Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Critical Thinking,Ethical Decision Making, and the Nursing Process

Domain of Nursing Ethics

Domain of Nursing Ethics

The ethical dilemmas a

nurse may encounter in the medical-surgical arena are numerous and diverse. An

awareness of under-lying philosophical concepts will help the nurse to reason

through these dilemmas. Basic concepts related to moral philosophy, such as

ethics terminology, theories, and approaches. Understanding the role of the

professional nurse in ethical decision making will assist nurses in

articulating their ethical posi-tions and in developing the skills needed to

make ethical decisions.

ETHICS VERSUS MORALITY

The terms ethics and morality are used to describe beliefs about right and wrong and to

suggest appropriate guidelines for action. In essence, ethics is the formal,

systematic study of moral beliefs, whereas morality is the adherence to

informal personal values. Because the distinction between the two is slight,

they are often used interchangeably.

ETHICS THEORIES

One classic theory in

ethics is teleologic theory or consequential-ism, which focuses on the ends or

consequences of actions. The most well-known form of this theory,

utilitarianism, is based on the concept of “the greatest good for the greatest

number.” The choice of action is clear under this theory, because the action

that maximizes good over bad is the correct one. The theory poses dif-ficulty

when one must judge intrinsic values and determine whose good is the greatest.

Additionally, the question must be asked whether good consequences can justify

any amoral actions that might be used to achieve them.

Another theory in ethics

is the deontologic or formalist theory, which argues that moral standards or

principles exist independently of the ends or consequences. In a given

situation, one or more moral principles may apply. The nurse has a duty to act

based on the one relevant principle, or the most relevant of several moral

principles. Problems arise with this theory when personal and cultural biases

influence the choice of the most primary moral principle.

APPROACHES TO ETHICS

Two approaches to ethics

are metaethics and applied ethics. An example of metaethics (understanding the

concepts and linguis-tic terminology used in ethics) in the health care

environment would be analysis of the concept of informed consent. Nurses are

aware that patients must give consent before surgery, but some-times a question

arises as to whether the patient is truly informed. Delving more deeply into

the concept of informed consent would be a metaethical inquiry.

Applied ethics is the

term used when questions are asked of a specific discipline to identify ethical

problems within that disci-pline’s practice. Various disciplines use the

frameworks of general ethical theories and moral principles and apply them to

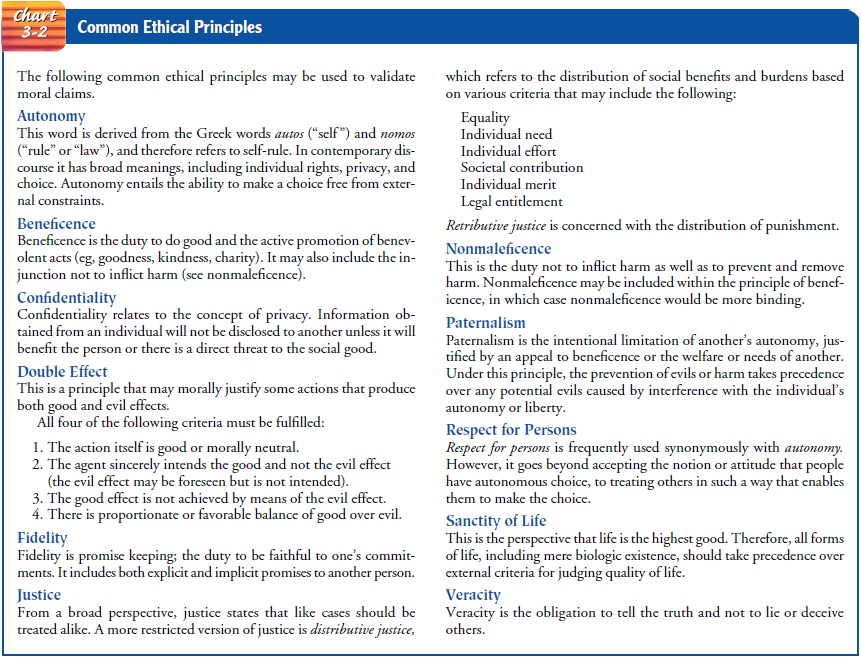

specific problems within their domain. Common ethical principles that apply in

nursing include autonomy, beneficence, confidentiality, double effect,

fidelity, justice, nonmaleficence, paternalism, re-spect for people, sanctity

of life, and veracity. Brief definitions of these important principles can be

found in Chart 3-2.

Nursing ethics may be

considered a form of applied ethics be-cause it addresses moral situations that

are specific to the nursing profession and patient care. Some ethical problems

that affect nursing may also apply to the broader area of bioethics and health

care ethics. However, the nursing profession is a “caring” rather than a

predominantly “curing” profession; therefore, it is imperative that one not

equate nursing ethics solely with medical ethics, because the medical

profession has a “cure” focus. Nursing has its own professional code of ethics.

MORAL SITUATIONS

Many situations exist in

which ethical analysis is needed. Some are moral

dilemmas, situations in which a clear conflict exists betweentwo or more

moral principles or competing moral claims, and the nurse must choose the

lesser of two evils. Other situations repre-sent moral problems, in which there may be competing moral claims or

principles but one claim or principle is clearly dominant. Some situations

result in moral uncertainty, when one

cannot accurately define what the moral situation is, or what moral principles

apply, but has a strong feeling that something is not right. Still other

sit-uations may result in moral distress,

in which the nurse is aware of the correct course of action but institutional

constraints stand in the way of pursuing the correct action (Jameton, 1984).

