Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Treatment of Violent Behavior

Treatment of Violent Behavior: Long-term Treatment

Long-term

Treatment

The

treatment goal is to decrease the frequency and intensity of aggressive

behavior. Specialized units such as secure or psychiat-ric intensive care units

(Musisi et al., 1989; Goldney et al., 1985; Warneke, 1986; Citrome et al., 1995) provide a structured

envi-ronment that optimizes staff and patient safety. In general these

specialized units are staffed with persons trained in interacting with volatile

and difficult to manage patients (Maier et

al., 1987). When available, these units can be a valuable resource for

educa-tion, training, consultation and referral.

Although

pharmacotherapy remains a mainstay of treat-ment for the persistently

aggressive patient, behavioral plans need to be used in tandem. Providing

structure, including the use of behavioral contracts, can be useful. Preventive

aggression devices (PADS) are a form of ambulatory restraints, which can be

used as an alternative to seclusion (Van Rybroek et al., 1987). The technique was first developed for a specialized

inpatient unit

with

repetitively aggressive patients. Patients in these wrist-to-belt and/or

ankle–ankle restraints can remain with their peers on the ward, eat their meals

and interact, yet are prevented from striking out and injuring others. In combination

with a compre-hensive behavior modification program, these patients can be

weaned off the use of the ambulatory restraints.

Although

pharmacotherapy for the longer-term man-agement of aggressive behavior is

somewhat dependent on the patient’s underlying diagnosis, clinical management

is often complicated and can entail the use of several coprescribed

medi-cations. At the core of impulsive aggressive behavior may be a

dysregulation of the serotonergic neurotransmitter system and this may explain

the possible ameliorative effects of atypical anti-psychotics and the selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In addition, beta-blockers and

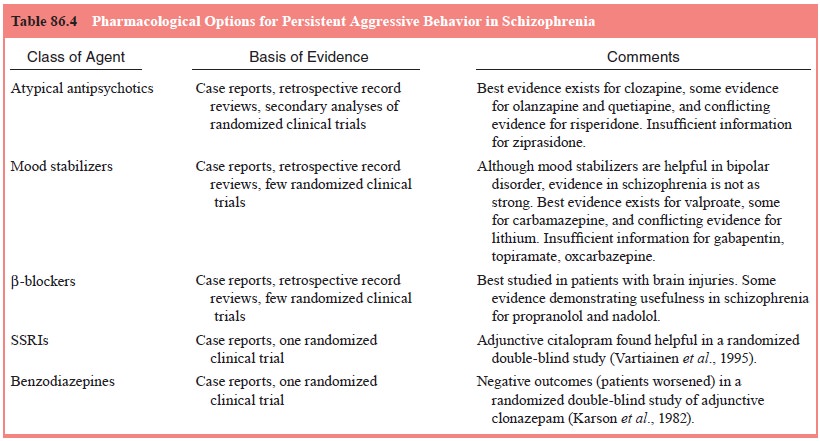

moodstabilizers have been used with some success. Table 86.4 outlines the

medication strategies useful in patients with aggressive behavior and

schizophrenia. Nonadherence to a treatment regimen may require the use of

out-patient commitment, now available in many jurisdictions.

Atypical Antipsychotics

The availability of atypical antipsychotics has led to the observa-tion that these agents may act differently from the older antipsy-chotics in that they may specifically target aggressive behavior. Several retrospective studies have demonstrated a decrease in the number of violent episodes and/or a decrease in the use of se-clusion or restraint among inpatients after they began clozapine treatment (Wilson and Claussen, 1995; Ratey et al., 1993; Chiles et al., 1994; Mallya et al., 1992; Spivak et al., 1997; Maier, 1992; Ebrahim et al., 1994). At this time, the weight of the evidence favors clozapine as specific antiaggressive treatment for schizo-phrenia patients (Glazer and Dickson, 1998), with demonstrated superiority to haloperidol and risperidone (Citrome et al., 2001). More research is needed to compare the other atypical antipsy-chotics with clozapine for this indication. Ideally, such studies need to be done double-blind with subjects specially selected because of their aggressive behavior. This is operationally quite diffi cult because of a number of logistical factors, including the relative rarity of aggressive events and consequent need for a large sample size and lengthy baseline and trial periods, as well as selection/consent bias (Volavka and Citrome, 1999).

Mood Stabilizers

There is

an expectation that adjunctive mood stabilizers can reduce aggressive and

impulsive behavior (Citrome, 1995). This is understandable when the primary

diagnosis is bipolar or schizoaffective disorder where the mood stabilizer is

treating the core symptoms of the disorder, but these agents, notably

valproate, lithium and carbamazepine, are also used, though less frequently, in

patients with schizophrenia.

Beta-blockers

Beta-adrenergic

blockers, in particular propranolol, have been used in the treatment of

aggressive behavior in brain injured patients (Yudofsky et al., 1981, 1984).

Propranolol has also been used as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia,

and a reduction in symptoms, including aggression, was found (Sheppard, 1979).

Nadolol may also be helpful (Ratey et al., 1992; Alpert et al., 1990; Allan et

al., 1996). Beta-blockers may exert some of

their effects by decreasing akathisia, which in turn may decrease agitation.

Benzodiazepines

Clonazepam,

a high potency benzodiazepine, had been reported useful in patients with

bipolar disorder. This result is in contrast

to a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive clonazepam in

13 schizophrenic patients receiving antipsychotics (Karson et al., 1982). In that study no

additional therapeutic benefit was observed and, in fact, four patients

demonstrated violent behavior during the course of clonazepam treatment.

Using

lorazepam for long-term management (in contrast to acute use as a “prn”) can be

problematic because of physiological tolerance. Missing scheduled doses of

lorazepam may result in withdrawal symptoms that can lead to agitation or

excitement, as well as irritability and a greater risk for aggressive behavior.

Antidepressants

The

current interest in certain antidepressants’ role in aggression is based on the

crucial role of serotonergic regulation of impulsive aggression against self

and others. A number of reports have emerged that posit a role for fluoxetine

(Goldman and Janecek, 1990), citalopram (Vartiainen et al., 1995) and fluvoxamine (Silver and Kushnir, 1998) in the

treatment of persistent aggressive behavior.

Adjunctive Electroconvulsive Therapy

Although

not often considered as a first-line treatment, adjunctive electroconvulsive

therapy (ECT) may be helpful in patients who have inadequately-responsive

psychotic symptoms (Fink and Sackeim, 1996). An open trial of ECT in

combination with risperidone in male patients with schizophrenia and aggression

resulted in a reduction in aggressive behavior for nine of the 10 patients

(Hirose et al., 2001). The

combination of ECT and clozapine may also be helpful. A review of 36 reported

cases treated with this combination, all of whom with a history of

treatment-resistance, revealed that approximately two-thirds benefited from

this treatment (Kupchik et al.,

2000).

Related Topics