Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Soft anatomy

Alimentary canal of Fishes

Alimentary canal

As in other vertebrates, the alimentary tract can be divided into anterior and posterior regions. The anterior part consists of the mouth, buccal cavity, and pharynx. The posterior part consists of the foregut (esophagus and stomach), midgut or intestine, and hindgut or rectum. Voluntary striated muscle extends from the buccal cavity into the esophagus, involuntary smooth muscle from the posterior portion of the esophagus through the large intestine. Barrington (1957), Kapoor et al. (1975), and Fange and Grove (1979) provide detailed accounts of the alimentary tracts of fishes.

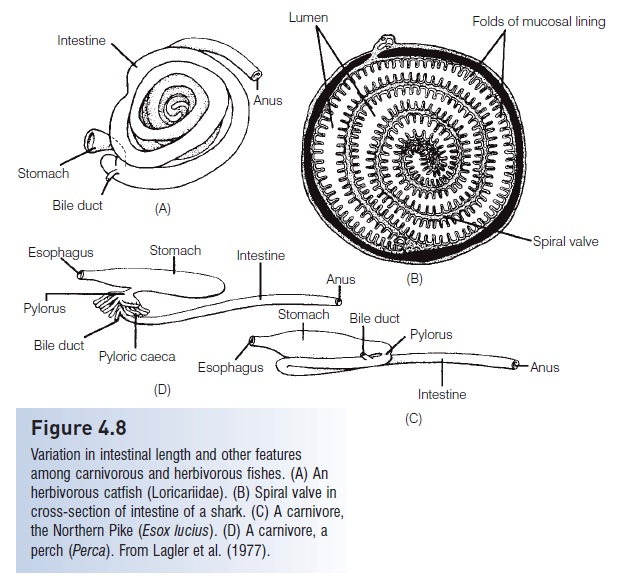

In hagfishes and lampreys, the absence of true jaws is correlated with the absence of a stomach. Presumably, the evolution of jaws permitted capture of larger prey, making a storage organ, the stomach, highly advantageous. Both hagfishes and lampreys have a straight intestine, but the surface area of the intestine is increased in the lampreys by the typhlosole, a fold in the intestinal walls. Chondrichthyes increase the surface area of the intestine by means ofa spiral valve, a sort of a spiral staircase inside the intestine(Fig. 4.8).

Figure 4.8

Variation in intestinal length and other features among carnivorous and herbivorous fishes. (A) An herbivorous catfish (Loricariidae). (B) Spiral valve in cross-section of intestine of a shark. (C) A carnivore, the Northern Pike (Esox lucius). (D) A carnivore, aperch (Perca). From Lagler et al. (1977).

The anatomy of the digestive tract in bony fishes deserves additional description. The buccal cavity (mouth) and pharynx lack the salivary glands present in mammals. These areas are lined with stratified epithelium, mucous cells, and, frequently, taste buds. This area is concerned with seizure, control, and probably also selection of food.

The esophagus is a short, thick-walled tube lined with stratified ciliated epithelium, mucous-secreting goblet cells, and, often, taste buds. The anterior portion has striated muscles, the posterior part smooth muscles that produce peristaltic movement of food toward the stomach. The esophagus is very distensible, so choking is rare, but miscalculation of prey size or armament can lead to the death of the predator, as in the case of a stickleback (Gasterosteidae)becoming stuck in the throat of a pickerel (Esox).

In predaceous fishes, the stomach is lined with columnar epithelium with mucous-secreting cells and one type of glandular cell that produces pepsin and hydrochloric acid. Although usually a fairly simple structure, evolutionary modifications of the fish stomach have led to some unusual functions. For example, the stomach, not the gas bladder, is used for defense by blowfishes and porcupinefishes(Tetraodontidae and Diodontidae), by taking in water or air. The stomach is modified into a grinding organ in sturgeons (Acipenseridae), gizzard shads (Dorosoma),and mullets (Mugilidae) and is used to extract oxygen in some of the South American armored catfishes(Loricariidae).

