Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Reactive erythemas and vasculitis

Urticaria (hives, ‘nettle-rash’)

Urticaria

(hives, ‘nettle-rash’)

Urticaria

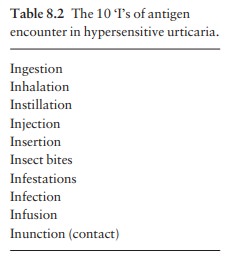

is a common reaction pattern in which pink, itchy or ‘burning’ swellings

(wheals) can occur any-where on the body. Individual wheals do not last longer

Traditionally, urticaria is divided into acute and chronic forms, based on the

duration of the disease rather than of individual wheals. Urticaria that

persists for more than 6 weeks is clas-sified as chronic. Most patients with

chronic urticaria, other than those with an obvious physical cause, have what

is often known as ‘ordinary urticaria’.

Cause

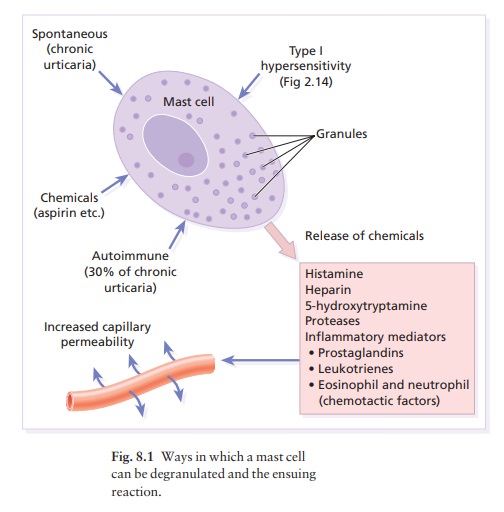

The signs and symptoms of urticaria are caused by mast cell degranulation, with release of histamine (Fig. 8.1).

The mechanisms underlying this may be different

but the end result, increased capillary per-meability leading to transient

leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissue and development of a wheal, is the

same (Fig. 8.1). For example, up to half of those patients with chronic

urticaria have circulating anti-bodies directed against the high affinity

immuno-globulin E (IgE) receptor on mast cells whereas the reaction in others

in this group may be caused by immediate IgE-mediated hypersensitivity (see

Fig. 2.14), direct degranulation by a chemical or trauma, or even spontaneous

degranulation.

Classification

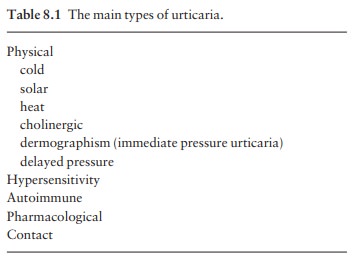

The

various types of urticaria are listed in Table 8.1. They can often be

identified by a careful history; laboratory tests are less useful. The duration

of the wheals is an important pointer. Contact and physical urticarias, with

the exception of delayed pressure urticaria, start shortly after the stimulus

and go within an hour. Individual wheals of other forms resolve within 24 h.

Physical urticarias

Cold urticaria

Patients

develop wheals in areas exposed to cold, e.g.

on

the face when cycling or freezing in a cold wind.

A useful test in the clinic is to reproduce the reac-tion by holding an ice cube, in a thin plastic bag to avoid wetting, against forearm skin. A few cases are associated with the presence of cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins or cryofibrinogens.

Solar urticaria

Wheals

occur within minutes of sun exposure. Some patients with solar urticaria have

erythropoietic protoporphyria; most have an IgE-mediated urticarial reaction to

sunlight.

Heat urticaria

In

this condition wheals arise in areas after contact with hot objects or

solutions.

Cholinergic urticaria

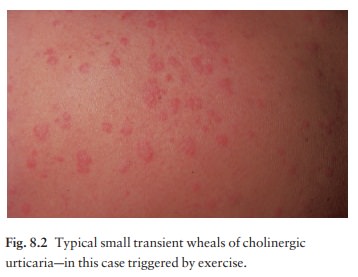

Anxiety,

heat, sexual excitement or strenuous exercise elicits this characteristic

response. The vessels over-react to acetylcholine liberated from sympathetic

nerves in the skin. Transient 2–5 mm follicular macules or papules (Fig. 8.2)

resemble a blush or viral exanthem. Some patients get blotchy patches on their

necks.

