Rise of Nationalism in India | History - Socio-economic Background | 12th History : Chapter 1 : Rise of Nationalism in India

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 1 : Rise of Nationalism in India

Socio-economic Background

Socio-economic Background

(a) Implications of the New Land Tenures

The

British destroyed the traditional basis of Indian land system. In the

pre-British days, the land revenue was realised by sharing the actual crop with

the cultivators. The British fixed the land revenue in cash without any regard

to various contingencies, such as failure of crops, fall in prices and droughts

or floods. Moreover, the practice of sale in settlement of debt encouraged

money lenders to advance money to landholders and resorting to every kind of

trickery to rob them of their property.

There

were also two other major implications of the new land settlements introduced

by the East India Company. They institutionalised the commodification of land

and commercialisation of agriculture in India. As mentioned earlier, there was

no private property in land in pre-British era. Now, land became a commodity

that could be transferred either by way of buying and selling or by way of the

administration taking over land from holders, in lieu of default on payment of

tax/rent. Land taken over in such cases was auctioned off to another bidder.

This created a new class of absentee landlords who lived in the cities and

extracted revenue from the lands without actually living on the lands. In the

traditional agricultural set-up, the villagers produced largely for their

consumption among themselves. After the new land settlements, agricultural

produce was predominantly for the market.

The

commodification of land and commercialisation of agriculture did not improve

the lives and conditions of the peasants. Instead, this created discontent

among the peasantry and made them restive. These peasants later on turned

against the imperialists and their collaborators.

(b) Laissez Faire Policy and De-industrialization: Impact on Indian Artisans

The

policy of the Company in the wake of Industrial Revolution in England resulted

in the de-industrialization of India. This continued until the beginning of the

World War I. The British Government pursued a policy of free trade or laissez faire. Raw materials like

cotton, jute and silks from India were taken to Britain.

The

finished products made from those raw materials were then transported back to

the Indian markets. Mass production with the help of technological advancement

enabled them to flood the Indian market with their goods. It was available at a

comparatively cheaper price than the Indian handloom cloth. Prior to the arrival

of the British, India was known for its handloom products and handicrafts. It

commanded a good world market. However, as a result of the colonial policy,

gradually Indian handloom products and handicrafts lost there market, domestic

as well as international. Import of English articles into India threw the

weavers, the cotton dressers, the carpenters, the blacksmiths and the

shoemakers out of employment. India became a procurement area for the raw

material and the farmers were forced to produce industrial crops like indigo

and other cash crops like cotton for use in British factories. Due to this

shift, subsistence agriculture, which was the mainstay for several hundred

years, suffered leading to food scarcity.

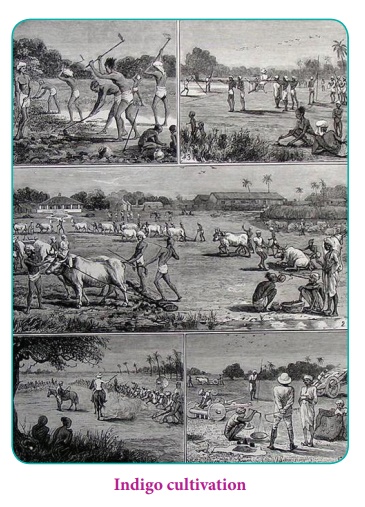

The

Indigo revolt of 1859 – 60 in Bengal was one of the responses from the Indian

farmer to the oppressive policy of the British. Indian tenants were forced to

grow indigo by their planters who were mostly Europeans. Used to dye the

clothes indigo was in high demand in Europe. Peasants were forced to accept

meagre amounts as advance and enter into unfair contracts. Once a peasant

accepted the contract, he had no option but to grow indigo on his land. The

price paid by the planter was far lower than the market price. Many a times,

the peasants could not even pay their land revenue dues. Hoping that the

authorities would address their concerns, the peasants wrote several petitions

to authorities and organised peaceful protests. As their plea for reform went

in vain, they revolted by refusing to accept any further advances and enter

into new contracts. Peasants, through the Indigo revolt of 1859-60, were able

to force the planters to withdraw from northern-Bengal.