Many gnathostome fishes lack true stomachs. This is a secondary condition with no simple ecological explanation(Kapoor et al. 1975). Fishes without true stomachs include chimaeras (Holocephali) and lungfishes (Dipnoi). This condition is best documented in the Teleostei, including minnows (Cyprinidae) such as the European Rutilus, killifishes (Cyprinodontidae), wrasses (Labridae; see Chao1973), and parrotfishes (Scaridae). Characteristics of thestomachless condition are both cytological and biochemical. Cytologically, no gastric epithelium or glands arepresent. The stratified epithelium of the esophagus grades into the columnar epithelium of the intestine. Biochemically, no pepsin or hydrochloric acid is produced, making it impossible to dissolve shells or bones.

The intestine of most fishes is lined with simple columnar epithelium and goblet cells. Usually no multicellular glands are present. The chief exception to this is in the cods (Gadidae), which have small tubular glands in the intestinal wall.

Pyloric caeca, finger like pouches that connect to the intestine near the pylorus, are often present. Pyloric caecamay function in absorption or digestion. They vary in number from only three in a scorpionfish (Setarches) to thousands that form a caecal mass in tunas. The number of pyloric caeca is useful in the classification of some groups, like the Salmonidae.

The length of the intestine varies and is generally correlated with feeding habits (see Scavengers,detritivores, and herbivores). Carnivores such as pickerels (Esox)and perches (Perca) have very short intestines, one-third to three-quarters of their body length. The intestine is much longer in herbivores and detritus feeders, 2–20 times the body length. In the herbivorous North American Stoneroller Minnow (Campostoma), the intestine is very longhand wrapped around the swim bladder. The important factor is not only the actual length of the intestine but alsothe internal surface area of the intestinal mucosa. In additionto sharks, as mentioned earlier, some primitive bonyfishes such as the Coelacanths (Latimeria), lungfishes, gars,and Ladyfish (Elops) have a spiral valve intestine that increases the surface area internally (see Fig. 4.8).

The hindgut or rectum is not as well defined externally in fishes as it is in tetrapod’s. Generally, the muscle layer near the rectum is thicker than in anterior regions, and the number of goblet cells in the large intestine increases in the rectal region. In Chondrichthyes, the hindgut is lined with stratified epithelium, contrasting with a single cell layer inthe midgut. An iliocaecal valve between the small and large intestines is often found in teleost`s, but this valve is absent in Chondrichthyes, Dipnoi, and Polypterus.

The liver and pancreas both participate in digestion. The liver develops as a ventral evagination of the intestine, asin other vertebrates. The anterior portion develops into the liver proper, and the posterior portion into the gallbladder and bile duct. The liver also stores fat in some fishes. Before vitamins A and D were synthesized, cods and sharks were harvested for their liver oil, which is rich in these vitamins. The gallbladder is a thin-walled temporary storage organ for the bile. It empties into the intestine near the pylorus by contraction of smooth muscles. Bile is usually green due to bile pigments (biliverdin and bilirubin) resulting from the breakdown of blood cells and hemoglobin, and also contains fat-emulsifying bile salts, which may assist in converting the acidity of the stomach to the neutral conditions in the intestine. The pancreas is both an endocrine organand an exocrine organ that produces digestive enzymes. These enzymes include proteases such as trypsin, carbohydrase such as amylase and lipase, and, in some insect feeding fishes, chitinase. The pancreas is a compact, often two-lobed structure in Chondrichthyes, is distinct in softrayedteleost`s, but becomes incorporated into the liver as a hepatopancreas in most spiny-rayed teleost`s (except for parrotfishes). The anatomically and histologically diffuse nature of the pancreas makes it difficult to study pancreatic function in these advanced fishes.

The various parts of the alimentary tract work together in conjunction with the feeding habits of a fish. For example,de Groot (1971) presented an instructive comparison of correlations between various organ systems and feeding in three families of flatfishes. The Bothidae, which are diurnal carnivores, possess a single loop of the intestine, heavily toothed gill rakers, small olfactory lobes of the brain, and large optic lobes. The Pleuronectidae are also diurnal but have complex loops of the intestine, less toothed gill rakers, medium olfactory lobes, and large optic lobes. The Soleidae,which are nocturnal feeders, have more complex intestinal loops, few gill raker teeth, large olfactory lobes, and small optic lobes.

Related Topics