Rise of Nationalism in India | History - Western Education and its Impact | 12th History : Chapter 1 : Rise of Nationalism in India

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 1 : Rise of Nationalism in India

Western Education and its Impact

Western Education and its Impact

(a) Education in Pre-British India

Education

in pre-colonial India was characterised by segmentation along religious and

caste lines. Among the Hindus, Brahmins had the exclusive privilege to acquire

higher religious and philosophical knowledge. They monopolised the education

system and occupied positions in the society, primarily as priests and

teachers. They studied in special seminaries such as Vidyalayas and Chatuspathis.

The medium of instruction was Sanskrit, which was considered as the sacred

language. Technical knowledge – especially in relation to architecture,

metallurgy, etc. – was passed hereditarily. This came in the way of innovation.

Another shortcoming of this system was that it barred women, lower castes and

other under-privileged people from accessing education. The emphasis on rote

learning was another impediment to innovation.

(b) Contribution of Colonial State: Macaulay System of Education

The

colonial government aided the spread of modern education in India for a

different reason than educating and empowering the Indians. To administer a

large colony like India, the British needed a large number of personnel to work

for them. It was impossible for the British to import the educated lot, needed

in such large numbers, from Britain. With this aim, the English Education Act

was passed by the Council of India in 1835. T.B. Macaulay drafted this system

of education introduced in India. Consequently, the colonial administration

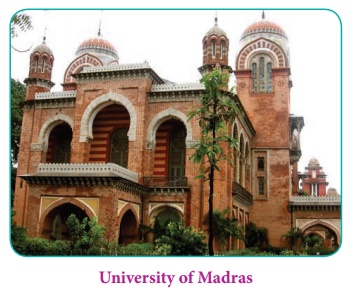

started schools, colleges and universities, imparting English and modern

education, in India. Universities were established in Bombay, Madras and

Calcutta in 1857. The colonial government expected this section of educated

Indians to be loyal to the British and act as the pillars of the British Raj.

T. B. Macaulay was India’s first law member of the Governor

General in Council from 1834 to 1838. Before Macaulay arrived in India the General

Committee of Public Instruction was formed in 1823 with the responsibility to

guide the East India Company on the matter of education and the medium of

instruction. The Committee was split into two groups. The Orientalist group

advocated education in vernacular languages. The Anglicists advocated Western

education in English.

Macaulay was on the side of Anglicists and wrote his famous ‘Minute on Indian Education’ in 1835. In this Minute, he argued for Western education in the English language. His intention behind supporting the Anglicists was that he wanted to create a class of persons from within India who would 'be Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals and in intellect'.

The

British created an educated Indian middle class for their own ends but sneered

at it as the Babu class. That very class, however, became the progressive

intelligentsia of India and played a leading role in mobilising the people for

the liberation of the country.

(c) Role of Educated Middle Class

The

economic and administrative transformation on the one side and the growth of

Western education on the other gave the space for the growth of new social

classes. From within these social classes, a modern Indian intelligentsia

emerged. The “neo-social classes” created by the British Raj, which included

the Indian trading and business communities, landlords, money lenders,

English-educated Indians employed in imperial subordinate services, lawyers and

doctors, initially adopted a positive approach towards the colonial

administration. However, soon they realised that their interests would be

better served only in independent India. People of the said social classes

began to play a prominent role in promoting patriotism amongst the people. The

consciousness of these classes found articulation in a number of associations

prior to the founding of the Indian National Congress at the national level.

Raja Ram

Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Swami Vivekananda, Aurobindo Ghose,

Gopala Krishna Gokhale, Dadabhai Naoroji, Feroz Shah Mehta, Surendra Nath

Banerjea and others who belonged to modern Indian intelligentsia led the

social, religious and political movements in India. Educated Indians had

exposure to ideas of nationalism, democracy, socialism, etc. articulated by

John Locke, James Stuart Mill, Mazzini, Garibaldi, Rousseau, Thomas Paine, Marx

and other western intellectuals. The right of a free press, the right of free

speech and the right of association were the three inherent rights, which their

European counterparts held dear to their heart, and the educated Indians too

desired to cling to. Various forums came into existence, where people could

meet and discuss the issues affecting their interests. This became possible now

at the national level, due to the rapid expansion of transport network and

establishment of postal, telegraph and wireless services all over India.

(d) Contribution of Missionaries

One of

the earliest initiatives to impart modern education among Indians was taken up

by the Christian missionaries. Inspired by the proselytizing sprit, they

attacked polytheism and caste inequalities that were prevalent among the

Hindus. One of the methods adopted by the missionaries, to preach Christianity,

was through modern secular education. They provided opportunities to acquire

education to the underprivileged and the marginalised sections, who were denied

learning opportunities in the traditional education system. However only a very

small fraction converted to Christianity. But the challenge posed by

Christianity led to various social and religious reform movements.

Related Topics