Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Patients With Allergic Disorders

Allergic Rhinitis - Allergic Disorders

ALLERGIC

RHINITIS

Allergic

rhinitis (inflammation of nasal

mucosa; hay fever, chronic allergic rhinitis, pollinosis) is the most common

form of respiratory allergy presumed to be mediated by an immediate (type I

hypersensitivity) immunologic reaction. It affects about 8% to 10% of the U.S.

population (20% to 30% of adolescents). The symptoms are similar to viral

rhinitis but are usually more persistent and demonstrate seasonal variation

(Tierney, McPhee Papadakis, 2001). It often occurs with other conditions, such

as allergic conjunctivitis, sinusitis, and asthma. Allergic rhinitis is

associated with impaired work and school performance and de-creased quality of

life (Ratner, Ehrlich, Fineman et al., 2002). When untreated, many

complications may result, such as allergic asthma, chronic nasal obstruction,

chronic otitis media with hear-ing loss, anosmia (absence of the sense of

smell), and, in children, orofacial dental deformities. Early diagnosis and

adequate treat-ment are essential to reduce complications and relieve symptoms.

Because

allergic rhinitis is induced by airborne pollens or molds, it is characterized

by the following seasonal occurrences:

· Early spring—tree pollen

(oak, elm, poplar)

· Early summer—rose pollen

(rose fever), grass pollen (Timothy, red-top)

· Early fall—weed pollen

(ragweed)

Each

year, attacks begin and end at about the same time. Air-borne mold spores

require warm, damp weather. Although there is no rigid seasonal pattern, these

spores appear in early spring, are rampant during the summer, and taper off and

disappear by the first frost.

Pathophysiology

Sensitization begins by ingestion or inhalation of an antigen. On re-exposure, the nasal mucosa reacts by the slowing of ciliary ac-tion, edema formation, and leukocyte (primarily eosinophil) in-filtration. Histamine is the major mediator of allergic reactions in the nasal mucosa. Tissue edema results from vasodilation and increased capillary permeability.

Clinical Manifestations

Typical signs and symptoms of allergic

rhinitis include nasal con-gestion; clear, watery nasal discharge; intermittent

sneezing; and nasal itching. Itching of the throat and soft palate is common.

Drainage of nasal mucus into the pharynx initiates multiple at-tempts to clear

the throat and results in a dry cough or hoarseness. Headache, pain over the

paranasal sinuses, and epistaxis can ac-company allergic rhinitis. The symptoms

of this chronic condition depend on environmental exposure and intrinsic host

responsive-ness. Allergic rhinitis may affect quality of life by also producing

fatigue,

loss of sleep, and poor concentration (Ratner et al., 2002).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnosis of seasonal allergic rhinitis is

based on history, physi-cal examination, and diagnostic test results.

Diagnostic tests in-clude nasal smears, peripheral blood counts, total serum

IgE, epicutaneous and intradermal testing, RAST, food elimination and

challenge, and nasal provocation tests. Results indicative of allergy as the

cause of rhinitis include increased IgE and eosinophil levels and positive

reactions on allergen testing. False-positive and false-negative responses to

these tests, particularly skin testing and provocation tests, may occur.

Medical Management

The goal of therapy is to provide relief from

symptoms. Therapy may include one or all of the following interventions:

avoidance therapy, pharmacotherapy, and immunotherapy (Kay, 2001b). Verbal

instructions must be reinforced by written information. Knowledge of general

concepts regarding assessment and therapy in allergic diseases is important so

that patients can learn to manage certain conditions as well as prevent severe

reactions and illnesses.

AVOIDANCE THERAPY

In avoidance therapy, every attempt is made

to remove the aller-gens that act as precipitating factors. Simple measures and

envi-ronmental controls are often effective in decreasing symptoms. Examples

include use of air conditioners, air cleaners, humidifiers and dehumidifiers,

and smoke-free environments. In many cases, it is impossible to avoid exposure

to all environmental allergens, so pharmacologic therapy or immunotherapy is

needed.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Antihistamines.

Antihistamines,

now classified as H1-receptorantagonists (or H1-blockers),

are used in managing mild allergic disorders. (H2-receptor antagonists are used to

treat gastric and duodenal ulcers.) H1-blockers bind selectively to H1 receptors,

preventing the actions of histamines at these sites. They do not prevent the

release of histamine from mast cells or basophils. The H1-antagonists

have no effect on H2-receptors, but they do have the

ability to bind to nonhistaminic receptors. The ability of cer-tain

antihistamines to bind to and block muscarinic receptors un-derlies several of

the prominent anticholinergic side effects of these medications.

