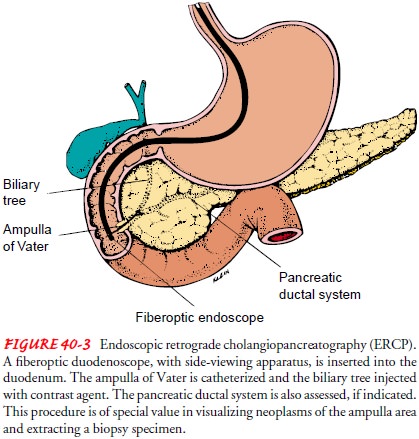

ENDOSCOPIC RETROGRADE CHOLANGIOPANCREATOGRAPHY

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)permits direct

visualization of structures that could once be seen only during laparotomy. The

examination of the hepatobiliary system is carried out via a side-viewing

flexible fiberoptic endo-scope inserted into the esophagus to the descending

duodenum (Fig. 40-3). Multiple position changes are required during the

procedure, beginning in the left semiprone position to pass the endoscope.

Fluoroscopy

and multiple x-rays are used during ERCP to evaluate the presence and location

of ductal stones. Careful in-sertion of a catheter through the endoscope into

the common bile duct is the most important step in sphincterotomy (division of the

muscles of the biliary sphincter) for gallstone extraction via this technique.

Nursing Implications.

The procedure requires a cooperative pa-tient to permit insertion of the endoscope without damage to the gastrointestinal tract structures, including the biliary tree.

Before the

procedure, the patient is given an explanation of the proce-dure and his or her

role in it. The patient takes nothing by mouth for several hours before the

procedure. Moderate sedation is used with this procedure, so the sedated

patient must be monitored closely. Most endoscopists use a combination of an

opioid and a benzodiazepine. Medications such as glucagon or anticholinergics

may also be necessary to eliminate duodenal peristalsis to make cannulation

easier. The nurse observes closely for signs of respi-ratory and central

nervous system depression, hypotension, over-sedation, and vomiting (if

glucagon is given). During ERCP, the nurse monitors intravenous fluids,

administers medications, and positions the patient.

After

the procedure, the nurse monitors the patient’s condi-tion, observing vital

signs and monitoring for signs of perforation or infection. The nurse also

monitors the patient for side effects of any medications received during the

procedure and for return of the gag and cough reflexes after the use of local

anesthetics.

PERCUTANEOUS TRANSHEPATIC CHOLANGIOGRAPHY

Percutaneous

transhepatic cholangiography involves the injection of dye directly into the

biliary tract. Because of the relatively large concentration of dye that is

introduced into the biliary system, all components of the system, including the

hepatic ducts within the liver, the entire length of the common bile duct, the

cystic duct, and the gallbladder, are outlined clearly.

This

procedure can be carried out even in the presence of liver dysfunction and

jaundice. It is useful for distinguishing jaundice caused by liver disease

(hepatocellular jaundice) from that caused by biliary obstruction, for

investigating the gastrointestinal symp-toms of a patient whose gallbladder has

been removed, for locating stones within the bile ducts, and for diagnosing

cancer involving the biliary system.

This

sterile procedure is performed under moderate sedation on a patient who has

been fasting; the patient receives local anesthesia and intravenous sedation.

Coagulation parameters and platelet count should be normal to minimize the risk

for bleeding. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered during the procedure

due to the high prevalence of bacterial coloniza-tion from obstructed biliary

systems. After infiltration with a local anesthetic agent, a flexible needle is

inserted into the liver from the right side in the midclavicular line

immediately be-neath the right costal margin. Successful entry of a duct is

noted when bile is aspirated or upon the injection of a contrast agent.

Ultrasound guidance can be used for duct puncture. Bile is as-pirated and

samples are sent for bacteriology and cytology. A water-soluble contrast agent

is injected to fill the biliary system. The fluoroscopy table is tilted and the

patient repositioned to allow x-rays to be taken in multiple projections.

Delayed x-ray views can identify abnormalities of more distant ducts and

de-termine the length of a stricture or multiple strictures. Before the needle

is removed, as much dye and bile as possible are as-pirated to forestall

subsequent leakage into the needle tract and eventually into the peritoneal

cavity, thus minimizing the risk of bile peritonitis.

