Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Combined Therapies: Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

Combined Therapies: Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

Combined Therapies: Psychotherapy

and Pharmacotherapy

The

rationale for combining treatment modalities is based on the idea that the

strengths of each modality are promoted while the weaknesses are minimized,

producing results that are better than with either modality alone (Hollon and

Fawcett, 1995). Although intuitively this rings true, psychiatrists have a duty

to incorporate evidence-based approaches into their clinical practice. While

most evidence-based mental health research in the literature is based on

efficacy studies, there has been a recent move towards conducting effectiveness

studies that are hoped to be of increased relevance to general outpatient

clinical practice (Nathan et al.,

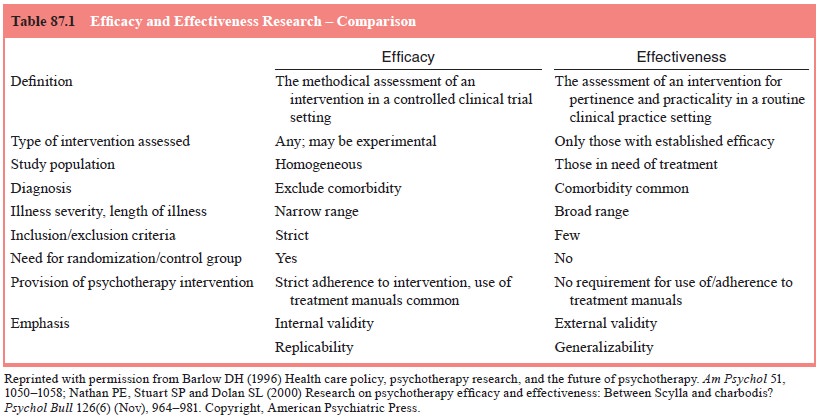

2000). Table 87.1 highlights the differences between efficacy and effectiveness

research (Barlow, 1996; Nathan et al.,

2000). Re-cent literature examining the efficacies of combined treatment (not

necessarily integrated treatment by a psychiatrist) vary by disorder, timing of

treatments and whether administered during the acute or maintenance phase.

Recent literature has also exam-ined the sequential application of combined

treatment (Fava et al., 2001; Frank et al., 2000). Effectiveness studies are

far fewer, as mentioned, and do not always demonstrate superiority of com-bined

approaches over either medication or therapy alone.

Hollon

and Fawcett (1995) have outlined four ways in which combined treatment may

prove advantageous over either treatment alone: increase the magnitude,

probability, or breadth of clinical response, and increase the acceptability to

the patient of either modality. In general, they feel that there is literature

to support the statement that combined treatment enhances the breadth of

clinical response. It is within this context that clini-cal practice guidelines

published by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research support the use of

combined treatment in depressive disorders (Depression Guideline Panel, 1993).

Various

authors discuss the potential benefits of employ-ing pharmacotherapy within a

psychotherapeutic context (Kler-man, 1991; Kay, 2001). Pharmacotherapy has been

noted to have a quicker onset of action on acute symptoms than most

psycho-therapies, perhaps with the exclusion of cognitive therapy (Hol-lon and

Fawcett, 2001). It is felt that this rapid dampening of symptoms may enhance

the patient’s ability to more productively participate in therapy by a variety

of mechanisms. These have been described cogently by Klerman (1985, 1991) and

include en-hancing the patient’s self-esteem, creating a safe environment in

which emotions are more freely discussed, reducing the stigma of seeking mental

health care through a positive placebo effect, im-proving cognition

(verbalization and abreaction), and functioning as a transitional object during

breaks in therapy, among others.

The

benefits of employing psychotherapy within a primarily psychopharmacologic

relationship have also been described. Empirical evidence exists across the

spectrum of mental health disorders to support the following suggested benefits

of adding psychotherapy to medications. It decreases the incidence of illness

relapse (Hogarty et al., 1986), as

well as symptom relapse upon medication discontinuation (Wiborg and Dahl, 1996;

Spiegel et al., 1994). It fosters the

patient’s ability to utilize healthy coping

strategies, addresses issues that are not typically targeted by

psychopharmacologic treatment such as dysfunctional relationship patterns or

negative self-appraisals due to traumatic past events, and enhances

psychotropic compliance (Paykel, 1995; Cochran, 1984).

Clinical Applications: Treatment Adherence

Adherence

may be enhanced in part through discussion of the patient’s metaphor for the

medication, either positive or negative (Kay, 2001).

The above

case highlights one of the beliefs that patients may have regarding

medications, that is, they indicate their provider’s level of interest in them

as a person and the provider truly appreciates the level of their distress. In

certain contexts these beliefs may be regarded as a “positive metaphor”;

however in others, as demonstrated above, it may hinder the patient’s response

to treatment, their compliance with the treatment regimen, and their level of

trust in their provider.

Clinical Applications: Sequential Treatment

Fava (1999) highlights that sequential treatments may be applied in four ways: 1) using a second type of psychotherapy when the first orientation has not fully achieved treatment goals; 2) introducing a second type of pharmacotherapy when the first medication has not achieved adequate symptom relief; 3) introducing psychotherapy when initial pharmacotherapy has not been fully effective; and 4) introducing pharmacotherapy when initial psychotherapy has not been fully effective. The latter two may include use of combined treatments in a sequential fashion.

As

demonstrated by the vignettes, the meanings that the patient attributes to

medication may have to do with cognitions and feelings in a variety of spheres

including the illness, the pro-vider, and themselves (Beck, 2001).

Clinical Applications: Advantages and Challenges

The

vignettes also serve to highlight potential benefits and chal-lenges

surrounding integrated treatment described by Kay (2001). Integrated treatment

essentially eliminates the communication difficulties encountered in split

treatment set-tings. The practitioner of integrated treatment does face some

obstacles. In both cases, the psychiatrist needs to be well trained in a

variety of psychotherapy orientations, particularly in the orienta-tion that

has evidence to support its use in a particular disorder.

