Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : A Simple Syntax-Directed Translator

Syntax-Directed Translation

Syntax-Directed Translation

1 Postfix Notation

2 Synthesized Attributes

3 Simple Syntax-Directed

Definitions

4 Tree Traversals

5 Translation Schemes

6 Exercises for Section 2.3

Syntax-directed translation is done by attaching rules or program

fragments to productions in a grammar. For example, consider an expression expr generated by the production

expr -» exprx + term

Here, expr is the sum of the two

subexpressions exprx and term. (The subscript in exprx is used

only to distinguish the instance of expr in the production body from the head of the

production). We can translate

expr by exploiting its structure,

as in the following pseudo-code:

translate exprx;

translate term;

handle +;

Using a variant of this pseudocode, we shall build a syntax tree for expr in Section 2.8 by building syntax

trees for exprt and term and then handling +

by constructing a node for it. For convenience, the example in this section is

the translation of infix expressions into postfix notation.

This section introduces two concepts related to syntax-directed

translation:

• Attributes. An attribute is any quantity

associated with a programming construct.

Examples of attributes are data types of expressions, the num-ber of

instructions in the generated code, or the location of the first in-struction

in the generated code for a construct, among many other pos-sibilities. Since

we use grammar symbols (nonterminals and terminals) to represent programming

constructs, we extend the notion of attributes from constructs to the symbols

that represent them.

• (Syntax-directed) translation schemes. A

translation scheme is a notation for

attaching program fragments to the productions of a grammar. The program

fragments are executed when the production is used during syn- tax analysis. The combined result of all these fragment

executions, in the order induced by the

syntax analysis, produces the translation of the program to which this

analysis/synthesis process is applied.

Syntax-directed translations will be used throughout this chapter to

trans-late infix expressions into postfix notation, to evaluate expressions,

and to build syntax trees for programming constructs. A more detailed

discussion of syntax-directed formalisms appears in Chapter 5.

1. Postfix Notation

The examples in this section deal with translation into postfix

notation. The postfix notation for an

expression E can be defined inductively

as follows:

1. If E is a variable or

constant, then the postfix notation for E

is E itself.

2. If E is an expression of

the form E1 op E2, where op is any binary operator, then the postfix notation for E is E[ E'2 op, where E[ and E'2 are the

postfix notations for E1 and E2, respectively.

3. If E is a parenthesized expression of the

form (Ei), then the postfix notation

for E is the same as the postfix

notation for E1.

E x a m p l e 2.8 : The postfix notation for (9 -

5)+2 is 95-2+. That is, the trans-lations

of 9, 5, and 2 are the constants themselves, by rule (1). Then, the translation of 9-5

is 95 - by rule (2). The translation of (9 -

5) is the same by rule (3).

Having translated the parenthesized subexpression, we may apply rule (2) to the

entire expression, with (9 - 5) in the

role of E1 and 2 in the role of E2: to get the result 95-2+.

As another example, the postfix notation for 9- (5+2) is 952+-. That

is, 5+2 is first translated into 52+, and this expression becomes the

second argument of the minus sign. •

No parentheses are needed in postfix notation, because the position and arity (number of arguments) of the

operators permits only one decoding of a postfix

expression. The "trick" is to repeatedly scan the postfix string from

the left, until you find an operator. Then, look to the left for the proper

number of operands, and group this operator with its operands. Evaluate the

operator on the operands, and replace them by the result. Then repeat the

process, continuing to the right and searching for another operator.

E x a m p l e 2 . 9 : Consider the postfix expression

952+-3*. Scanning from the left,

we first encounter the plus sign. Looking to its left we find operands 5 and 2. Their sum, 7, replaces 52+, and we have the string 97 - 3* . Now, the leftmost operator

is the minus sign, and its operands are 9

and 7. Replacing these by the result

of the subtraction leaves 23*. Last,

the multiplication sign applies to 2 and 3, giving the result 6. •

2. Synthesized Attributes

The idea of associating quantities with programming constructs—for

example, values and types with expressions—can be expressed in terms of

grammars. We associate attributes with nonterminals and terminals. Then, we

attach rules to the productions of the grammar; these rules describe how the

attributes are computed at those nodes of the parse tree where the production

in question is used to relate a node to its children.