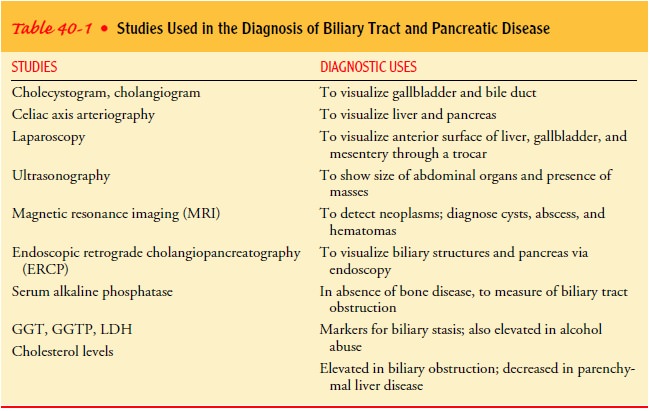

Table

40-1 identifies various procedures and their diagnostic uses.

Medical Management

The

major objectives of medical therapy are to reduce the inci-dence of acute

episodes of gallbladder pain and cholecystitis by supportive and dietary

management and, if possible, to remove the cause of cholecystitis by

pharmacologic therapy, endoscopic procedures, or surgical intervention.

Although nonsurgical approaches have the advantage of elim-inating risks associated with surgery, they are associated with per-sistent symptoms or recurrent stone formation. Most of the nonsurgical approaches, including lithotripsy and dissolution of gallstones, provide only temporary solutions to the problems as-sociated with gallstones. They are therefore rarely used in the United States. In some instances, other treatment approaches may be indicated; these are described below.

Removal

of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy)

through tradi-tional surgical approaches was considered the standard approach

to management for more than 100 years. However, dramatic changes have occurred

in the surgical management of gallbladder disease. There is now widespread use

of laparoscopic cholecys-tectomy (removal

of the gallbladder through a small incisionthrough the umbilicus). As a result,

surgical risks have decreased, along with the length of hospital stay and the

long recovery pe-riod associated with the standard surgical cholecystectomy.

NUTRITIONAL AND SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

Approximately

80% of the patients with acute gallbladder inflam-mation achieve remission with

rest, intravenous fluids, nasogastric suction, analgesia, and antibiotic

agents. Unless the patient’s con-dition deteriorates, surgical intervention is

delayed until the acute symptoms subside and a complete evaluation can be

carried out.

The

diet immediately after an episode is usually limited to low-fat liquids. The

patient can stir powdered supplements high in protein and carbohydrate into

skim milk. Cooked fruits, rice or tapioca, lean meats, mashed potatoes, non–gas-forming

veg-etables, bread, coffee, or tea may be added as tolerated. The pa-tient

should avoid eggs, cream, pork, fried foods, cheese and rich dressings,

gas-forming vegetables, and alcohol. It is important to remind the patient that

fatty foods may bring on an episode. Di-etary management may be the major mode

of therapy in patients who have had only dietary intolerance to fatty foods and

vague gastrointestinal symptoms (Dudek, 2001).

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Ursodeoxycholic

acid (UDCA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (che-nodiol or CDCA) have been used to

dissolve small, radiolucent gallstones composed primarily of cholesterol. UDCA

has fewer side effects than chenodiol and can be administered in smaller doses

to achieve the same effect. It acts by inhibiting the synthe-sis and secretion

of cholesterol, thereby desaturating bile. Exist-ing stones can be reduced in

size, small ones dissolved, and new stones prevented from forming. Six to 12

months of therapy are required in many patients to dissolve stones, and monitoring

of the patient is required during this time. The effective dose of medication

depends on body weight. This method of treatment is generally indicated for

patients who refuse surgery or for whom surgery is considered too risky.

Patients

with significant, frequent symptoms, cystic duct oc-clusion, or pigment stones

are not candidates for this therapy. Symptomatic patients with acceptable

operative risk are more ap-propriate for laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy.

NONSURGICAL REMOVAL OF GALLSTONES

Dissolving Gallstones.