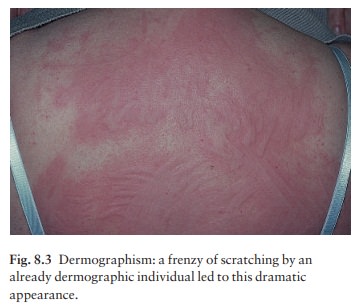

Dermographism (Fig.

8.3)

This

is the most common type of physical urticaria, the skin mast cells releasing

extra histamine after rub-bing or scratching. The linear wheals are therefore

an exaggerated triple response of Lewis. They can readily be reproduced by

rubbing the skin of the back lightly at different pressures, or by scratching

the back with a fingernail or blunt object.

Delayed pressure urticaria

Sustained pressure causes oedema of the underlying skin and subcutaneous tissue 3– 6 h later.

The swelling may

last up to 48 h and kinins or prostaglandins rather than histamine probably

mediate it. It occurs particularly on the feet after walking, on the hands

after clapping and on the buttocks after sitting. It can be disabling for

manual labourers.

Other types of urticaria

Hypersensitivity urticaria

This

common form of urticaria is caused by hyper-sensitivity, often an IgE-mediated

(type I) allergic reaction . Allergens may be encountered in ten different ways

(the 10 ‘I’s listed in Table 8.2).

Autoimmune urticaria

Some patients with chronic urticaria have an auto-immune disease with IgG antibodies to IgE or to FcIgE receptors on mast cells. Here the autoantibody acts as antigen to trigger mast cell degranulation.

Pharmacological urticaria

This

occurs when drugs cause mast cells to release histamine in a non-allergic

manner (e.g. aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and morphine).

Contact urticaria

This

may be IgE-mediated or caused by a pharmaco-logical effect. Wheals occur most

often around the mouth. Foods and food additives are the most com-mon culprits

but drugs, animal saliva, caterpillars and plants may cause the reaction.

Recently, latex allergy has become a significant public health concern.

Latex allergy

Possible

reactions to the natural rubber latex of the Hevea brasiliensis tree

include irritant dermatitis, con-tact allergic dermatitis and type I allergy . Reactions associated

with the latter include hypersensitivity urticaria (both by contact and by

inhalation), hay fever, asthma, anaphylaxis and, rarely, death.

Medical

latex gloves became universally popular after precautions were introduced to

protect against HIV and hepatitis B infections. The demand for the gloves

increased and this led to alterations in their manu-facture and to a flood of

high allergen gloves on the market. Cornstarch powder in these gloves bound to

the latex proteins so that the allergen became airborne when the gloves were

put on. Individuals at increased risk of latex allergy include health care

workers, those undergoing multiple surgical procedures (e.g. spina bifida

patients) and workers in mechanical, catering and electronic trades. Around 1–

6% of the general population is believed to be sensitized to latex.

Latex reactions should be treated on their own merits. Preven-tion of latex allergy is equally important. Non-latex (e.g. vinyl) gloves should be worn by those not han-dling infectious material (e.g. caterers) and, if latex gloves are chosen for those handling infectious material, then powder-free low allergen ones should be used.

Presentation

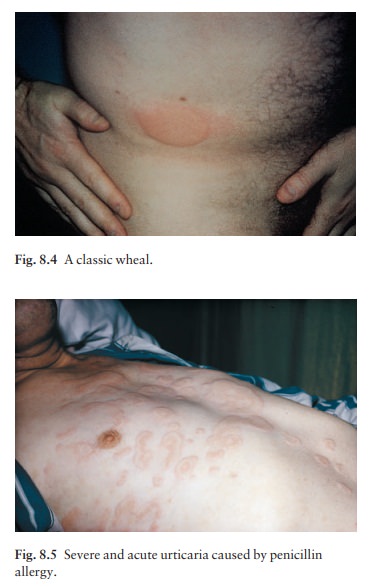

Most

types of urticaria share the sudden appear-ance of pink itchy wheals, which can

come up any-where on the skin surface (Figs 8.4 and 8.5). Each lasts for less

than a day, and most disappear within a few hours. Lesions may enlarge rapidly

and some resolve centrally to take up an annular shape. In an acute

anaphylactic reaction, wheals may cover most of the skin surface. In contrast,

in chronic urticaria only a few wheals may develop each day.