Oral antihistamines, which are readily

absorbed, are most ef-fective when given at the first occurrence of symptoms

because they prevent the development of new symptoms by blocking the actions of

histamine at the H1-receptors. The effectiveness of these medications is limited to certain

patients with hay fever, va-somotor rhinitis, urticaria (hives), and mild asthma. They are rarely effective in

other conditions or in any severe conditions.Antihistamines are the major class of

medications prescribed for the symptomatic relief of allergic rhinitis. The

major side ef-fect is sedation, although histamine H1 antagonists are less

sedat-ing than earlier antihistamines (Kay, 2001b). Additional side effects

include nervousness, tremors, dizziness, dry mouth, palpi-tations, anorexia,

nausea, and vomiting. Antihistamines are con-traindicated during the third

trimester of pregnancy; for nursing mothers and newborns; in children and

elderly people; and in pa-tients whose conditions can be aggravated by

muscarinic blockade (ie, asthma, urinary retention, open-angle glaucoma,

hyperten-sion, and prostatic hyperplasia).

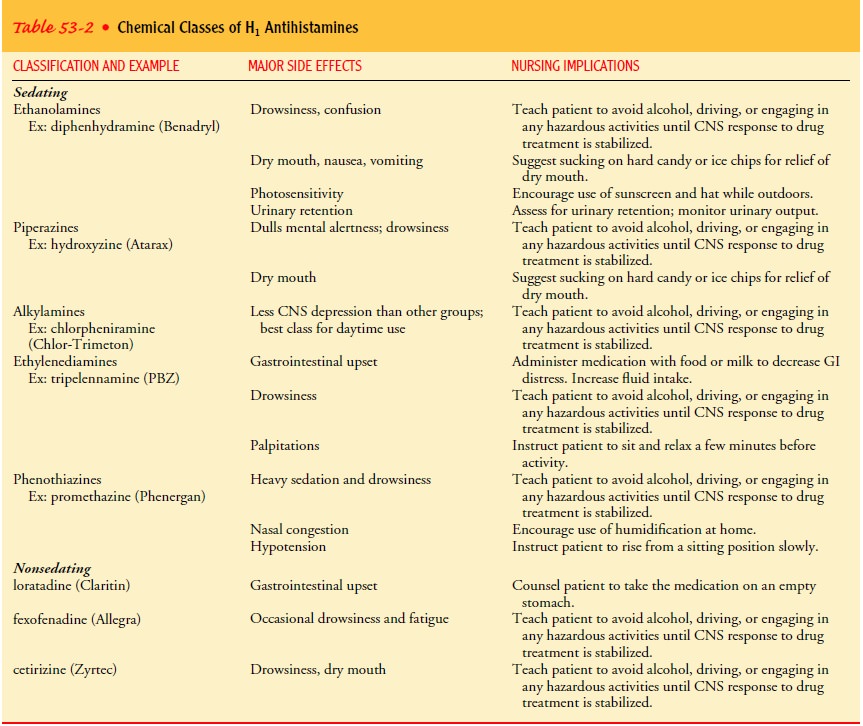

Newer

antihistamines are called second-generation or non-sedating H1-receptor antagonists.

Unlike first-generation H1-receptor antagonists, they do not cross the

blood–brain barrier and do not bind to cholinergic, serotonin, or

alpha-adrenergic re-ceptors. They bind to peripheral rather than central

nervous sys-tem H1-receptors, causing less sedation. Examples of

these medications are loratadine (Claritin), cetirizine (Zyrtec), and

fex-ofenadine (Allegra). These are summarized in Table 53-2.tion to the oral

route. The topical route (drops and sprays) causes fewer side effects than oral

administration; however, the use of drops and sprays should be limited to a few

days to avoid rebound congestion. Adrenergic nasal decongestants are used for

the relief of nasal congestion when applied topically to the nasal mucosa. They

activate the alpha-adrenergic receptor sites on the smooth muscle of the nasal

mucosal blood vessels, reducing local blood flow, fluid exudation, and mucosal

edema. Topical ophthalmic drops are used for symptomatic relief of eye

irritations due to al-lergies. Potential side effects include hypertension,

dysrhythmias, palpitations, central nervous system stimulation, irritability,

tremor, and tachyphylaxis (acceleration of hemodynamic status). Examples of

adrenergic decongestants and their routes of admin-istration are found in Table

53-3.

Mast Cell Stabilizers.

