Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Critical Thinking,Ethical Decision Making, and the Nursing Process

Types of Ethical Problems in Nursing

TYPES

OF ETHICAL PROBLEMS IN NURSING

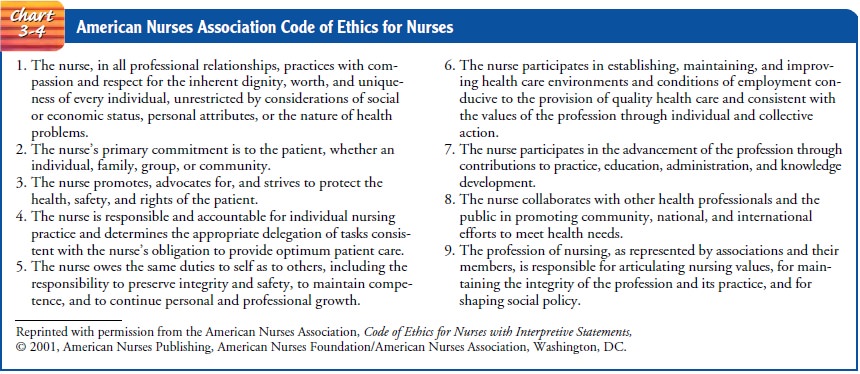

As a profession, nursing

is accountable to society. This account-ability is spelled out in the American

Hospital Association’s Patient Care Partnership (Chart 3-3), which reflects

social beliefs about health and health care. In addition to accepting this

document as one measure of accountability, nursing has further defined its

standards of accountability through a formal code of ethics that explicitly

states the profession’s values and goals. The code (Chart 3-4), established by

the American Nurses Association (ANA), consists of ethical standards, each with

its own interpre-tive statements (ANA, 2001). The interpretive statements

provide guidance to address and resolve ethical dilemmas by incorporating

universal moral principles (ANA’s Code of Ethics Project Task Force, 2000). The

code is an ideal framework for nurses to use in ethical decision making.

Ethical issues have

always affected the role of the professional nurse. The accepted definition of

professional nursing has inspired a new advocacy role for nurses. The ANA, in Nursing’s Social Pol-icy Statement (1995),

defines nursing as “the diagnosis and treat-ment of human responses to health

and illness.” This definition supports the claim that nurses must be actively

involved in the decision-making process regarding ethical concerns surrounding

health care and human responses. Efforts to enact this standard may cause

conflict in health care settings in which the traditional roles of the nurse

are delineated within a bureaucratic structure. If, however, nurses learn to present

ethical conflicts within a logi-cal, systematic framework, struggles over

jurisdictional boundaries may decrease. Health care settings in which nurses

are valued members of the team promote interdisciplinary communication and may

enhance patient care. To practice effectively in these set-tings, nurses must

be aware of ethical issues and assist patients in voicing their moral concerns.

The basic ethical

framework of the nursing profession is the phenomenon of human caring. Nursing

theories that incorporate the biopsychosocial–spiritual dimensions emphasize a

holistic viewpoint, with humanism or caring as the core. As the nursing

profession strives to delineate its own theory of ethics, caring is often cited

as the moral foundation. For nurses to embrace this professional ethos, it is

necessary to be aware not only of major ethical dilemmas but also of those

daily interactions with health care consumers that frequently give rise to

ethical challenges that are not as easily identified. Although technological

advances and diminished resources have been instrumental in raising numer-ous

ethical questions and controversies, including life-and-death issues, nurses

should not ignore the many routine situations that involve ethical

considerations. Some of the most common issues faced by nurses today include

confidentiality, use of restraints, trust, refusing care, genetics, and

end-of-life concerns.

Confidentiality

We all need to be aware

of the confidential nature of information obtained in daily practice. If information

is not pertinent to a case, the nurse should question whether it is prudent to

record it in the patient’s chart. In the practice setting, discussion of the

pa-tient with other members of the health care team is often neces-sary. These

discussions should, however, occur in a private area where it is unlikely that

the conversation will be overheard.