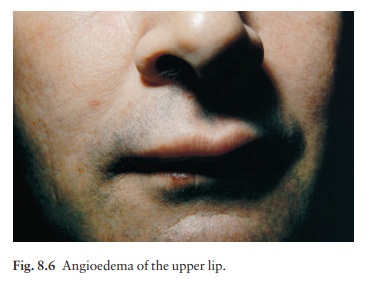

Angioedema

is a variant of urticaria that primarily affects the subcutaneous tissues, so

that the swelling is less demarcated and less red than an urticarial wheal.

Angioedema most commonly occurs at junctions between skin and mucous membranes

(e.g. peri-orbital, peri-oral and genital; Fig. 8.6). It may be associated with

swelling of the tongue and laryngeal mucosa. It sometimes accompanies chronic

urticaria and its causes may be the same.

Course

The

course of an urticarial reaction depends on its cause. If the urticaria is

allergic, it will continue until the allergen is removed, tolerated or

metabolized. Most such patients clear up within a day or two, even if the

allergen is not identified. Urticaria may recur if the allergen is met again.

At the other end of the scale, only half of patients attending hospital clinics

with chronic urticaria and angioedema will be clear 5 years later. Those with

urticarial lesions alone do better, half being clear after 6 months.

Complications

Urticaria

is normally uncomplicated, although its itch may be enough to interfere with

sleep or daily activit-ies and to lead to depression. In acute anaphylactic

reactions, oedema of the larynx may lead to asphyxi-ation, and oedema of the

tracheo-bronchial tree may lead to asthma.

Differential diagnosis

There

are two aspects to the differential diagnosis of urticaria. The first is to

tell urticaria from other eruptions that are not urticaria at all. The second

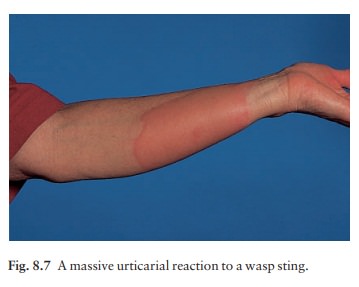

is to define the type of urticaria, according to Table 8.1. Insect bites or

stings (Fig. 8.7) and infestations com-monly elicit urticarial responses, but

these may have a central punctum and individual lesions may last longer than 24

h. Erythema multiforme can mimic an annular urticaria. A form of vasculitis

(urticarial vasculitis) may resemble urticaria, but indi-vidual lesions last

for longer than 24 h and may leave

Some bullous diseases, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous

pemphigoid and pemphigoid gestationis, begin as urticarial papules or plaques,

but later bullae make the diagnosis obvious. On the face, erysipelas can be

distinguished from angioedema by its sharp margin, redder colour and

accompanying pyrexia. Hereditary angioedema must be distinguished from the

angioedema accompanying urticaria as their treatments are completely different.

Hereditary angioedema

Recurrent

attacks of abdominal pain and vomiting, or massive oedema of soft tissues,

which may involve the larynx, characterize this autosomal dominant con-dition.

Urticaria does not accompany the tissue swel-lings. Tooth extraction, cheek

biting and other forms of trauma may precipitate an attack. A deficiency of an

inhibitor to C1 esterase allows complement con-sumption to go unchecked so that

vasoactive mediators are generated. To confirm the diagnosis, serum C1 esterase

inhibitor level and C4 level should both be checked as the level of C1 esterase

inhibitor is not always depressed (there is a type where the inhibitor is

present but does not work).

Investigations

The investigations will depend upon the presentation and type of urticaria. Many of the physical urticarias can be reproduced by appropriate physical tests. It is important to remember that antihistamines should be stopped for at least 3 days before these are undertaken.