Intranasal cromolyn sodium (Nasalcrom)is a spray that acts by

stabilizing the mast cell membrane, thus re-ducing the release of histamine and

other mediators of the aller-gic response. In addition, it inhibits

macrophages, eosinophils, monocytes, and platelets involved in the immune

response (Ratner et al., 2002). Cromolyn interrupts the physiologic response to

nasal antigens and is used prophylactically before exposure to

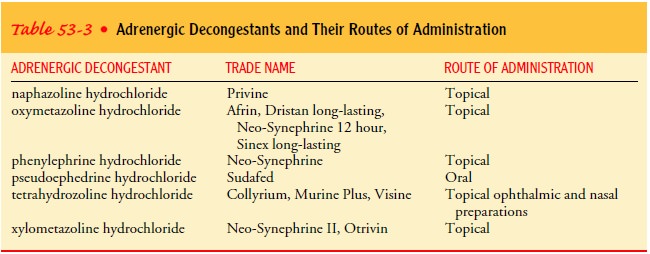

Adrenergic Agents.

Adrenergic agents, vasoconstrictors of mu-cosal vessels, are used

topically (nasal and ophthalmic) in addition to the oral route. The topical route

(drops and sprays) causes fewer side effects than oral administration; however,

the use of drops and sprays should be limited to a few days to avoid rebound

congestion. Adrenergic nasal decongestants are used for the relief of nasal

congestion when applied topically to the nasal mucosa. They activate the

alpha-adrenergic receptor sites on the smooth muscle of the nasal mucosal blood

vessels, reducing local blood flow, fluid exudation, and mucosal edema. Topical

ophthalmic drops are used for symptomatic relief of eye irritations due to

al-lergies. Potential side effects include hypertension, dysrhythmias,

palpitations, central nervous system stimulation, irritability, tremor, and

tachyphylaxis (acceleration of hemodynamic status). Examples of adrenergic

decongestants and their routes of admin-istration are found in Table 53-3.

Mast Cell Stabilizers.

Intranasal cromolyn sodium (Nasalcrom)is a spray that acts by stabilizing the mast cell membrane, thus re-ducing the release of histamine and other mediators of the aller-gic response. In addition, it inhibits macrophages, eosinophils, monocytes, and platelets involved in the immune response (Ratner et al., 2002). Cromolyn interrupts the physiologic response to nasal antigens and is used prophylactically before exposure to allergens to prevent the onset of symptoms and to treat symptoms once they occur.

It is also used therapeutically in

chronic allergic rhinitis. This spray is as effective as antihistamines but

less effec-tive than intranasal corticosteroids in the treatment of seasonal

allergic rhinitis. Patients must be informed that the beneficial ef-fects of

the medication may take a week or so to occur. The med-ication is of no benefit

in the treatment of nonallergic rhinitis. Adverse effects (ie, sneezing, local

stinging, and burning sensa-tions) are usually mild.

Corticosteroids.

Intranasal corticosteroids are indicated in moresevere cases of allergic

and perennial rhinitis that cannot be con-trolled by more conventional

medications such as decongestants, antihistamines, and intranasal cromolyn.

These medications include beclomethasone (Beconase, Vancenase), budesonide

(Rhinocort), dexamethasone (Decadron Phosphate Turbinaire), flunisolide

(Nasalide), fluticasone (Cutivate, Flonase), and tri-amcinolone (Nasacort).

Because of their anti-inflammatory actions,

these medications are equally effective in preventing or suppressing the major

symp-toms of allergic rhinitis. Corticosteroids are administered by

metered-spray devices. If the nasal passages are blocked, a topical

decongestant can be used to clear the passages before the adminis-tration of

the intranasal corticosteroid. Patients must be aware that full benefit may not

be achieved for several days to 2 weeks. Ad-verse effects of intranasal

corticosteroids are mild and include dry-ing of the nasal mucosa and burning

and itching sensations caused by the vehicle used to administer the medication.

Systemic effects are more likely with dexamethasone. Recommended use of this

medication is limited to 30 days. Beclomethasone, budesonide, flu-nisolide,

fluticasone, and triamcinolone are deactivated rapidly after absorption, so

they do not achieve significant blood levels. Corticosteroids suppress host

defenses, so they must be used with caution in patients with tuberculosis or

untreated bacterial infec-tions of the lungs. Patients on corticosteroids are

at risk for infec-tion and for suppression of typical manifestations of

inflammation because host defenses are compromised. Inhaled corticosteroids do

not affect the immune system to the same degree as systemic cor-ticosteroids

(ie, oral corticosteroids). As corticosteroids are inhaled into the upper

respiratory tract, tuberculosis or untreated bacte-rial infections of the lungs

may become apparent and progress. Whenever possible, patients with tuberculosis

and other bacterial infections of the lungs should avoid inhaled

corticosteroids.