For example, a patient

tells a nurse that if he is dying he wants everything possible done. The surgeon

and family have made the decision not to tell the patient he is terminally ill

and not to re-suscitate him if he stops breathing. From an ethical perspective,

patients should be told the truth about their diagnoses and should have the

opportunity to make decisions about treatments. Ideally, this information

should come from the physician, with the nurse present to assist the patient in

understanding the terminology and to provide further support, if necessary. A

moral problem exists because of the competing moral claims of the family and

physi-cian, who wish to spare the patient distress, and the nurse, who wishes

to be truthful with the patient as the patient has requested. If the patient’s

competency were questionable, a moral dilemma would exist because no dominant

principle would be evident. The nurse could experience moral distress if the

hospital threatens dis-ciplinary action or job termination if the information

is disclosed without the agreement of the physician or the family, or both.

It is essential that

nurses freely engage in dialogue concerning moral situations, even though such

dialogue is difficult for every-one involved. Improved interdisciplinary

communication is sup-ported when all members of the health care team can voice

their concerns and come to an understanding of the moral situation. The use of

an ethics consultant or consultation team could be helpful to assist the health

care team, patient, and family to iden-tify the moral dilemma and possible

approaches to the dilemma. The nurse should be familiar with agency policy

supporting pa-tient self-determination and resolution of ethical issues. The

nurse should be an advocate for patient rights in each situation (Trammelleo,

2000).

TYPES OF ETHICAL PROBLEMS IN NURSING

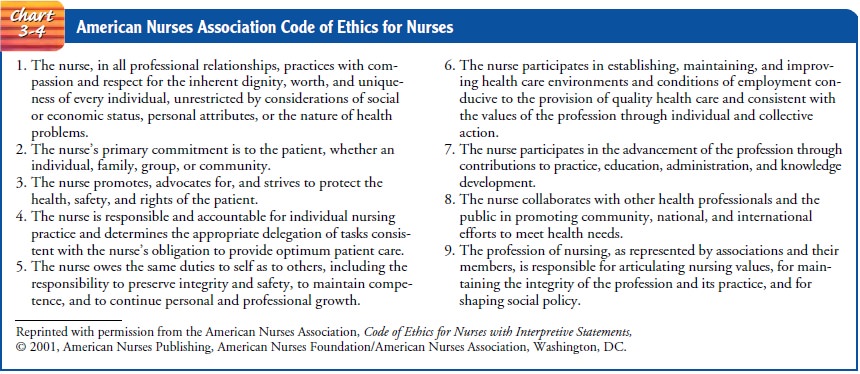

As a profession, nursing

is accountable to society. This account-ability is spelled out in the American

Hospital Association’s Patient Care Partnership (Chart 3-3), which reflects

social beliefs about health and health care. In addition to accepting this

document as one measure of accountability, nursing has further defined its

standards of accountability through a formal code of ethics that explicitly

states the profession’s values and goals. The code (Chart 3-4), established by

the American Nurses Association (ANA), consists of ethical standards, each with

its own interpre-tive statements (ANA, 2001). The interpretive statements

provide guidance to address and resolve ethical dilemmas by incorporating

universal moral principles (ANA’s Code of Ethics Project Task Force, 2000). The

code is an ideal framework for nurses to use in ethical decision making.

Ethical issues have

always affected the role of the professional nurse. The accepted definition of

professional nursing has inspired a new advocacy role for nurses. The ANA, in Nursing’s Social Pol-icy Statement (1995),

defines nursing as “the diagnosis and treat-ment of human responses to health

and illness.” This definition supports the claim that nurses must be actively

involved in the decision-making process regarding ethical concerns surrounding

health care and human responses. Efforts to enact this standard may cause

conflict in health care settings in which the traditional roles of the nurse

are delineated within a bureaucratic structure. If, however, nurses learn to present

ethical conflicts within a logi-cal, systematic framework, struggles over

jurisdictional boundaries may decrease. Health care settings in which nurses

are valued members of the team promote interdisciplinary communication and may

enhance patient care. To practice effectively in these set-tings, nurses must

be aware of ethical issues and assist patients in voicing their moral concerns.

The basic ethical

framework of the nursing profession is the phenomenon of human caring. Nursing

theories that incorporate the biopsychosocial–spiritual dimensions emphasize a

holistic viewpoint, with humanism or caring as the core. As the nursing

profession strives to delineate its own theory of ethics, caring is often cited

as the moral foundation. For nurses to embrace this professional ethos, it is

necessary to be aware not only of major ethical dilemmas but also of those

daily interactions with health care consumers that frequently give rise to

ethical challenges that are not as easily identified. Although technological

advances and diminished resources have been instrumental in raising numer-ous

ethical questions and controversies, including life-and-death issues, nurses

should not ignore the many routine situations that involve ethical

considerations. Some of the most common issues faced by nurses today include

confidentiality, use of restraints, trust, refusing care, genetics, and

end-of-life concerns.

Related Topics