Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Reactive erythemas and vasculitis

Leucocytoclastic

Leucocytoclastic (small vessel) vasculitis (Syn: allergic or hypersensitivity vasculitis, anaphylactoid purpura)

Cause

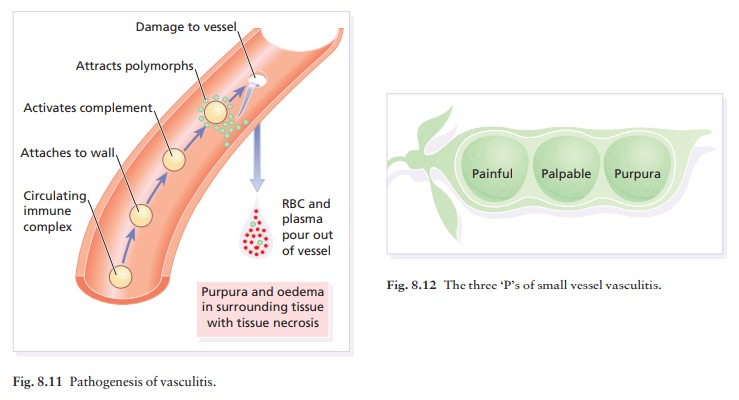

Immune

complexes may lodge in the walls of blood vessels, activate complement and

attract polymor-phonuclear leucocytes (Fig. 8.11). Enzymes released from these

can degrade the vessel wall. Antigens in these immune complexes include drugs,

auto-antigens, and infectious agents such as bacteria.

Presentation

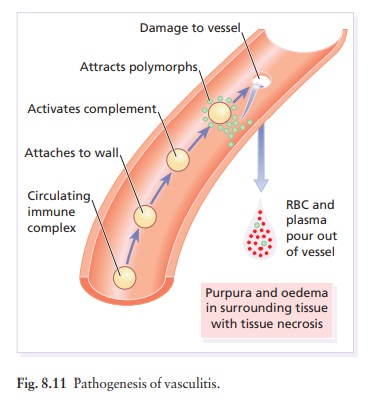

The most common presentation of vasculitis is painful palpable purpura (Fig. 8.12). Crops of lesions arise in dependent areas (the forearms and legs in ambulatory patients, or on the buttocks and flanks in bedridden ones; Fig. 8.13). Some have a small, livid or black centre, caused by necrosis of the tissue overlying the affected blood vessel.

Henoch–Schönlein

purpura is a small vessel vas-culitis associated with palpable purpura,

arthritis and abdominal pain, often preceded by an upper respirat-ory tract

infection. Children are most commonly, but not exclusively, affected.

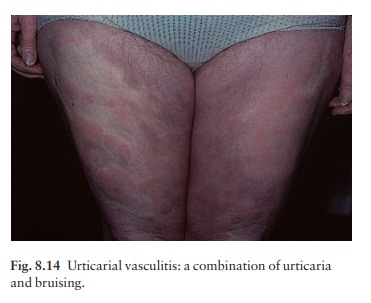

Urticarial vasculitis is a small vessel vasculitis char-acterized by urticaria-like lesions which last for longer than 24 h, leaving bruising and then pigmentation (haemosiderin) at the site of previous lesions (Fig. 8.14). There may be foci of purpura in the wheals and other skin signs include angioedema. General features include malaise and arthralgia.

Course

The

course of the vasculitis varies with its cause, its extent, the size of blood

vessel affected, and the involvement of other organs.

Complications

Vasculitis

may simply be cutaneous; alternatively, it may be systemic and then other

organs will be damaged, including the kidney, central nervous sys-tem,

gastrointestinal tract and lungs.

Differential diagnosis

Small

vessel vasculitis has to be separated from other causes of purpura such as abnormalities of the clotting system

and sepsis (with or without vasculitis). Vasculitic purpuras are raised

(palpable). Occasionally, the vasculitis may look like urticaria if its purpuric

element is not marked. Blanching such an urticarial papule with a glass slide

may reveal subtle purpura.

Investigations

Investigations

should be directed toward identifying the cause and detecting internal

involvement. Ques-tioning may indicate infections; myalgias, abdominal pain,

claudication, mental confusion and mononeuritis may indicate systemic

involvement. A physical examination, chest X-ray, ESR and biochemical tests

mon-itoring the function of various organs are indicated. However, the most

important test is urine analysis, checking for proteinuria and haematuria,

because vasculitis can affect the kidney subtly and so lead to renal

insufficiency.

Skin

biopsy will confirm the diagnosis of small vessel vasculitis. The finding of

circulating immune complexes, or a lowered level of total complement (CH50) or

C4, will implicate immune complexes as its cause. Tests for hepatitis virus,

cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies may also be needed.

Direct

immunofluorescence can be used to identify immune complexes in blood vessel

walls, but is seldom performed because of false-positive and false-negative

results, as inflammation may destroy the complexes in a true vasculitis and

induce non-specific deposition in other diseases. Henoch–Schönlein vasculitis

is con-firmed if IgA deposits are found in the blood vessels of a patient with

the clinical triad of palpable purpura, arthritis and abdominal pain.

Treatment

The

treatment of choice is to identify the cause and eliminate it. In addition,

antihistamines and bed rest sometimes help. Colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily or

dapsone 100 mg daily may be worth a trial, but require monitoring for

side-effects. Pati-ents whose vasculitis is damaging the kidneys or other

internal organs may require systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive

agents such as cyclophosphamide.

Related Topics