Oral and parenteral corticosteroids are used

when conven-tional therapy has failed and symptoms are severe and of short

du-ration. They can control symptoms of allergic reactions such as hay fever,

medication-induced allergies, and allergic reactions toinsect stings. Because

the response to corticosteroids is delayed, they have little or no value in

acute therapy for severe reactions such as anaphylaxis. Patients who receive

corticosteroids must be cautioned not to stop taking the medication suddenly or

without specific instructions from the physician. The patient is also

in-structed about side effects, which include fluid retention, weight gain,

hypertension, gastric irritation, glucose intolerance, and adrenal suppression.

IMMUNOTHERAPY

Allergen desensitization (allergen

immunotherapy, hyposensitiza-tion) is primarily used to treat IgE-mediated

diseases by injections of allergen extracts. This type of therapy provides an

adjunct to symptomatic pharmacologic therapy and can be used when aller-gen

avoidance is not possible (Parslow et al., 2001). Specific im-munotherapy has

been used in the treatment of allergic disorders for about 100 years. It

consists of administering increasing con-centrations of extracts of specific

allergens over a long period (Kay, 2001b). Goals of immunotherapy include

reducing the level of circulating IgE, increasing the level of blocking

antibody IgG, and reducing mediator cell sensitivity. Immunotherapy has been

most effective for ragweed pollen; however, treatment for grass, tree pollen,

cat, and house dust mite allergens has also been effective.

Correlation of a positive skin test with a

positive allergy his-tory is an indication for immunotherapy if the allergen

cannot be avoided. The value has been fairly well established in instances of

allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma that are clearly due to sen-sitivity to

one of the common pollens, molds, and household dust. Although helpful in most

patients, immunotherapy does not cure the condition. Before immunotherapy is

initiated, the patient must understand what to expect and the importance of

continuing therapy for several years. When skin tests are per-formed, the

results are correlated with clinical manifestations; treatment is based on the

patient’s needs rather than on skin tests.

The most common method of treatment is the

serial injection of one or more antigens that are selected in each particular

case on the basis of skin tests. This method provides a simple and ef-ficient

technique for identifying IgE antibodies to specific anti-gens. Specific

treatment consists of injecting extracts of the pollens or mold spores that

cause symptoms in a particular pa-tient. Injections begin with very small amounts

and are gradually increased, usually at weekly intervals, until a maximum

tolerated dose is attained. Maintenance booster injections are given at 2- to

4-week intervals, frequently for a period of several years, before maximum

benefit is achieved There are three methods of injection therapy: coseasonal,

pre-seasonal, and perennial. When treatment is given on a coseasonal basis,

therapy is initiated during the season in which the patient experiences

symptoms. This method has been proved ineffective and is used infrequently.

Also, there is an increased risk of sys-temic reactions. Preseasonal therapy

injections are given 2 to 3 months before symptoms are expected, allowing time

for hypo-sensitization to occur. This treatment is discontinued after the

season begins. Perennial therapy is administered all year round, usually on a

monthly basis, and is the preferred method because it has more effective,

longer-lasting results.

Any

patient who receives specific immunotherapy is at risk for general, and

potentially fatal, anaphylaxis. This occurs most fre-quently at the induction

or “up-dosing” phase. Attempts have been made to minimize the risk of systemic

reactions by pre-treating allergen extracts with agents such as formaldehyde.

This approach decreases the binding of the allergen by IgE, but it also results

in decreased immunogenicity (Kay, 2001b).

Because of the risk for anaphylaxis,

injections should not be given by a lay person or by the patient. The patient

remains in the office or clinic for at least 30 minutes after the injection and

is ob-served for possible systemic symptoms. If a large, local swelling

de-velops at the injection site, the next dose should not be increased, because

this may be a warning sign of a possible systemic reaction.

Therapeutic

failure is evident when a patient does not experi-ence a decrease of symptoms

within 12 to 24 months, fails to de-velop increased tolerance to known

allergens, and cannot decrease the use of medications to reduce symptoms.

Potential causes of treatment failure include misdiagnosis of allergies,

inadequate doses of allergen, newly developed allergies, and inadequate

en-vironmental controls.

Related Topics