A syntax-directed definition associates

1. With each grammar symbol, a

set of attributes, and

2. With each production, a set of semantic

rules for computing the values of the attributes associated with the

symbols appearing in the production.

Attributes can be evaluated as follows. For a given input string x, construct a parse tree for x. Then, apply the semantic rules to

evaluate attributes at each node in the parse tree, as follows.

Suppose a node A?" in a parse tree is labeled by the grammar symbol

X. We write X.a to denote the value of attribute a of X at that node. A

parse tree showing the attribute values at each node is called an annotated parse tree. For example, Fig. 2.9 shows an annotated parse tree for 9-5+2 with an attribute t associated with the nonterminals expr and term. The value 95-2+ of the attribute at the

root is the postfix notation for 9-5+2.

We shall see shortly how these

expressions are computed.

An attribute is said to be synthesized

if its value at a parse-tree node N

is de-termined from attribute values at the children of N and at N itself.

Synthesized attributes have the desirable property that they can be evaluated

during a sin-gle bottom-up traversal of a parse tree. In Section 5.1.1 we shall

discuss another important kind of attribute: the "inherited"

attribute. Informally, inherited at-tributes have their value at a parse-tree

node determined from attribute values at the node itself, its parent, and its

siblings in the parse tree.

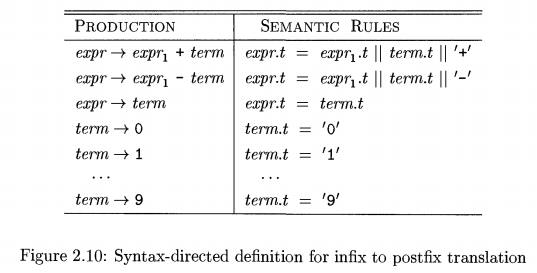

Example 2 . 1 0 : The annotated parse tree in Fig. 2 . 9 is based on the syntax-directed

definition in Fig. 2 . 1 0 for translating expressions consisting of digits

separated by plus or minus signs into postfix notation. Each nonterminal has a

string-valued attribute t that

represents the postfix notation for the expression generated by that

nonterminal in a parse tree. The symbol || in the semantic rule is the operator

for string concatenation.

The postfix form of a digit is the digit itself; e.g., the semantic rule

associ-ated with the production term -» 9 defines term.t to be 9 itself

whenever this production is used at a node in a parse tree. The other digits

are translated similarly. As another

example, when the production expr term is applied, the value of term.t becomes the value of

expr.t.

The production expr —> exprx + term derives an expression containing

a plus operator.3 The left operand of the plus operator is given by exprx and the

right operand by term. The semantic

rule

expr.t = expr.t

\\ term.t \\ '+'

associated with this production constructs the value of attribute expr.t by con-catenating the postfix

forms expr.t and term.t of the left and right operands, respectively, and then

appending the plus sign. This rule is a formalization of the definition of

"postfix expression." •

Convention Distinguishing Uses of

a Nonterminal

In rules, we often have a need to distinguish among several uses of the

same nonterminal in the head and/or body of a production; e.g., see Ex-ample

2.10. The reason is that in the parse tree, different nodes labeled by the same

nonterminal usually have different values for their transla-tions. We shall

adopt the following convention: the nonterminal appears unsubscripted in the

head and with distinct subscripts in the body. These are all occurrences of the

same nonterminal, and the subscript is not part of its name. However, the

reader should be alert to the difference be-tween examples of specific

translations, where this convention is used, and generic productions like A —> X1X2, • • • ,Xn, where

the subscripted X ' s represent an arbitrary list of grammar symbols, and are not instances of one particular

nonterminal called X.

3. Simple Syntax-Directed

Definitions

The syntax-directed definition in Example 2.10 has the following

important property: the string representing the translation of the nonterminal

at the head of each production is the concatenation of the translations of the

nonterminals in the production body, in the same order as in the production,

with some optional additional strings interleaved. A syntax-directed definition

with this property is termed simple.

E x a m p l e 2 . 1 1 : Consider the first production

and semantic rule from Fig. 2.10:

P R O D U C T I O N S E M A N T I C R U L E

(2.5)

expr^r exprx + term expr.t = exprx.t || term.t

|| '+'

Here the translation expr.t is

the concatenation of the translations of exprx and term, followed by the

symbol +. Notice that expr1 and term appear in the same order in both the production body and the semantic rule.