Several

methods have been used to dis-solve gallstones by infusion of a solvent

(mono-octanoin or methyl tertiary butyl ether [MTBE]) into the gallbladder. The

solvent can be infused through the following routes: a tube or catheter

inserted percutaneously directly into the gallbladder; a tube or drain inserted

through a T-tube tract to dissolve stones not removed at the time of surgery;

an ERCP endoscope; or a transnasal biliary catheter.

In the

last procedure, the catheter is introduced through the mouth and inserted into

the common bile duct. The upper end of the tube is then rerouted from the mouth

to the nose and left in place. This enables the patient to eat and drink

normally while passage of stones is monitored or chemical solvents are infused

to dissolve the stones. This method of dissolution of stones is not widely used

in patients with gallstone disease.

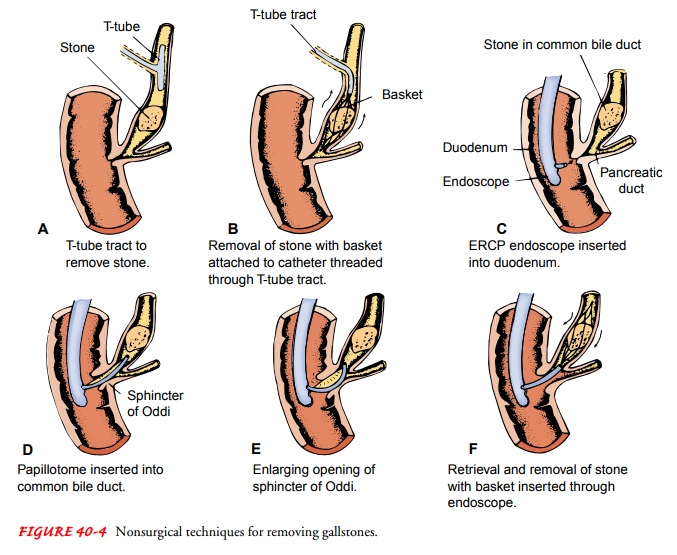

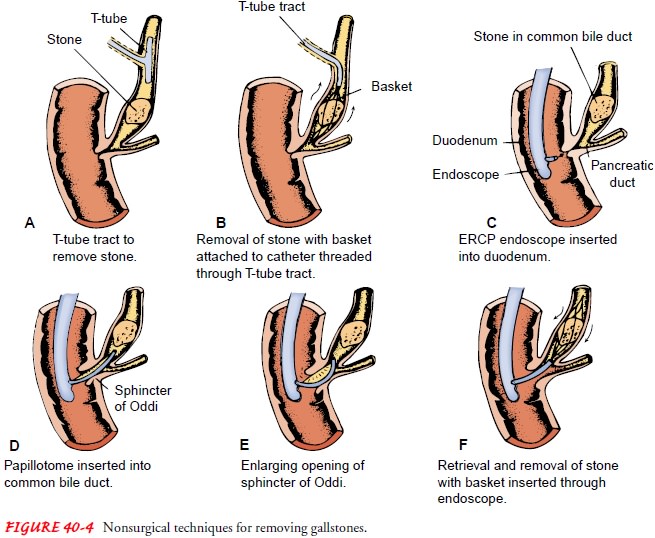

Stone Removal by Instrumentation.

Several

nonsurgical meth-ods are used to remove stones that were not removed at the

time of cholecystectomy or have become lodged in the common bile duct (Fig.

40-4A, B). A catheter and instrument

with a basket at-tached are threaded through the T-tube tract or fistula formed

at the time of T-tube insertion; the basket is used to retrieve and re-move the

stones lodged in the common bile duct.

A

second procedure involves the use of the ERCP endoscope (see Fig. 40-4C ). After the endoscope is inserted, a

cutting in-strument is passed through the endoscope into the ampulla of Vater

of the common bile duct. It may be used to cut the sub-mucosal fibers, or

papilla, of the sphincter of Oddi, enlarging the opening, which may allow the

lodged stones to pass spontaneously into the duodenum. Another instrument with

a small basket or balloon at its tip may be inserted through the endoscope to

retrieve the stones (see Fig. 40-4D–F

). Although complications after this procedure are rare, the patient must be

observed closely for bleed-ing, perforation, and the development of

pancreatitis or sepsis.

