Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Combined Therapies: Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

Negative Aspects

Negative

Aspects

Communication

While

communication is probably the most important factor in successful split

treatment, it is rarely done well (Hansen-Grant and Riba, 1995). Without a

systematic way for clinicians and the patient to have regular, documented

communication, there often arise misunderstandings and misconceptions. Further,

patients are sometimes put in the middle of having to be the messenger between

the clinicians. Needing to communicate puts additional burdens and stress on

busy clinicians with the telephone or in-person time not usually reimbursable.

Poor communication leads to misinter-pretation of what should be attributable

to psychodynamic issues or medication side effects, or both – a poorly

constructed treat-ment plan, ill-defined plans for discharge from treatment,

lack of coordination with family members, neither the clinician nor pa-tient

fully understanding vacation or coverage issues, and so on.

Interdisciplinary Issues

The

literature demonstrates that when clinicians know one an-other, they are more

comfortable with split treatment (Goldberg et

al., 1991; Weiner and Riba, 1997). Unfortunately, often the clinicians do not know one another,

which leads to basic mis-trust, competition, or inequality in the relationship

(Baggs and Schmitt, 1988). Further, this devaluation can be displaced onto the

patient during critical treatment decisions, with certain pa-tients exploiting

this competition even further (Kelly, 1991). The psychotherapy skills of

psychiatrists and nonmedical therapists and the psychopharmacologic education

of social workers and psychologists are all highly variable, contributing to

mistrust (Neal and Calarco, 1999). In such circumstances, the patient may

actually be seen more often by both clinicians and have ill-defined treatment

goals.

Transference and Countertransference

When

patients are referred by their therapists for medication evaluations, the

reactions are variable, but often negative. Such reactions include feeling

abandoned or rejected, as if the therapist has lost interest or given up, like

a failure because therapy did not work, devaluation of the psychotherapy and

the therapist, ideali-zation of the physician, shame, resistance to further

psychody-namic exploration of issues and a narcissistic injury (Busch and

Gould, 1993). Busch and Gould note the difficulties for the thera-pist who

needs to make the referral: shame that help is needed and anger towards the

patient for needing additional help. The psychiatrist could then collude with

the patient’s negative trans-ference towards the therapist and the

psychodynamic process.

Results

of such negative transference could lead to premature closure within the

therapeutic process (Bradley, 1990). There may be a flight into health by the

patient when the medication is first prescribed. The patient and physician may

then realize too late that there was an overreliance on biologic interventions.

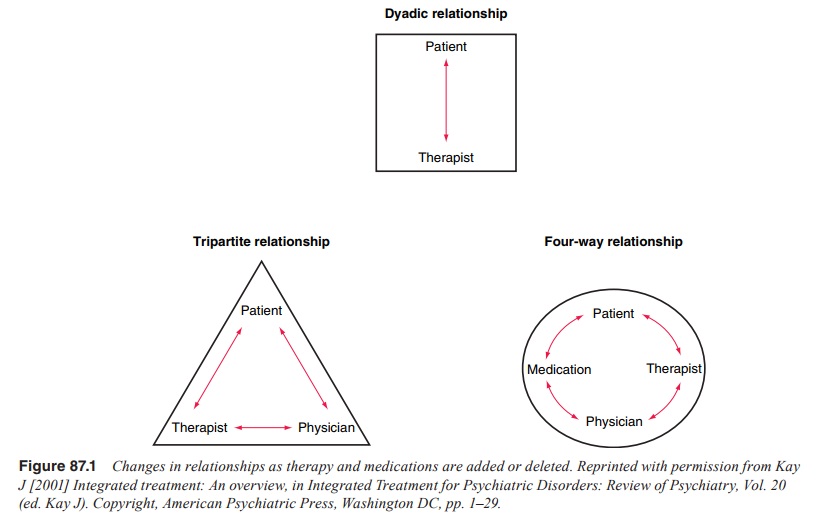

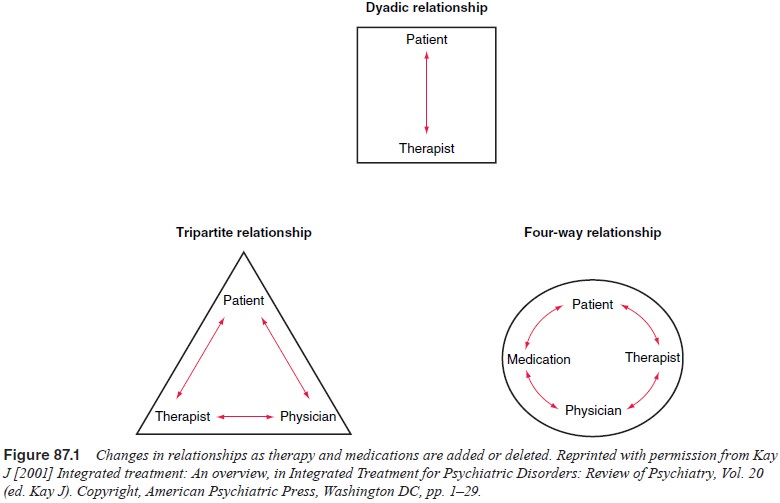

The dyadic relationship between the therapist and patient is changed with the

addition of a physician and medication (see Figure 87.1) leading to distortions

and transference changes in all the relationships.

Related Topics