Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Drug Absorption and Distribution

Absorption of Drugs From the Alimentary Tract

ABSORPTION OF

DRUGS FROM THE ALIMENTARY TRACT

Oral Cavity and Sublingual Absorption

In contrast to absorption

from the stomach and intes-tine, drugs absorbed from the oral cavity enter the

gen-eral circulation directly. Although the surface area of the oral cavity is

small, absorption can be rapid if the drug has a high lipid–water partition

coefficient and therefore can readily diffuse through lipid membranes. Since

the diffusion process is very rapid for un-ionized drugs, pKa will be a major determinant

of the lipid– water partition coefficient for a particular therapeutic agent.

For instance, the weak base nicotine (pKa

8.5) reaches peak blood levels four times faster when ab-sorbed from the mouth

(pH 6), where 40 to 50% of the drug is in the un-ionized form, than from the

gastroin-testinal tract (pH 1–5), where the drug exists mainly in its ionized

(protonated) form.

Although the oral mucosa is

highly vascularized and its epithelial lining is quite thin, drug absorption

from the oral cavity is limited. This is due in part to the rela-tively slow

dissolution rate of most solid dosage forms and in part to the difficulty in

keeping dissolved drug in contact with the oral mucosa for a sufficient length

of time. These difficulties may be overcome if the drug is placed under the

tongue (sublingual administration) or between the cheek and gum (buccal cavity)

in a formu-lation that allows rapid tablet dissolution in salivary se-cretions.

The extensive network of blood vessels facili-tates rapid drug absorption.

Sublingual administration is the route of choice for a drug like nitroglycerin

(glyc-eryl trinitrate), whose coronary vasodilator effects are required quickly

in cases of angina. Furthermore, if swallowed, the drug would be absorbed from

the gas-trointestinal tract and carried to the liver, where nitro-glycerin is

subject to rapid metabolism and inactivation.

Absorption from the Stomach

Although the primary function of the stomach is not ab-sorption, its rich

blood supply and the contact of its con-tents with the epithelial lining of the

gastric mucosa provide a potential site for drug absorption. However, since

stomach emptying time can be altered by many variables (e.g., volume of

ingested material, type and viscosity of the ingested meal, body position,

psycholog-ical state), the extent of gastric absorption will vary from patient

to patient as well as at different times within a single individual.

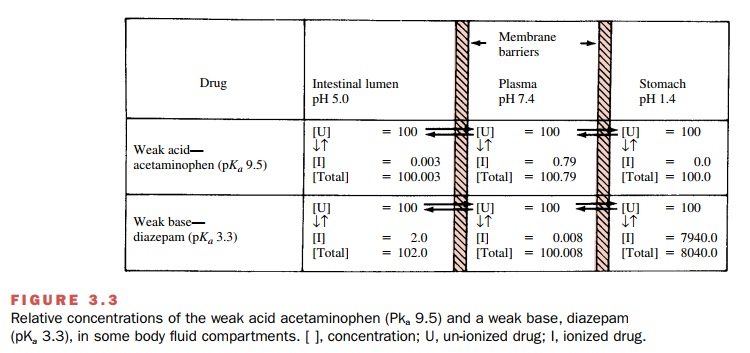

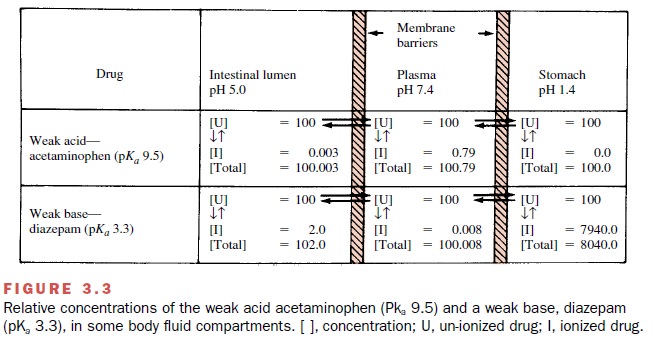

The low pH of the gastric

contents (pH 1–2) may have consequences for absorption because it can

dra-matically affect the degree of drug ionization. For ex-ample, the weak base

diazepam (pKa 3.3) will be

highly protonated in the gastric juice, and consequently, ab- sorption across

lipid membranes of the stomach will be particularly slow. On the other hand,

the weak acid acetaminophen (pKa

9.5) will exist mainly in its un-ionized form and can more readily diffuse from

the stomach into the systemic circulation (Fig. 3.3).

Because of the influence of

pH on ionization of weak bases, basic drugs may be trapped in the stomach even

if they are administered intravenously. Since basic compounds exist primarily

in their un-ionized form in the blood (pH 7.4), they readily diffuse from the

blood into the gastric juice. Once in contact with the gastric contents (pH

1–2), they will ionize rapidly, which re-stricts their diffusibility. At

equilibrium, the concentra-tion of the un-ionized lipid-soluble fraction will

be iden-tical on both sides of the gastric membranes, but there will be more total basic drug on the side where

ioniza-tion is greatest (i.e., in gastric contents). This means of drug

accumulation is called ion trapping.

Absorption from the Small Intestine

The epithelial lining of the

small intestine is composed of a single layer of cells called enterocytes. It

consists of many villi and microvilli and has a complex supply of blood and

lymphatic vessels into which digested food and drugs are absorbed. The small

intestine, with its large surface area and high blood perfusion rate, has a

greater capacity for absorption than does the stomach. Most drug absorption occurs in the proximal jejunum (first 1–2 m in

humans).

Although transfer of drugs

across the intestinal wall can occur by facilitated transport, active

transport, en-docytosis, and filtration, the predominant process for most drugs

is diffusion. Thus, the pKa

of the drug and the pH of the intestinal fluid (pH 5) will strongly influ-ence

the rate of drug absorption. While weak acids like phenobarbital (pKa 7.4) can be absorbed from

the stom-ach, they are more readily absorbed from the small in-testine because

of the latter’s extensive surface area.

Conditions that shorten

intestinal transit time (e.g., diarrhea) decrease intestinal drug absorption,

while in-creases in transit time will enhance intestinal absorption by

permitting drugs to remain in contact with the intes-tinal mucosa longer.

Although delays in gastric empty-ing time will increase gastric drug

absorption, in gen-eral, total drug

absorption may actually decrease, since material will not be transferred to the

large absorptive surface of the small intestine.

Absorption from the Large Intestine

The large intestine has a

considerably smaller absorp-tive surface area than the small intestine, but it

may still serve as a site of drug absorption, especially for com-pounds that

have not been completely absorbed from the small intestine. However, little

absorption occurs from this site, since the relatively solid nature of the

in-testinal contents impedes diffusion of the drug from the contents to the mucosa.

The most distal portion of

the large intestine, the rectum, can be used directly as a site of drug

adminis-tration. This route is especially useful where the drug may cause

gastric irritation, after gastrointestinal sur-gery, during protracted

vomiting, and in uncooperative patients (e.g., children) or unconscious ones.

Dosage forms include solutions and suppositories. The processes involved in rectal

absorption are similar to those de-scribed for other sites.

Although the surface area

available for absorption is not large, absorption can still occur, owing to the

ex-tensive vascularity of the rectal mucosa. Drugs ab-sorbed from the rectum

largely escape the biotransfor-mation to which orally administered drugs are

subject, because a portion of the blood

that perfuses the rectum is not

delivered directly to the liver, and therefore, rectally administered drug, at

least in part, escapes hepatic first-pass metabolism.

Related Topics