The

ERCP procedure is particularly useful in the diagnosis and treatment of

patients who have symptoms after biliary tract surgery, for patients with

intact gallbladders, and for patients in whom surgery is particularly

hazardous.

Extracorporeal Shock-Wave Lithotripsy.

Extracorporeal

shock-wave therapy (lithotripsy or ESWL) has been used for nonsurgi-cal

fragmentation of gallstones. The word lithotripsy

is derived from lithos, meaning

stone, and tripsis, meaning rubbing

or fric-tion. This noninvasive procedure uses repeated shock waves di-rected at

the gallstones in the gallbladder or common bile duct to fragment the stones.

The energy is transmitted to the body through a fluid-filled bag, or it may be

transmitted while the pa-tient is immersed in a water bath. The converging

shock waves are directed to the stones to be fragmented.

After

the stones are gradually broken up, the stone fragments pass from the

gallbladder or common bile duct spontaneously, are removed by endoscopy, or are

dissolved with oral bile acid or solvents. Because the procedure requires no

incision and no hos-pitalization, patients are usually treated as outpatients,

but several sessions are generally necessary.

The

advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy has reduced the use of this method to

treat gallbladder stones. It is used in some centers for a small percentage of

suitable patients (those with common bile duct stones who may not be surgical

candidates), sometimes in combination with dissolution therapy.

Intracorporeal Lithotripsy.

Stones in the gallbladder or commonbile duct may be fragmented by means of laser pulse technology. A laser pulse is directed under fluoroscopic guidance with the use of devices that can distinguish between stones and tissue. The laser pulse produces rapid expansion and disintegration of plasma on the stone surface, resulting in a mechanical shock wave. Electro-hydraulic lithotripsy uses a probe with two electrodes that deliver electric sparks in rapid pulses, creating expansion of the liquid environment surrounding the gallstones. This results in pressure waves that cause stones to fragment. This technique can be em-ployed percutaneously with the use of a basket or balloon catheter system or by direct visualization through an endoscope. Repeated procedures may be necessary due to stone size, local anatomy, bleeding, or technical difficulty. A nasobiliary tube can be inserted to allow for biliary decompression and prevent stone impaction in the common bile duct. This approach allows time for improve-ment in the patient’s clinical condition until gallstones are cleared endoscopically, percutaneously, or surgically.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical

treatment of gallbladder disease and gallstones is carried out to relieve

persistent symptoms, to remove the cause of biliary colic, and to treat acute

cholecystitis. Surgery may be delayed until the patient’s symptoms have

subsided or may be performed as an emergency procedure if the patient’s

condition necessitates it.

Preoperative Measures.

A chest

x-ray, electrocardiogram, andliver function tests may be performed in addition

to x-ray studies of the gallbladder. Vitamin K may be administered if the

pro-thrombin level is low. Blood component therapy may be admin-istered before

surgery. Nutritional requirements are considered; if the nutritional status is

suboptimal, it may be necessary to pro-vide intravenous glucose with protein

hydrolysate supplements to aid wound healing and help prevent liver damage.

Preparation

for gallbladder surgery is similar to that for any upper abdominal laparotomy

or laparoscopy. Instructions and explanations are given before surgery with

regard to turning and deep breathing. Pneumonia and atelectasis are possible

postoper-ative complications that can be avoided by deep-breathing exer-cises

and frequent turning. The patient should be informed that drainage tubes and a

nasogastric tube and suction may be re-quired during the immediate

postoperative period if an open cholecystectomy is performed.

