Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Treatment of Violent Behavior

Pathophysiology of Aggressive Behavior

Pathophysiology

of Aggressive Behavior

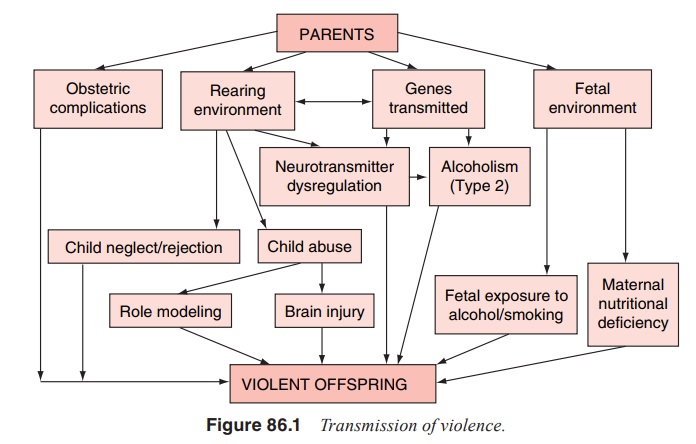

Several

principal pathways leading to a predisposition to aggres-sive behavior are

schematically displayed in Figure 86.1. The par-ents may contribute to the

offspring’s predisposition via transmit-ted genes, fetal environment, obstetric

complications and rearing environment. Several polymorphisms of genes that

control the activity of various neurotransmitters (particularly serotonin and

catecholamines) are apparently associated with persistent aggressive behavior.

Maternal use of alcohol, smoking and malnu-trition during pregnancy were all

reported to explain statistically significant (but clinically modest)

proportions of the variance of aggressive behavior in adult offspring.

Obstetric complica-tions, particularly in interaction with other factors such

as early maternal rejection, may lead to elevated rates of violent crime in the

offspring. Rearing environment not just limited to overt child abuse is one of

the most important factors in the development of predisposition to violence.

Detailed explanation of Figure 86.1, as well as the bibliography supporting it,

are presented elsewhere (Volavka, 2002).

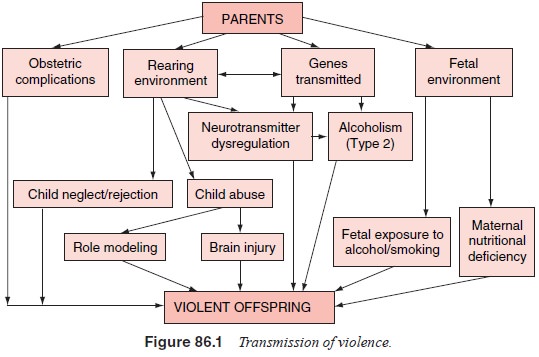

Mechanisms

displayed in Figure 86.2 may operate in per-sons with or without a diagnosable

mental disorder. We will now focus on aggressive behavior in persons with

mental disorders.

Substance Use Disorders

Acute

effects of alcohol and illicit drugs are involved, perhaps causally, in a large

proportion of aggressive incidents. For ex-ample, 51.6% of women injured during

a physical assault by a male partner reported that the assaulter had been

drinking just before the incident (Kyriacou et

al., 1999). Positive urine tests for illicit drugs were obtained in a

majority of arrested males in the USA. Epidemiological stud-ies indicate that

substance use disorders elevate substantially the prevalence of overt physical

aggression (Swanson, 1994).

Psychoses

Most

persons diagnosed with a psychosis are not violent. Never-theless, psychoses

are associated with an elevated risk for aggres-sion. It is clear that

comorbidity of psychosis and substance use disorder contributes to this risk

very substantially. Furthermore, persons with psychoses are more likely to have

substance use dis-orders than other people (Regier et al., 1990). Combination of sub-stance abuse and nonadherence to

treatment is the typical prelude to the development of aggressive behavior in

persons with severe mental illness living in the community (Swartz et al., 1998).

As every

hospital psychiatrist knows, there are many psy-chotic inpatients who are

aggressive without access to alcohol and drugs, and in spite of supervised

antipsychotic treatment. Thus, factors other than substance use and

nonadherence to treat-ment must be involved in the pathophysiology of

aggression in these patients.

From the

standpoint of practical management of aggres-sive patients with major mental

disorders, it seems that it could be fruitful to study in detail individual

assaults in order to assess underlying pathophysiology. This is a promising

avenue of re-search since it is generally agreed that aggressive behavior has

multiple causes that differ among patients, and perhaps among different

incidents in individual patients. Our experience, based on interviews of

assailants, victims and witnesses, as well as on observations of videotapes,

suggests that most assaults among psychiatric inpatients diagnosed with

psychoses are not driven by psychotic symptoms. It appears that many of these

assaults are attributable to comorbid personality disorders.

Personality Disorders

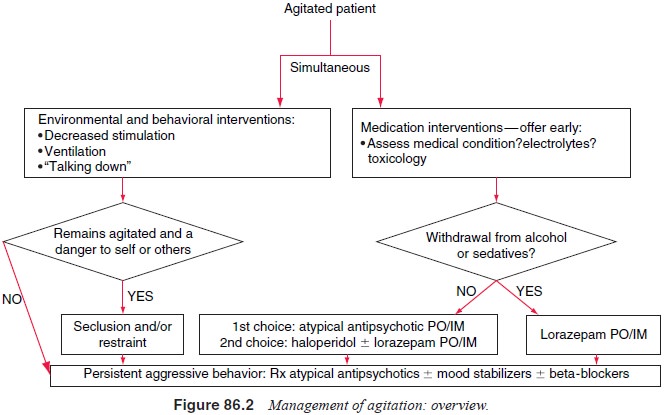

Antisocial

personality disorder (APD) is partly defined by aggres-sive behavior and

therefore it is not surprising that many violent psychotic patients meet its

diagnostic criteria. This circularity of definition makes the use of this

diagnosis somewhat unhelpful. The concept of “psychopathy”, introduced to

modern psychiatry by Cleckley (1976), is less circular since it relies

primarily on personality and psychological processes rather than on criminal or

aggressive behavior. Psychopathy is assessed by a valid and reliable checklist

constructed by Hare and his coworkers (Hart et

al., 1992). Table 86.1 shows the screening version of the check-list

intended for use in persons with serious mental illness (Hare, 1996; Hart et al., 1995). The first six items in Factor-1

measure the severity of interpersonal and affective symptoms of psychop-

athy. The

next six items in Factor-2 reflect the social deviance symptoms. Psychopathy is

a narrower concept than APD. Most psychopaths meet the criteria for APD, but

subjects diagnosed as APD do not necessarily meet the criteria for psychopathy.

Psy-chopathy predicts violent behavior in nonpsychotic individuals (Hare and

Hart, 1993), as well as in persons with major mental disorders (Hart et al., 1994). The rates of comorbidity

of psy-chopathy and schizophrenia are elevated among violent patients (Nolan et al., 1999).

Differentiating

aggressive behavior based on psychopa-thy from that based on psychotic symptoms

has consequences for treatment. It is unlikely that psychopathy will respond to

antipsychotics.

Related Topics