Almost

invariably, more is learned from the history than from the laboratory. The

history should include details of the events surrounding the onset of the

erup-tion. A review of systems may uncover evidence of an underlying disease.

Careful attention should be paid to drugs, remembering that self-prescribed

ones can also cause urticaria. Over-the-counter medications (such as aspirin

and herbal remedies) and medications given by other routes (Table 8.2) can

produce wheals.

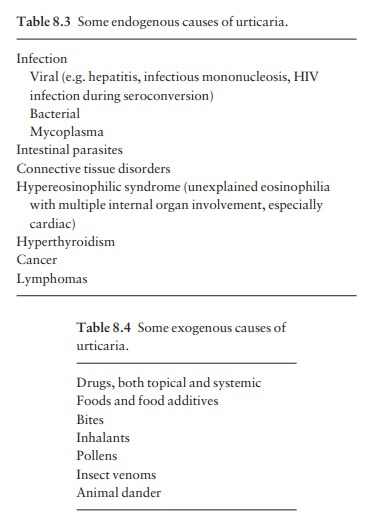

If

a patient has acute urticaria and its cause is not obvious, investigations are

often deferred until it has persisted for a few weeks; then a physical

examination (if not already carried out) and screening tests such as a complete

blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), routine biochemical screen,

chest X-ray and urine analysis are worthwhile. If the urticaria continues for

2–3 months, the patient should prob-ably be referred to a dermatologist for

further evalu-ation. In general, the focus of such investigations will be on

internal disorders associated with urticaria (Table 8.3) and on external

allergens (Table 8.4). Even after extensive evaluation and environmental

change, the cause cannot always be found.

In

some patients with acute or contact urticaria, allergy testing in the form of

radioallergosorbant tests (RAST) or prick tests , using only allergens

suggested by the history, can sometimes be of help. Many patients with chronic

urticaria are sure that their problems could be solved by intensive allergy

tests, and ask repeatedly for them, but this is seldom worthwhile.

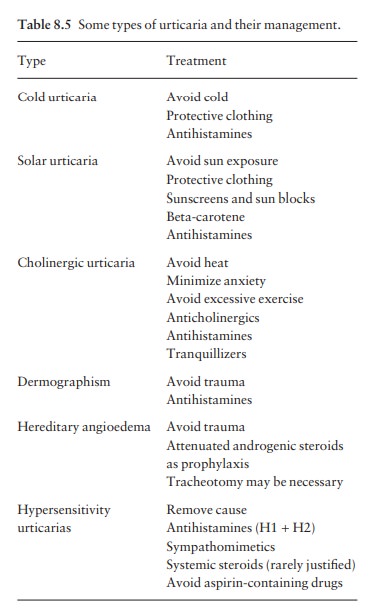

Treatment

The

ideal is to find a cause and then to eliminate it. In addition, aspirinain any

formashould be banned. The treatment for each type of urticaria is outlined in

Table 8.5. In general, antihistamines are the mainstays of symptomatic

treatment. Cetirizine 10 mg/day and loratadine 10 mg/day, both with half-lives

of around 12 h, are useful. If necessary, these can be supplemented

Alternatively they can

be combined with a longer acting antihistamine (such as chlorpheniramine

maleate 12 mg sustained-release tablets every 12 h) so that peaks and troughs

are blunted, and histamine activity is blocked throughout the night. If the

eruption is not controlled, the dose of hydroxyzine can often be increased and

still tolerated. H2-blocking antihistamines (e.g. cimetidine) may add a slight

benefit if used in conjunction with an H1 histamine antagonist.

Chlorpheniramine or diphen-hydramine are often used during pregnancy because of

their long record of safety, but cetirizine, loratidine and mizolastine should

be avoided. Sympathomimetic agents can help urticaria, although the effects of

adrena-line (epinephrine) are short lived. Pseudoephedrine (30 or 60 mg every 4

h) or terbutaline (2.5 mg every 8 h) can sometimes be useful adjuncts.

A

tapering course of systemic corticosteroids may be used, but only when the

cause is known and there are no contraindications, and certainly not as a

panacea to control chronic urticaria or urticaria of unknown cause. For the

treatment of anaphylaxis.

Related Topics