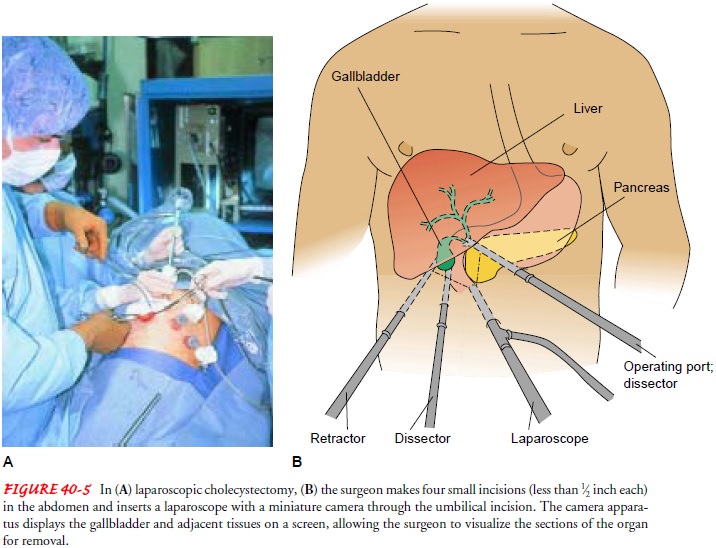

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy(Fig. 40-5) has dramatically changed the approach to the

man-agement of cholecystitis. It has become the new standard for ther-apy of

symptomatic gallstones. Approximately 700,000 patients in the United States

require surgery each year for removal of the gallbladder, and 80% to 90% of

them are candidates for laparo-scopic cholecystectomy (Bornman &

Beckingham, 2001). If the common bile duct is thought to be obstructed by a

gallstone, an ERCP with sphincterotomy may be performed to explore the duct

before laparoscopy.

Before

the procedure, the patient is informed that an open ab-dominal procedure may be

necessary, and general anesthesia is administered. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

is performed through a small incision or puncture made through the abdominal

wall in the umbilicus. The abdominal cavity is insufflated with carbon dioxide

(pneumoperitoneum) to assist in inserting the laparo-scope and to aid the

surgeon in visualizing the abdominal struc-tures. The fiberoptic scope is

inserted through the small umbilical incision. Several additional punctures or

small incisions are made in the abdominal wall to introduce other surgical

instruments into the operative field. The surgeon visualizes the biliary system

through the laparoscope; a camera attached to the scope permits a view of the

intra-abdominal field to be transmitted to a televi-sion monitor. After the

cystic duct is dissected, the common bile duct is imaged by ultrasound or

cholangiography to evaluate the anatomy and identify stones. The cystic artery

is dissected free and clipped. The gallbladder is separated away from the

hepatic bed and dissected. The gallbladder is then removed from the ab-dominal

cavity after bile and small stones are aspirated. Stone for-ceps also can be

used to remove or crush larger stones.

The

advantage of the laparoscopic procedure is that the pa-tient does not

experience the paralytic ileus that occurs with open abdominal surgery and has

less postoperative abdominal pain. The patient is often discharged from the

hospital on the day of surgery or within a day or two and can resume full

activity and employment within a week of the surgery.

Conversion to a traditional abdominal surgical procedure may be necessary if problems are encountered during the laparoscopic procedure; this occurs in 2% to 8% of reported surgical cases.

Conversion

is required more often, approximately 20% of the time, in those with acute

cholecystitis (Lai et al., 1998). Careful screening of patients and

identification of those at low risk for complications limits the frequency of

conversion to an open ab-dominal procedure. With wider use of laparoscopic

procedures, however, there may be an increase in the number of such con-versions.

The most serious complication after laparoscopic chole-cystectomy is a bile

duct injury.

Because

of the short hospital stay, it is important to provide written as well as

verbal instructions about managing postopera-tive pain and reporting signs and

symptoms of intra-abdominal complications, including loss of appetite,

vomiting, pain, disten-tion of the abdomen, and temperature elevation. Although

re-covery from laparoscopic cholecystectomy is rapid, patients are drowsy

afterward. The nurse must ensure that the patient has as-sistance at home

during the first 24 to 48 hours. If pain occurs in the right shoulder or

scapular area (from migration of the CO2 used to insufflate the abdominal cavity

during the procedure), the nurse may recommend use of a heating pad for 15 to

20 minutes hourly, walking, and sitting up when in bed.

Cholecystectomy.

In this

procedure, the gallbladder is removedthrough an abdominal incision (usually

right subcostal) after the cystic duct and artery are ligated. The procedure is

performed for acute and chronic cholecystitis. In some patients a drain may be

placed close to the gallbladder bed and brought out through a punc-ture wound

if there is a bile leak. The drain type is chosen based on the physician’s

preference. A small leak should close spontaneously in a few days with the

drain preventing accumulation of bile. Usu-ally only a small amount of

serosanguinous fluid will drain in the initial 24 hours after surgery, and then

the drain will be removed.

