Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Antipsychotic Drugs

Treatment of Different Phases of Schizophrenia

Treatment

of Different Phases of Schizophrenia

Treatment During the Acute Phase

Route of Administration

In

clinical situations, antipsychotic medications can be adminis-tered in oral

forms, including oral tablets, oral liquid concentrates and orally dissolving

formulations, as short-acting intramuscular preparations, or as long-acting

depot preparations (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In most cases,

patients who are cooperative prefer oral administration to parenteral medications.

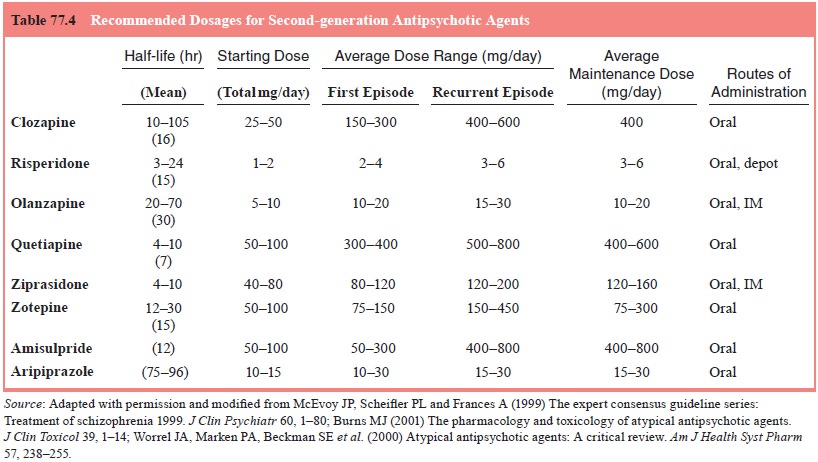

A summary of dosing recommendations for newer agents is pro-vided in Table

77.4. Oral antipsychotic medications tend to be rapidly and well absorbed from

the gastrointestinal tract, and reach a peak plasma concentration in 1 to 10

hours (Burns, 2001). The long average half-life (12–24 hours) and active

metabolites of most oral antipsychotic drugs allow for once- to twice-daily

dos-ing (Marder, 1997; Burns, 2001). Among the second-generation agents,

quetiapine and ziprasidone have relatively shorter half-lives (Table 77.4), and

should be administered in divided doses (Markowitz et al., 1999). A single or twice-daily dose of an oral preparation

will result in steady-state blood levels in 2 to 5 days (Dahl, 1990).

Short-acting

intramuscular (IM) medications are particu-larly useful in the management of

acute pathologic excitement and agitation (Buckley, 1999). The main indication

for the use of a short-acting parenteral form in the acute situation is to

treat severely disturbed patients who cannot be verbally redirected, who may be

violent, and who may have to be medicated over objection. Short-acting IM

preparations can reach a peak con-centration 30 to 60 minutes after the

medication is administered (Dahl, 1990).

Selection of an Antipsychotic Agent

Selection of an agent in emergency settings for the management of the gross agitation, excitement and violent behavior associated with psychosis might be based on clinical symptoms, differences in efficacy or side effects of candidate drugs, or, more pragmati-cally, the formulation of a drug as it affects route of administra-tion, onset and duration (Hirsch and Barnes, 1995; Allen, 2000). Most agitated patients will assent to oral medication and, in a survey of 51 psychiatric emergency services, the medical doctors estimated that only 10% of emergency patients require injectable medications (Currier, 2000). Practice and legal requirements concerning injectable medications differ substantially across the globe. The US Health Care Finance Administration’s (HCFA) regulations regarding so-called “chemical restraint” call for it to be a last resort, which would suggest that oral medication should be offered whenever it is possible to speak with the patient (Allen, 2000). Intramuscular treatments, however, remain nec-essary for some agitated or aggressive patients who refuse oral medications of any kind (Allen et al., 2001). In these situations, many clinicians avoid high doses on antipsychotic medications in favor of a combination of an antipsychotic and a benzodiazepine (Miyamoto et al., 2002b).

Dose of Antipsychotic Agent

Effective Doses of First-generation Antipsychotics The goal of pharmacotherapy is to maximize

efficacy and minimize ad-verse effects with the lowest effective dose. When

groups of pa-tients are assigned to higher doses, such as more than 2000 mg

chlorpromazine or 40 mg haloperidol equivalent, the rate and amount of

improvement are no greater than for those assigned to more moderate doses

(Marder, 1996).

Effective Doses of Second-generation Antipsychotics

The dosage recommendations for

second-generation antipsychotic drugs are summarized in Table 77.4. Although

clinical trial data show that second-generation antipsychotics are efficacious

and cause fewer EPS than the conventional agents, optimal dosing constitutes a

critical issue in their effective use.

