Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary Disorders

Acute Pancreatitis - Disorders of the Pancreas

ACUTE

PANCREATITIS

Acute

pancreatitis ranges from a mild, self-limiting disorder to a severe, rapidly

fatal disease that does not respond to any treat-ment. Mild acute pancreatitis

is characterized by edema and in-flammation confined to the pancreas. Minimal

organ dysfunction is present, and return to normal usually occurs within 6

months. Although this is considered the milder form of pancreatitis, the

patient is acutely ill and at risk for hypovolemic shock, fluid and electrolyte

disturbances, and sepsis. A more widespread and com-plete enzymatic digestion

of the gland characterizes severe acute pancreatitis. The tissue becomes

necrotic, and the damage ex-tends into the retroperitoneal tissues. Local

complications consist of pancreatic cysts or abscesses and acute fluid

collections in or near the pancreas. Systemic complications, such as acute

respira-tory distress syndrome, shock, disseminated intravascular

coagu-lopathy, and pleural effusion, can increase the mortality rate to 50% or

higher (Aronson, 1999).

Gerontologic Considerations

Acute

pancreatitis affects people of all ages, but the mortality rate associated with

acute pancreatitis increases with advancing age. In addition, the pattern of

complications changes with age. Younger patients tend to develop local

complications; the incidence of multiple organ failure increases with age,

possibly as a result of progressive decreases in physiologic function of major

organs with increasing age. Close monitoring of major organ function (ie,

lungs, kidneys) is essential, and aggressive treatment is neces-sary to reduce

mortality from acute pancreatitis in the elderly.

Pathophysiology

Self-digestion

of the pancreas by its own proteolytic enzymes, principally trypsin, causes

acute pancreatitis. Eighty percent of patients with acute pancreatitis have

biliary tract disease; how-ever, only 5% of patients with gallstones develop

pancreatitis. Gallstones enter the common bile duct and lodge at the ampulla of

Vater, obstructing the flow of pancreatic juice or causing a re-flux of bile

from the common bile duct into the pancreatic duct, thus activating the

powerful enzymes within the pancreas. Nor-mally, these remain in an inactive

form until the pancreatic se-cretions reach the lumen of the duodenum.

Activation of the enzymes can lead to vasodilation, increased vascular

permeabil-ity, necrosis, erosion, and hemorrhage (Quillen, 2001).

Long-term

use of alcohol is commonly associated with acute episodes of pancreatitis, but

the patient usually has had un-diagnosed chronic pancreatitis before the first

episode of acute pancreatitis occurs. Other less common causes of pancreatitis

in-clude bacterial or viral infection, with pancreatitis a complication of

mumps virus. Spasm and edema of the ampulla of Vater, re-sulting from

duodenitis, can probably produce pancreatitis. Blunt abdominal trauma, peptic

ulcer disease, ischemic vascular disease, hyperlipidemia, hypercalcemia, and

the use of corticosteroids, thi-azide diuretics, and oral contraceptives also

have been associated with an increased incidence of pancreatitis. Acute

pancreatitis may follow surgery on or near the pancreas or after

instrumentation of the pancreatic duct. Acute idiopathic pancreatitis accounts

for up to 20% of the cases of acute pancreatitis (Hale, Moseley & Warner,

2000). In addition, there is a small incidence of hereditary pancreatitis.

The

mortality rate of patients with acute pancreatitis is high (10%) because of

shock, anoxia, hypotension, or fluid and elec-trolyte imbalances. Attacks of

acute pancreatitis may result in complete recovery, may recur without permanent

damage, or may progress to chronic pancreatitis. The patient admitted to the

hospital with a diagnosis of pancreatitis is acutely ill and needs expert

nursing and medical care.

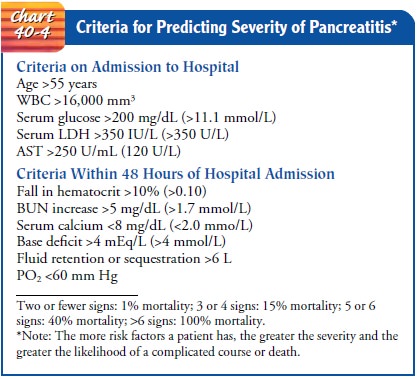

Severity

and mortality predictions of acute alcoholic pancre-atitis are generally

assessed using Ranson’s criteria (Tierney,McPhee& Papadakis, 2001). The

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) grading system may also

be used. Predictors of the severity of pancreatitis and its prognosis are listed

in Chart 40-4.

Clinical Manifestations

Severe

abdominal pain is the major symptom of pancreatitis that causes the patient to

seek medical care. Abdominal pain and ten-derness and back pain result from

irritation and edema of the in-flamed pancreas that stimulate the nerve

endings. Increased tension on the pancreatic capsule and obstruction of the

pan-creatic ducts also contribute to the pain. Typically, the pain oc-curs in

the midepigastrium. Pain is frequently acute in onset, occurring 24 to 48 hours

after a very heavy meal or alcohol in-gestion, and it may be diffuse and

difficult to localize. It is gen-erally more severe after meals and is

unrelieved by antacids. Pain may be accompanied by abdominal distention; a

poorly defined, palpable abdominal mass; and decreased peristalsis. Pain caused

by pancreatitis is accompanied frequently by vomiting that does not relieve the

pain or nausea.

The

patient appears acutely ill. Abdominal guarding is pres-ent. A rigid or

board-like abdomen may develop and is generally an ominous sign; the abdomen

may remain soft in the absence of peritonitis. Ecchymosis (bruising) in the

flank or around the um-bilicus may indicate severe pancreatitis. Nausea and

vomiting are common in acute pancreatitis. The emesis is usually gastric in

ori-gin but may also be bile-stained. Fever, jaundice, mental confu-sion, and

agitation also may occur.