The drain is usually maintained if there is

excess oozing or bile leak-age. Use of a T-tube inserted into the common bile

duct during the open procedure is now uncommon; it is used only in the setting

of a complication (ie, retained common bile duct stone). Bile duct in-jury is a

serious complication of this procedure but occurs less fre-quently than with

the laparoscopic approach. Once one of the most common surgical procedures in

the United States, this procedure has largely been replaced by laparoscopic

cholecystectomy.

Mini-cholecystectomy.

Mini-cholecystectomy

is a surgical pro-cedure in which the gallbladder is removed through a small

inci-sion. If needed, the surgical incision is extended to remove large

gallbladder stones. Drains may or may not be used. The cost sav-ings resulting

from the shorter hospital stay have been `identified as a major reason for

pursuing this type of procedure. Debate ex-ists about this procedure because it

limits exposure to all the in-volved biliary structures.

Choledochostomy.

Choledochostomyinvolves an

incision intothe common duct, usually for removal of stones. After the stones

have been evacuated, a tube usually is inserted into the duct for drainage of

bile until edema subsides. This tube is connected to gravity drainage tubing.

The gallbladder also contains stones, and as a rule a cholecystectomy is

performed at the same time.

Surgical Cholecystostomy.

Cholecystostomyis performed

whenthe patient’s condition prevents more extensive surgery or when an acute

inflammatory reaction is severe. The gallbladder is surgically opened, the

stones and the bile or the purulent drainage are removed, and a drainage tube

is secured with a purse-string suture. The drainage tube is connected to a

drainage system to prevent

bile from leaking around the tube or escaping into the peritoneal cavity. After

recovery from the acute episode, the pa-tient may return for cholecystectomy.

Despite its lower risk, sur-gical cholecystostomy has a high mortality rate

(reported as high as 20% to 30%) because of the underlying disease process.

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy.

Percutaneous

cholecystostomyhas been used in the treatment and diagnosis of acute

cholecysti-tis in patients who are poor risks for any surgical procedure or for

general anesthesia. These may include patients with sepsis or se-vere cardiac,

renal, pulmonary, or liver failure. Under local anes-thesia, a fine needle is

inserted through the abdominal wall and liver edge into the gallbladder under

the guidance of ultrasound or computed tomography. Bile is aspirated to ensure

adequate placement of the needle, and a catheter is inserted into the

gall-bladder to decompress the biliary tract. Almost immediate relief of pain

and resolution of signs and symptoms of sepsis and chole-cystitis have been

reported with this procedure. Antibiotic agents are administered before,

during, and after the procedure.

Gerontologic Considerations

Surgical

intervention for disease of the biliary tract is the most common operative

procedure performed in the elderly. Choles-terol saturation of bile increases

with age due to increased hepatic secretion of cholesterol and decreased bile

acid synthesis.

Although

the incidence of gallstones increases with age, the el-derly patient may not

exhibit the typical picture of fever, pain, chills, and jaundice. Symptoms of

biliary tract disease in the el-derly may be accompanied or preceded by those

of septic shock, which include oliguria, hypotension, changes in mental status,

tachycardia, and tachypnea.

Although

surgery in the elderly presents a risk because of pre-existing associated

diseases, the mortality rate from serious com-plications from biliary tract

disease itself is also high. The risk of death and complications is increased

in the elderly patient who undergoes emergency surgery for life-threatening

disease of the biliary tract. Despite chronic illness in many elderly patients,

elec-tive cholecystectomy is usually well tolerated and can be carried out with

low risk if expert assessment and care are provided be-fore, during, and after

the surgical procedure.

Because

of recent changes in the health care system, there has been a decrease in the

number of elective surgical procedures performed, including cholecystectomies.

As a result, patients requiring the procedure are seen in the later stages of

disease. Simultaneously, patients undergoing surgery are increasingly older

than 60 years of age and have complicated acute cholecys-titis. The higher risk

of complications and shorter hospital stays make it essential that older

patients and their family members re-ceive specific information about signs and

symptoms of compli-cations and measures to prevent them.

Related Topics