There are no additional symbols before or between their translations. In this

example, the only extra symbol occurs at the end. •

When translation schemes are discussed, we shall see that a simple

syntax-directed definition can be implemented by printing only the additional

strings, in the order they appear in the definition.

4. Tree Traversals

Tree traversals will be used for describing attribute evaluation and for

specifying the execution of code fragments in a translation scheme. A traversal of a tree starts at the root

and visits each node of the tree in some order.

A depth-first traversal starts at

the root and recursively visits the children of each node in any order,

not necessarily from left to right. It

is called "depth-first" because it visits an unvisited child of a

node whenever it can, so it visits nodes as far away from the root (as

"deep") as quickly as it can.

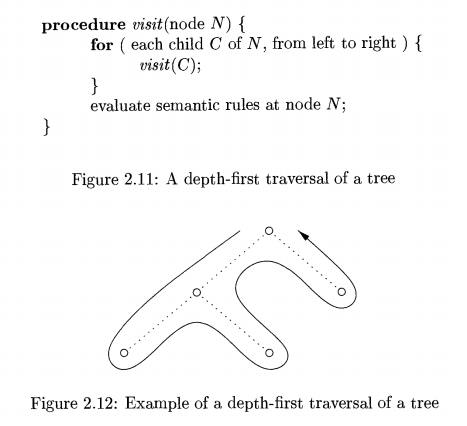

The procedure visit(N) in Fig.

2.11 is a depth first traversal that visits the children of a node in

left-to-right order, as shown in Fig. 2.12. In this traversal, we have included

the action of evaluating translations at each node, just before we finish with

the node (that is, after translations at the children have surely been

computed). In general, the actions associated with a traversal can be

whatever we choose, or nothing at all.

A syntax-directed definition does not impose any specific order for the

eval-uation of attributes on a parse tree; any evaluation order that computes

an attribute a after all the other attributes that a depends on is acceptable. Syn-thesized attributes can be evaluated

during any bottom-up traversal, that

is, a traversal that evaluates attributes at a node after having evaluated

attributes at its children. In general, with both synthesized and inherited

attributes, the matter of evaluation order is quite complex; see Section 5.2.

5. Translation Schemes

The syntax-directed definition in Fig. 2.10 builds up a translation by

attaching strings as attributes to the nodes in the parse tree. We now consider

an alter-native approach that does not need to manipulate strings; it produces

the same translation incrementally, by executing program fragments.

Preorder and Postorder Traversals

Preorder and postorder traversals are two important special cases of

depth-first traversals in which we visit the children of each node from left to

right.

Often, we traverse a tree to

perform some particular action at each node. If

the action is done when we first visit a node, then we may refer to the

traversal as a preorder traversal.

Similarly, if the action

is done just before we leave a

node for the last time, then we say it is a postorder traversal of the tree.

The procedure visit(N) in Fig. 2.11 is an example of a postorder traversal.

Preorder and postorder traversals define corresponding orderings on

nodes, based on when the action at a node would be performed. The preorder of a (sub)tree rooted at node

JV consists of N, followed by the preorders of the subtrees of each of

its children, if any, from the left. The postorder

of a (sub)tree rooted at TV" consists of the postorders of each of the subtrees for the children of N, if any, from the left, followed by N itself.

A syntax-directed translation scheme is a notation for specifying a

transla-tion by attaching program fragments to productions in a grammar. A

transla-tion scheme is like a syntax-directed definition, except that the order

of evalu-ation of the semantic rules is explicitly specified.

Program fragments embedded within production bodies are called semantic actions. The position at which an action is to be executed is shown

by enclosing it between curly braces

and writing it within the production body, as in

rest —> + term {print('+')} rest\

We shall see such rules when we consider an alternative form of grammar

for expressions, where the nonterminal rest

represents "everything but the first term of an expression." This

form of grammar is discussed in Section 2.4.5. Again, the subscript in rest\ distinguishes this instance of

nonterminal rest in the production

body from the instance of rest at the

head of the production.