Hypotension

is typical and reflects hypovolemia and shock caused by the loss of large

amounts of protein-rich fluid into the tissues and peritoneal cavity. The

patient may develop tachycar-dia, cyanosis, and cold, clammy skin in addition

to hypotension. Acute renal failure is common.

Respiratory distress and hypoxia are common, and the patient may develop diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, dyspnea, tachypnea, and abnormal blood gas values. Myocardial depression, hypocal-cemia, hyperglycemia, and disseminated intravascular coagu-lopathy (DIC) may also occur with acute pancreatitis.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is based on a history of ab-dominal pain, the

presence of known risk factors, physical exam-ination findings, and diagnostic

findings. Serum amylase and lipase levels are used in making the diagnosis of

acute pancreatitis. In 90% of the cases, serum amylase and lipase levels

usually rise in excess of three times their normal upper limit within 24 hours

(Tierney, McPhee & Papadakis, 2001). Serum amylase usually returns to

normal within 48 to 72 hours. Serum lipase levels may remain elevated for 7 to

14 days (Braunwald et al., 2001). Uri-nary amylase levels also become elevated

and remain elevated longer than serum amylase levels. The white blood cell

count is usually elevated; hypocalcemia is present in many patients and correlates

well with the severity of pancreatitis. Transient hyper-glycemia and glucosuria

and elevated serum bilirubin levels occur in some patients with acute

pancreatitis.

X-ray

studies of the abdomen and chest may be obtained to differentiate pancreatitis

from other disorders that may cause sim-ilar symptoms and to detect pleural

effusions. Ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans are used

to iden-tify an increase in the diameter of the pancreas and to detect

pan-creatic cysts, abscesses, or pseudocysts.

Hematocrit

and hemoglobin levels are used to monitor the pa-tient for bleeding. Peritoneal

fluid, obtained through paracente-sis or peritoneal lavage, may contain

increased levels of pancreatic enzymes. The stools of patients with pancreatic

disease are often bulky, pale, and foul-smelling. Fat content of stools varies

between 50% and 90% in pancreatic disease; normally, the fat content is 20%.

ERCP is rarely used in the diagnostic evaluation of acute pancreatitis because

the patient is acutely ill; however, it may be valuable in the treatment of

gallstone pancreatitis.

Medical Management

Management

of the patient with acute pancreatitis is directed to-ward relieving symptoms

and preventing or treating complica-tions. All oral intake is withheld to

inhibit pancreatic stimulation and secretion of pancreatic enzymes. Parenteral

nutrition is usu-ally an important part of therapy, particularly in debilitated

pa-tients, because of the extreme metabolic stress associated with acute

pancreatitis (Dejong, Greve & Soeters, 2001). Nasogastric suction may be

used to relieve nausea and vomiting, to decrease painful abdominal distention

and paralytic ileus, and to remove hydrochloric acid so that it does not enter

the duodenum and stimulate the pancreas. Histamine-2 (H2) antagonists (eg,

ci-metidine [Tagamet] and ranitidine [Zantac]) may be prescribed to decrease

pancreatic activity by inhibiting HCl secretion.

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Adequate

pain medication is essential during the course of acute pancreatitis to provide

sufficient pain relief and minimize rest-lessness, which may stimulate

pancreatic secretion further. Mor-phine and morphine derivatives are often

avoided because it has been thought that they cause spasm of the sphincter of

Oddi; meperidine (Demerol) is often prescribed because it is less likely to

cause spasm of the sphincter (Porth, 2002). Antiemetic agents may be prescribed

to prevent vomiting.

INTENSIVE CARE

Correction

of fluid and blood loss and low albumin levels is nec-essary to maintain fluid

volume and prevent renal failure. The pa-tient is usually acutely ill and is

monitored in the intensive care unit, where hemodynamic monitoring and arterial

blood gas monitoring are initiated. Antibiotic agents may be prescribed if

infection is present; insulin may be required if significant hyper-glycemia

occurs.

RESPIRATORY CARE

Aggressive

respiratory care is indicated because of the high risk for elevation of the

diaphragm, pulmonary infiltrates and effusion, and atelectasis. Hypoxemia

occurs in a significant number of pa-tients with acute pancreatitis even with

normal x-ray findings. Respiratory care may range from close monitoring of

arterial blood gases to use of humidified oxygen to intubation and me-chanical

ventilation.

BILIARY DRAINAGE

Placement

of biliary drains (for external drainage) and stents (in-dwelling tubes) in the

pancreatic duct through endoscopy has been performed to reestablish drainage of

the pancreas. This has resulted in decreased pain and increased weight gain.

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Although

often risky because the acutely ill patient is a poor surgical risk, surgery

may be performed to assist in the diagnosis of pancreatitis (diagnostic

laparotomy), to establish pancreatic drainage, or to resect or débride a

necrotic pancreas. The patient who undergoes pancreatic surgery may have

multiple drains in place postoperatively as well as a surgical incision that is

left open for irrigation and repacking every 2 to 3 days to remove necrotic

debris (Fig. 40-6).

POSTACUTE MANAGEMENT

Antacids

may be used when acute pancreatitis begins to resolve. Oral feedings low in fat

and protein are initiated gradually. Caf-feine and alcohol are eliminated from

the diet. If the episode of pancreatitis occurred during treatment with

thiazide diuretics, corticosteroids, or oral contraceptives, these medications

are dis-continued. Follow-up of the patient may include ultrasound, x-ray

studies, or ERCP to determine whether the pancreatitis is resolv-ing and to assess

for abscesses and pseudocysts. ERCP may also be used to identify the cause of

acute pancreatitis if it is in ques-tion and for endoscopic sphincterotomy and

removal of gall-stones from the common bile duct.

Related Topics