Another threat to

keeping information confidential is the widespread use of computers and the

easy access people have to them. This may increase the potential for misuse of

information, which may have negative social consequences (Zolot, 1999). For

example, laboratory results regarding testing for human immuno-deficiency virus

(HIV) infection or genetic screening may lead to loss of employment or insurance

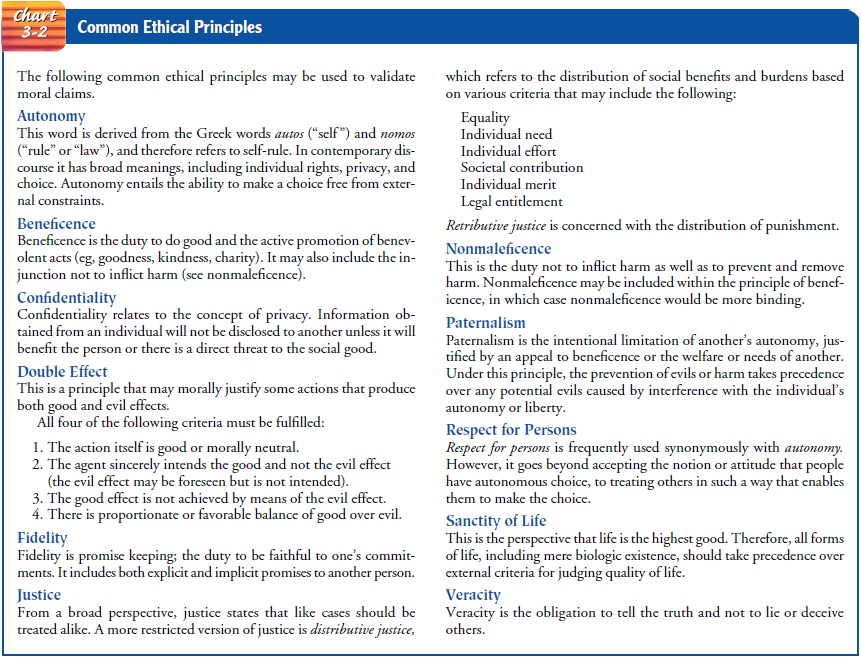

if the information is disclosed. Because of these possibilities of maleficence

(see Chart 3-2) to the patient, sensitivity to the principle of confidentiality

is essential.

Restraints

The use of restraints

(including physical and pharmacologic mea-sures) is another issue with ethical

overtones. It is important to weigh carefully the risks of limiting a person’s

autonomy and in-creasing the risk of injury by using restraints against the

risks of not using restraints. Before restraints are used, other strategies,

such as asking family members to sit with the patient, should be tried (Rogers

& Bocchino, 1999). The Joint Commission on Accredi-tation of Healthcare

Organizations (JCAHO) and the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) have

designated standards for use in care of patients with restraints; these

standards are available on the website listed later.

Trust Issues

Telling the truth (veracity) is one of the basic principles of our culture. Two ethical dilemmas in clinical practice that can di-rectly conflict with this principle are the use of placebos (non-active substances used to treat symptoms) and not revealing a di-agnosis to the patient. Both involve the issue of trust, which is an essential element in the nurse–patient relationship. Placebos may be used in experimental research, where the patient is involved in the decision-making process and is aware that placebos are being used in the treatment regimen. However, the use of a placebo as a substitute for an active drug to show that the patient does not have real symptoms is deceptive. This practice may severely un-dermine the nurse–patient relationship.

Informing patients of their diagnoses when the family and physician have chosen to withhold information is a common eth-ical situation in nursing practice. The nursing staff often use evasive comments with the patient as a means to maintain profes-sional relationships with other health practitioners.

This area is in-deed complex because it challenges the nurse’s integrity. Trust and connection with the patient play an important part in optimizing care (Day & Stannard, 1999). Strategies the nurse could consider in this situation include the following:

• Not lying to the patient

• Providing all information related to nursing procedures and diagnoses

• Communicating to the family and physician the patient’s requests for information

Families often are unaware of the patient’s repeated questions to the nurse. With a better understanding of the situation, fami-lies may change their perspective. Finally, although providing the information may be the morally appropriate behavior, the man-ner in which the patient is told is important. Nurses must be compassionate and caring while informing patients; disclosure of information merely for the sake of patient autonomy does not convey respect for others.

Refusing to Provide Care

Any nurse who feels compelled to refuse to provide care for a par-ticular type of patient faces an ethical dilemma. The reasons given for refusal range from a conflict of personal values to fear of per-sonal risk of injury. Such instances have increased since the ad-vent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) as a major health problem. In one survey, the number of nurses who stated they might refuse to care for a patient with AIDS declined over a 10-year period, from 75% to 20%. The number who might refuse to care for a patient with AIDS who was violent or uncooperative, however, rose from 72% to 82% (Ventura, 1999).