To

provide a theoretical framework for formulation of the patient and treatment

plan, McHugh and Slavney (1983) similarly discuss understanding the

psychiatrically ill patient from four “perspectives”. These multifactorial

models of mental health illnesses serve as conceptual tools with which to

understand the whole patient and those forces that together precipitate,

perpetuate and modify illness course/progression. It stands to reason that a

provider of integrated care should utilize an “integrated” model of illness

description, etiology and treatment.

When a

single provider directs both forms of treatment, traditional role conflicts may

emerge. The role stereotype of a psychotherapist may include one who has a

multidimensional understanding of the patient, is interested in

intrapsychic/core conflicts and their manifestations in symptoms, behaviors,

feel-ings and thoughts, and whose style is less authoritarian. The

pharmacotherapist’s traditional role stereotype is of a biological/

neurochemical understanding of the patient and a prescriptive, structured, more

authoritarian style in approaching diagnosis, medications and other issues.

While these roles are, as described, stereotypic, they do have in common the

role of the provider in establishing rapport and a therapeutic alliance with

the patient. It has been suggested that the psychiatrist who uses an integrated

model provides more time for development of the therapeutic al-liance thus

increasing the patient’s comfort in disclosing embar-rassing side effects of

medication and, perhaps, even aiding in treatment outcome via the strength of

the alliance (Gabbard and Kay, 2001). Psychotherapy studies have suggested that

therapist variables accounted for 30% of the variance in outcomes, and that

therapeutic alliance is perhaps the most important factor in positive treatment

outcomes (Lambert, 1992; Svartberg et al.,

1998). The therapeutic alliance is crucial; as such, management of transitions

between roles, as well as the seamless integration of roles is imperative

within the practice of integrated treatment (Gabbard and Kay, 2001). These role

transitions may occur rap-idly and within a single session.

A

familiarity with current literature and clinical practice guidelines concerning

when to employ medications alone, ther-apy alone, or both, and when sequential

treatments may lead to a greater probability of remission is a must for any

clinician utiliz-ing combined treatment.

Clinical Applications: Managing the Session

This

example highlights one way in which to fluidly incorporate both domains

(psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy) within each patient visit. The above

approach is structured in nature, follow-ing cognitive therapy’s principle that

sessions are structured and remain constant during therapy (Beck, 1995).

Providers of psychodynamic therapy, among other types of therapy, often prefer

this structured type of approach, advocating that medica-tion use either be

discussed at the beginning or at the end of the session. Proponents of the

beginning method feel that discussion of medication issues ensures adequate

time is spent on concerns and may provide important material for the session.

Advocates of the “set aside 5 to 10 minutes at the end of the session” ap-proach

feel that it is most important for the patients to set their own agenda, as

this allows for time needed for the patient to regain composure/recompensate

before the end of the session. Another approach is the nonstructured method. In

this case the therapist addresses medication issues only when the need arises.

As there are no evidence-based studies to guide clini-cal practice, it is most

important to base the choice on patient and provider preference and to practice

consistency with each patient (Kay, 2002).

Clinical Applications: Individualizing Treatment

How can

the psychiatrist tailor his/her treatment options to each individual patient?

When would sequential approaches be indicated and in which disorders are

combined treatments most likely to be helpful? During which phase of treatment

(acute versus maintenance) should combined treatments be used versus solo

treatments (either medications or therapy)? For what severity of illness are

combined treatments pre-ferred? Is there evidence to support sequential

approaches and should they be specifically targeted to stages of the illness?

How might understanding physiologic changes in the brain, which occur in the

context of both medications and psycho-therapy, help guide our research and

clinical treatment inter-ventions? It should be kept in mind that research regarding

these issues is in its infancy, and many recommendations may require further

studies definitively to aid with the establish-ment of critical pathways for

each of the disorders In spite of the need for further research, combined

treatment appears useful for all major categories of psychotic illness,

including anxiety and mood disorders, psychotic disorders, eating disor-ders

and substance abuse.

Split Treatment

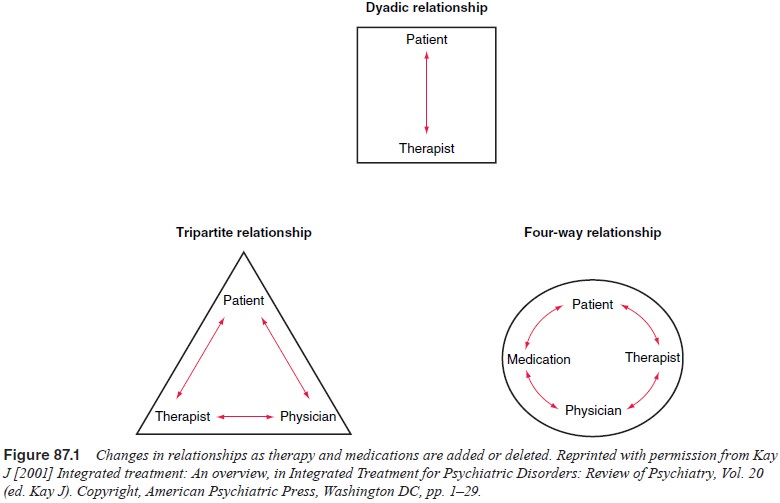

The last

few decades have seen an increasing shift from a single relationship between patient

and psychiatrist towards a tripartite relationship with the inclusion of

medication, or to a four-way or systemic relationship with the addition or

deletion of medications (Figure 87.1). Thus, combined treatments are commonly

provided by two or more clinicians, hence the term “split”.

Related Topics