Chapter: Essential Clinical Immunology: Autoimmunity

Type IIA Autoimmune Reaction: Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia - Mechanisms of Autoimmune Tissue Injury and Examples

Type IIA Autoimmune Reaction: Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

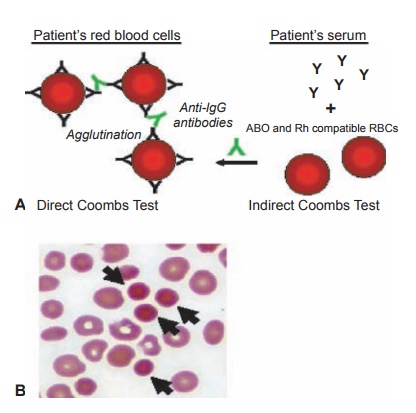

AIHA is an example of type IIA autoimmunity. In this disorder, a self-antigen on the surface of erythrocytes elicits an autoantibody response, resulting in the binding of autoantibody to the erythro-cyte surface followed by destruction of the antibody-coated erythrocytes by the reticuloendothelial system of the spleen and liver. The mechanism of hemolysis depends on the type of autoantibodies. Autoimmune hemolysis is classified into two groups on the basis of thermal reactiv-ity of the autoantibodies. Warm autoanti-bodies react optimally at temperatures of 35°C–40°C, whereas cold agglutinins and other cold-reactive autoantibodies react maximally at 4°C. Warm autoantibod-ies are typically polyclonal IgG but may also be IgM or IgA. Most are IgG1 sub-class antibodies reactive with Rh antigens. These antibodies are detected by the direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test (Figure 6.1A). Erythrophagocytosis mediated by Fc receptors on Kupffer cells in the liver and macrophages in the splenic marginal zone is generally the major mechanism of eryth-rocyte destruction in patients with warm autoantibodies.

In contrast, AIHA induced by cold agglutinins is complement mediated. These autoantibodies are of the IgM class and cannot interact with Fc receptors because there are no Fc receptors capable of binding the µ heavy chain. Idiopathic cold agglutinin disease generally is asso-ciated with an IgM paraprotein against the “I” antigen, an erythrocyte surface protein. Unlike IgG, which must be cross-linked, pentavalent IgM fixes complement efficiently without cross-linking. After binding to the erythrocyte’s surface at low temperature, IgM cold agglutinins acti-vate C1, C4, C2, and C3b. With rewarm-ing, the antibody can dissociate, but C3b remains fixed irreversibly, which can lead to recruitment of the terminal complement components (C5–C9, membrane attack complex) and intravascular hemolysis or C3b receptor-mediated phagocytosis by reticuloendothelial cells.

Figure 6.1 Autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

A, Diagram showing the difference between the direct and indirect Coombs test. B, Peripheral blood smear illustrating microspherocytes (arrows).

Case 1. Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia,

a Type II Autoimmune Reaction

A twenty-eight-year-old woman with a four-year history of SLE pre-sented for a scheduled follow-up in clinic. Because she avoids the sun and started taking hydroxychloroquine four years ago, her rash and arthritis had improved, but over the past six months, she had become progressively more fatigued and began to notice dark urine. Review of medications, alcohol intake, recreational drug use, and sick contacts was unrevealing. On physical exam, she was mildly tachycardic at 105, with a two out of six systolic ejec-tion murmur at the left sternal border, dullness to percussion over Traubes’ space (the normally resonant gastric bubble), and a palpable spleen tip.

Her hemoglobin was 9.5 g/dl (nor-mal 12–16 g/dl), mean cell volume (MCV, a measure of erythrocyte size) was normal at 88 cu µm, and platelets were 75,000/µl (normal 140–400,000/ µl). Urinalysis revealed no blood but was remarkable for urobilinogen of 8 mg/dl (normal <2 mg/dl). Hepatic panel was notable for a total bilirubin of 2 mg/dl (normal <1.5 mg/dl) with indi-rect bilirubin of 1.5 mg/dl (normal <0.8 mg/dl) and directbilirubin 0.5 mg/dl (normal <0.7 mg/dl). Lactate dehy-drogenase was elevated at 350 IU/L (normal <250 IU/L), and corrected retic-ulocyte count (immature erythrocytes) was 3 percent (normal <1 percent).

Direct Coombs test was positive (Figure 6.1A). Haptoglobin (a scaven-ger of free hemoglobin) was reduced to <5 mmol/L (normal 10–30 mmol/ L). Parvovirus B19, thyroid-stimulat-ing hormone (TSH), vitamin B12 level, folate level, iron profile, and ferritin were unremarkable. A review of her blood smear showed numerous sphe-rocytes (spherical erythrocytes instead of the usual biconcave disc shape, the result of damage to the red cell mem-brane as it passes through the spleen; Figure 6.1B) and confirmed thrombocy-topenia (low numbers of platelets). An ultrasound of her abdomen revealed a normal liver but an enlarged spleen.

On the basis of these clinical find-ings, the diagnoses of AIHA and thrombocytopenia were made. She was treated with prednisone (a corticoste-roid) at a dose of 60 mg/day. Initially, her platelet count improved to 120,000. However, after three months of treat-ment, her anemia did not improve. She gained twenty pounds and noted easy bruising, fatigue, and difficulty sleeping as well as “feeling on edge all the time.” Since she had not improved and was experiencing side effects of prednisone, she was given a pneumococcal pneu-monia vaccination before surgery to remove her spleen. After splenectomy,

her anemia, thrombocytopenia, and some of her fatigue resolved. After tapering the prednisone dose, she “felt normal.” Two years later, her symptoms recurred and laboratory tests confirmed evidence of active hemolytic anemia. A liver-spleen scan indicated the presence of an accessory spleen (present in 10–30 percent of normal population), which was removed. She is currently symp-tom free.

COMMENT

AIHA in patients with SLE is usu-ally due to the presence of warm-reac-tive autoantibodies against the Rh antigen. As the autoantibody-coated erythrocytes pass through the spleen, phagocytes bearing Fc receptors remove some of the immunoglobulin on the cell surface along with some of the cell membrane, which subsequently reseals, causing the erythrocyte to take the form of a spherocyte. Eventually, the erythrocyte is unable to be repaired and is removed from the circulation. If this occurs faster than new erythrocytes can be produced (normal life span of an erythrocyte is about 120 days) then anemia develops. The elevated indirect bilirubin (a measure of bilirubin before the liver has a chance to process it) is a result of the increased breakdown of hemoglobin.

AIHA can occur in a variety of circumstances, including neoplas-tic diseases (most often lymphomas), connective tissue diseases (such as SLE), and infections (viral, bacterial, or mycoplasma). Or it may be drug induced (classically penicillin). The initial treatment is to diagnose and treat the underlying cause or remove offending agents. If this is not possible, corticosteroids such as prednisone are often used. If patients do not respond, then consideration is given to the use of cytotoxic drugs (e.g., azathioprine or vincristine) or splenectomy.

Related Topics