The ethical obligation to care for all patients is clearly identified in the first statement of the Code of Ethics for Nurses. To avoid facing these moral situations, a nurse can follow certain strategies. For example, when applying for a job, one should ask questions re-garding the patient population. If one is uncomfortable with a par-ticular situation, then not accepting the position would be an option. Denial of care, or providing substandard nursing care to some members of our society, is not acceptable nursing practice.

End-of-Life Issues

Dilemmas that center on death

and dying are prevalent in medical-surgical nursing practice and frequently

initiate moral discussion. The dilemmas are compounded by the fact that the

idea of curing is paramount in health care. With advanced technology, it may be

difficult to accept the fact that nothing more can be done, or that technology

may prolong life but at the expense of comfort and quality of life. Focusing on

the caring as well as the curing role may assist nurses in dealing with these

difficult moral situations.

PAIN CONTROL

The use of opioids to alleviate a patient’s pain may present a dilemma

for nurses. Patients with excruciating pain may require large doses of

analgesics. Fear of respiratory depression or un-warranted fear of addiction

should not prevent nurses from at-tempting to alleviate pain for the dying

patient or for a patient experiencing an acute pain episode. In the case of the

terminally ill patient, for example, the actions may be justified by the

princi-ple of double effect (see Chart 3-2). The intent or goal of nursing

interventions is to alleviate pain and suffering while promoting comfort. The

risk of respiratory depression is not the intent of the actions and should not

be used as an excuse for withholding anal-gesia. However, the patient’s

respiratory status should be carefully monitored and any signs of respiratory

depression reported to the physician. The administration of analgesia should be

governed by the patient’s needs.

DO-NOT-RESUSCITATE ORDERS

The “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order is a controversial issue. When a

patient is competent to make decisions, his or her choice for a DNR order

should be honored, according to the principles of autonomy or respect for the

individual (Trammelleo, 2000). However, a DNR order is at times interpreted to

mean that the patient requires less nursing care, when actually these patients

may have significant medical and nursing needs, all of which de-mand attention.

Ethically, all patients deserve and should receive appropriate nursing

interventions, regardless of their resuscita-tion status.

LIFE SUPPORT

In contrast to the

previous situations are those in which a DNR decision has not been made by or

for a dying patient. The nurse may be put in the uncomfortable position of

initiating life-support measures when, because of the patient’s physical

condition, they appear futile. This frequently occurs when the patient is not

competent to make the decision and the family (or surrogate de-cision maker)

refuses to consider a DNR order as an option. The nurse may be told to perform

a “slow code” (ie, not to rush to re-suscitate the patient) or may be given a

verbal order not to resus-citate the patient; both are unacceptable medical

orders. The best recourse for nurses in these situations is to be aware of

hospital policy related to the Patient Self-Determination Act (discussed later)

and execution of advance directives. The nurse should communicate with the

physician. Discussing the matter with the physician may lead to further

communication with the family and to a reconsideration of their decision,

especially if they are afraid to let a loved one die with no further efforts to

resuscitate (Trammelleo, 2000). Finally, when working with colleagues who are

confronting such difficult situations, it helps to talk and lis-ten to their

concerns as a way of providing support.

FOOD AND FLUID

In addition to

requesting that no heroic measures be taken to pro-long life, a dying patient

may request that no more food or fluid be administered. Many individuals think

that food and hydration are basic human needs, not “invasive measures,” and

therefore should always be maintained. However, some consider food and

hydration as means of prolonging suffering. In evaluating this issue, nurses

must take into consideration the potential harm as well as the benefit to the

patient of either administering or with-drawing sustenance. Research has not

supported the belief that withholding fluids results in a painful death due to

thirst (Smith, 1997; Zerwekh, 1997).

Evaluation of harm

requires a careful review of the reasons the person has requested the

withdrawal of food and hydration. Although the principle of autonomy has

considerable merit and is supported by the Code of Ethics for Nurses, there may

be sit-uations when the request for withdrawal of food and hydration cannot be

upheld. For patients with decreased decision-making capacity, the issues are

more complex. Some of these cases have reached courts of law, and different

states have different case law precedents forbidding withdrawal of sustenance.

Although an ad-vance directive may provide some answers, at present there are

no firm guidelines to assist nurses in this area.

Related Topics