(c) Famines and Emigration of Indians to Overseas British Colonies

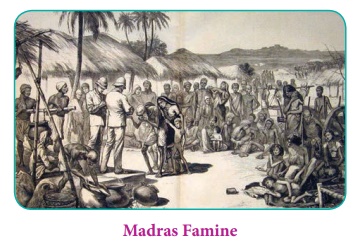

Famines

As India

became increasingly de-industrialised and weavers and artisans engaged in

handicrafts were thrown out of employment, there were recurrent famines due to

the neglect of irrigation and oppressive taxation on land. Before the arrival

of the British, Indian rulers had ameliorated the difficulties of the populace

in times of famines by providing tax relief, regulating the grain prices and

banning food exports from famine-hit areas. But the British extended their

policy of non-intervention (laissez faire) even to famines. As a result,

millions of people died of starvation during the Raj. It has been estimated

that between 1770 and 1900, twenty five million Indians died in famines.

William Digby, the editor of Madras Times, pointed out that during 1793-1900

alone an estimated five million

people had died in all the wars around the world, whereas in just ten years

(1891-1900), nineteen million had died in India in famines alone.

Sadly

when people were dying of starvation millions of tonnes of wheat was exported to Britain. During the 1866

Orissa Famine, for instance, while a million and a half people starved to

death, the British exported 200 million pounds of rice to Britain. The Orissa

Famine prompted nationalist Dadabhai Naoroji to begin his lifelong

investigations into Indian poverty. The failure of two successive monsoons

caused a severe famine in the Madras Presidency during 1876-78. The viceroy

Lytton adopted a hands-off approach similar to that followed in Orissa. An

estimated 3.5 million people died in the Madras presidency.

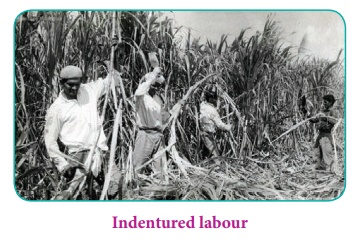

Indentured

Labour

The

introduction of plantation crops such as coffee, tea and sugar in Empire

colonies such as Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Mauritius, Fiji, Malaya, the Caribbean

islands, and South Africa required enormous labour. In 1815, the Governor of

Madras received a communication from the Governor of Ceylon asking for

“coolies” to work on the coffee plantations. The Madras Governor forwarded this

letter to the collector of Thanjavur, who reported that the people were very

much attached to the soil and unless some incentive was provided it was not

easy to make them move out of their native soil. But the outbreak of two

famines (1833 and 1843) forced the people, without any incentive from the government,

to leave for Ceylon to work as coolies in coffee and tea plantations under the

indentured labour system. The abolition of slavery in British India in 1843

also facilitated the processes of emigration to Empire colonies. In 1837 the

number of immigrant Tamil labourers employed in Ceylon coffee estate was

estimated at 10,000. The industry developed rapidly and so did the demand for

Tamil labour. In 1846 its presence was estimated at 80,000 and in 1855 at

128,000 persons. In 1877, the famine year, there were nearly 380,000 Tamil

labourers in Ceylon.

Besides

Ceylon, many Indians opted to emigrate as indentured labour to other British

colonies such as Mauritius, Straits Settlements, Caribbean islands, Trinidad,

Fiji and South Africa. In 1843 it was officially reported that 30,218 male and

4,307 females had entered Mauritius as indentured labourers. By the end of the

century some 5,00,000 labourers had moved from India to Mauritius.

Indentured Labour: Under this penal contract

system (indenture), labourers were hired for a period of five years and

they could return to their homeland with passage paid at the end. Many

impoverished peasants and weavers went hoping to earn some money. It turned out

to be as worse than slave labour. The colonial state allowed agents (kanganis) to trick or kidnap indigent

landless labourers. The labourers suffered terribly on the long sea voyages and

many died on the way. The percentage of deaths of indentured labour during

1856-57, in a ship bound for Trinidad from Kolkata is as follows: 12.3% of all

males, 18.5% of the females, 28% of the boys 36% of the girls and 55% of the

infants perished.

Related Topics