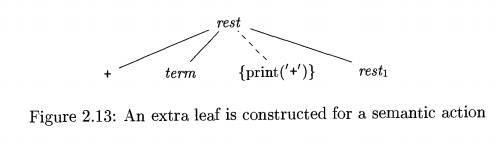

When drawing a parse tree for a translation scheme, we indicate an

action by constructing an extra child for it, connected by a dashed line to the

node that corresponds to the head of the production. For example, the portion

of the parse tree for the above production and action is shown in Fig. 2.13.

The node for a semantic action has no children, so the action is performed when

that node is first seen.

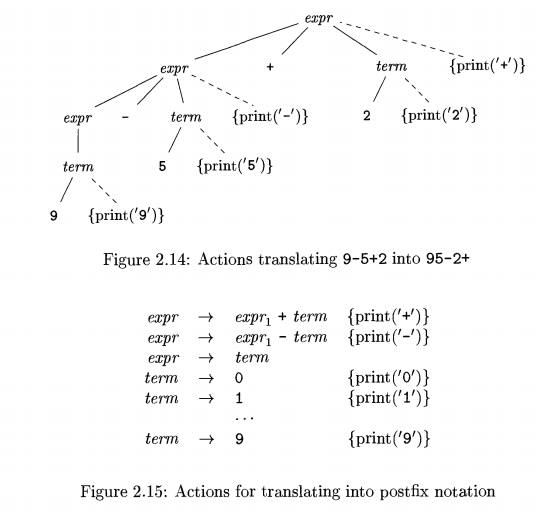

E x a m p l e 2 . 1 2 : The parse tree in Fig. 2.14 has print statements at extra leaves, which are attached by dashed

lines to interior nodes of the parse tree. The translation scheme appears in

Fig. 2.15. The underlying grammar gen-erates expressions consisting of digits

separated by plus and minus signs. The

actions embedded in the production bodies translate such expressions

into post-fix notation, provided we perform a left-to-right depth-first

traversal of the tree and execute each print statement when we visit its leaf.

The root of Fig. 2.14 represents the first production in Fig. 2.15. In a

postorder traversal, we first perform all the actions in the leftmost subtree

of the root, for the left operand, also labeled expr like the root. We then

visit the leaf + at which there is no action. We next perform the actions in

the subtree for the right operand term and, finally, the semantic action {

print('+') } at the extra node.

Since the productions for term have only a digit on the right side, that

digit is printed by the actions for the productions. No output is necessary for

the production expr -> term, and only the operator needs to be printed in

the action for each of the first two productions. When executed during a

postorder traversal of the parse tree, the actions in Fig. 2.14 print 95-2+. •

Note that although the schemes in Fig. 2.10 and Fig. 2.15 produce the

same translation, they construct it differently; Fig. 2.10 attaches strings as

attributes to the nodes in the parse tree, while the scheme in Fig. 2.15 prints

the translation incrementally, through semantic actions.

The semantic actions in the parse tree in Fig. 2.14 translate the infix

ex-pression 9-5+2 into 95-2+ by printing each character in 9-5+2 exactly once,

without using any storage for the translation of subexpressions. When the

out-put is created incrementally in this fashion, the order in which the

characters are printed is significant.

The implementation of a translation scheme must ensure that semantic

ac-tions are performed in the order they would appear during a postorder

traversal of a parse tree. The implementation need not actually construct a

parse tree (often it does not), as long as it ensures that the semantic actions

are per-formed as if we constructed a parse tree and then executed the actions

during a postorder traversal.

6. Exercises for Section 2.3

Exercise 2 . 3 . 1 : Construct a syntax-directed translation scheme that trans-lates

arithmetic expressions from infix notation into prefix notation in which an

operator appears before its operands; e.g., —xy

is the prefix notation for x — y.

Give annotated parse trees for the inputs 9-5+2 and 9-5*2.

Exercise 2 . 3 . 2: Construct a syntax-directed translation scheme that trans-lates

arithmetic expressions from postfix notation into infix notation. Give

annotated parse trees for the inputs 95 - 2* and 952* - .

Exercise 2 . 3 . 3: Construct a syntax-directed translation scheme that trans-lates integers

into roman numerals.

Exercise 2 . 3 . 4: Construct a syntax-directed translation scheme that trans-lates roman

numerals into integers.

Exercise 2 . 3 . 5: Construct a syntax-directed translation scheme that trans-lates postfix

arithmetic expressions into equivalent infix arithmetic expressions.

Related Topics