Treatment Resistance

Patients

with schizophrenia may manifest poor response to treatment because of

intolerance to medication, poor compliance, inappropriate dosing, as well as

true resistance of their illness to antipsychotic medications. It has been

consistently reported

that

approximately 10 to 15% of patients with first-episode schizophrenia are

resistant to drug treatment (Lieberman et

al., 1993), and between 30 to 60% of patients become only partially

responsive or completely unresponsive to treatment during the course of the

illness (Davis and Casper, 1977; Essock et

al., 1996; Lieberman, 1999). Before a patient is considered

treatment-resistant, an optimized medication and treatment trial should be

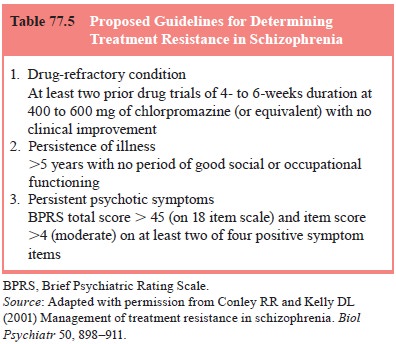

employed (Conley and Kelly, 2001). The most accepted criteria for defining

treatment resistance in schizophrenia were initially utilized by Kane and

collaborators (1988) in the Multicenter Clozapine Trial (MCT), and the modified

criteria have been used to define treatment resistance (Table 77.5). Although

most definitions of treatment resistance focus on the persistence of positive

symptoms, there is growing awareness of the problems of persistent negative

symptoms and cognitive impairments, which may have an important impact on level

of functioning, psychosocial integration and quality of life (Conley and Kelly,

2001; Peuskens, 1999).

Only

clozapine has consistently demonstrated efficacy for psychotic symptoms in

well-defined treatment refractory patients. The mechanism responsible for this

therapeutic ad-vantage remains uncertain. Thus, clozapine remains the “gold

standard” for treatment of this patient population. The evidence is strongest

in support of clozapine monotherapy as an interven-tion for treatment-resistant

patients; serum levels of 350 µg/mL or

greater have been associated with maximal likelihood of re-sponse (Miller,

1996).

Since the

approval of clozapine, attention has shifted to a greater focus on the use of

other second-generation antipsychot-ics for managing treatment resistance in

schizophrenia, but the relative efficacy of other second-generation

antipsychotics is less clear.

Given the

risk of agranulocytosis, the burden of side ef-fects and the requirement of

white blood cell monitoring, the second-generation agents (risperidone,

olanzapine, quetiapine and ziprasidone) should be tried before proceeding to

clozapine in almost all patients (Conley and Kelly, 2001; Miyamoto et al., 2002a). Many clinicians express

the impression that certain pa-tients do respond preferentially to a single

agent of this class. Sequential controlled trials of the newer agents in

treatment-resistant patients will be necessary fully to examine this issue.

Treatment During the Resolving Phase

During

the resolving phase, the goals of treatment are to minimize stress on the

patient, to facilitate the patient’s return to community life, and to establish

a long-term maintenance plan (Marder, 1999; American Psychiatric Association,

2000). If a particular antipsy-chotic medication has improved the acute

symptoms, it should be continued at the same dose for the next 6 months, before

a lower maintenance dose is considered for continued treatment (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000). Rapid dose reduction or discontin-uation of the

medications during the resolving phase may result in relatively rapid relapse

(American Psychiatric Association, 2000). If the psychiatrist has decided to

switch the therapy to a long-acting depot antipsychotic agent, this can often

be accompanied during this phase. This may also be a reasonable time to educate

the patient and family regarding the course and outcome of schizo-phrenia, as

well as factors that influence the outcome such as drug compliance (Marder,

1997; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Patients should be helped to

begin formulating a rehabilita-tion plan through realistic goal setting

(Marder, 1997).

Treatment During the Stable Phase (Maintenance Treatment)

The goals

of treatment during the stable or maintenance phase are to maintain symptom

remission, to prevent psychotic relapse, to implement a plan for rehabilitation

and to improve the patient’s quality of life (Marder, 1999; American

Psychiatric Associations, 2000). Current guidelines recommend that

first-episode patients should be treated for 1 to 2 years; however, 75% of

patients will have relapses after their treatment is discontinued (Kissling,

1991; Davis et al., 1994; Lehman and

Steinwachs, 1998; Ameri-can Psychiatric Association, 2000). Patients who have

had mul-tiple episodes should receive at least 5 years of maintenance therapy

(Kissling, 1991; Davis et al., 1994;

American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Patients with severe or dangerous

episodes should probably be treated indefinitely (American Psychiatric

Association, 2000).

For

conventional antipsychotics, the risk of long-term side effects such as the

development of TD inspired a search for strategies to reduce patients’ exposure

to these agents, and strate-gies for preventing relapse during the maintenance

phase has fo-cused on finding dosages that minimize drug adverse effects and

provide adequate protection against psychotic relapse (Marder, 1999).

Maintenance studies of the dose–response relationship found that lowering the

dose prescribed for acute treatment by about 80% may be relatively safe for

maintenance, although re-lapse rates are excessively high when doses are

reduced to about 10% of an acute dose (Marder et al., 1987; Hogarty et al.,

1988; Kane et al., 1983). The

international consensus conference rec-ommended a gradual reduction in

antipsychotic dose of approxi-mately 20% every 6 months until a minimal

maintenance dose is reached (Kissling, 1991).

Related Topics