Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : A Simple Syntax-Directed Translator

Lexical Analysis

Lexical Analysis

1 Removal of White Space and

Comments

2 Reading Ahead

3 Constants

4 Recognizing Keywords and

Identifiers

5 A Lexical Analyzer

6 Exercises for Section 2.6

A lexical analyzer reads characters from the input and groups them into

"token objects." Along with a terminal symbol that is

used for parsing decisions, a token

object carries additional information in the form of attribute values.

So far, there has been no need

to distinguish between the

terms "token" and "terminal," since the parser

ignores the attribute values that are carried by a token. In this section, a

token is a terminal along with additional information.

A sequence of input characters that comprises a single token is called a

lexeme. Thus, we can say that the lexical analyzer insulates a parser from the

lexeme representation of tokens.

The lexical analyzer in this section allows numbers, identifiers, and

"white space" (blanks, tabs, and newlines) to appear within

expressions. It can be used to extend the expression translator of the previous

section. Since the expression grammar of Fig. 2.21 must be extended to allow

numbers and identifiers, we shall take this opportunity to allow multiplication

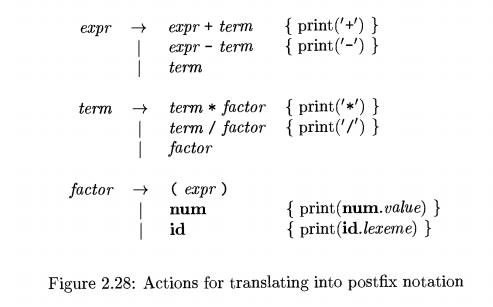

and division as well. The extended translation scheme appears in Fig. 2.28.

In Fig. 2.28, the terminal n u m is assumed

to have an attribute imm.value, which gives the integer value corresponding to

this occurrence of num . Termi-nal id has a string-valued attribute written as

id.lexeme; we assume this string is the actual lexeme comprising this instance

of the token id.

The pseudocode fragments used to illustrate the workings of a lexical

ana-lyzer will be assembled into Java code at the end of this section. The

approach in this section is suitable for hand-written lexical analyzers.

Section 3.5 de-scribes a tool called Lex that generates a lexical analyzer from

a specification. Symbol tables or data structures for holding information about

identifiers are considered in Section 2.7.

1. Removal of White Space and

Comments

The expression translator in Section 2.5 sees every character in the input,

so extraneous characters, such as blanks, will cause it to fail. Most languages

allow arbitrary amounts of white space to appear between tokens. Comments are

likewise ignored during parsing, so they may also be treated as white space.

If white space is eliminated by the lexical analyzer, the parser will

never have to consider it. The alternative of modifying the grammar to

incorporate white space into the syntax is not nearly as easy to implement.

The pseudocode in Fig. 2.29 skips white space by reading input

characters as long as it sees a blank, a tab, or a newline. Variable peek holds the next input character.

Line numbers and context are useful within error messages to help pinpoint

errors; the code uses variable line

to count newline characters in the input.

2. Reading Ahead

A lexical analyzer may need to read ahead some characters before it can

decide on the token to be

returned to the parser. For example, a lexical analyzer for C or Java must read ahead after it sees the character >. If the next character is =,

then > is part of the character sequence >=, the lexeme for the token for

the "greater than or equal to" operator. Otherwise > itself forms

the "greater than" operator, and the lexical analyzer has read one

character too many.

A general approach to reading ahead on the input, is to maintain an

input buffer from which the lexical analyzer can read and push back characters.

Input buffers can be justified on efficiency grounds alone, since fetching a

block of characters is usually more efficient than fetching one character at a

time. A pointer keeps track of the portion of the input that has been analyzed;

pushing back a character is implemented by moving back the pointer. Techniques

for input buffering are discussed in Section 3.2.

One-character read-ahead usually suffices, so a simple solution is to

use a variable, say peek, to hold the

next input character. The lexical analyzer in this section reads ahead one

character while it collects digits for numbers or characters for identifiers;

e.g., it reads past 1 to distinguish between 1 and 10, and it reads past t to distinguish between t and true .

The lexical analyzer reads ahead only when it must. An operator like *

can be identified without reading ahead. In such cases, peek is set to a blank, which will be skipped when the lexical

analyzer is called to find the next token. The invariant assertion in this

section is that when the lexical analyzer returns a token, variable peek either holds the character beyond

the lexeme for the current token, or it holds a blank.

3. Constants

Anytime a single digit appears in a grammar for expressions, it seems

reasonable to allow an arbitrary integer constant in its place. Integer

constants can be allowed either by creating a terminal symbol, say num, for such constants or by

incorporating the syntax of integer constants into the grammar. The job of

collecting characters into integers and computing their collective numerical

value is generally given to a lexical analyzer, so numbers can be treated as

single units during parsing and translation.

W h en a sequence of digits appears in the input stream, the lexical

analyzer passes to the parser a token consisting of the terminal n u m along with an integer-valued

attribute computed from the digits. If we write tokens as tuples enclosed

between ( ), the input 31

+ 28 + 59 is transformed into the sequence

(num, 31) (+) (num, 28) (+) (num, 59)

Here, the terminal symbol + has no attributes, so its tuple is simply

(+). The pseudocode in Fig. 2.30 reads

the digits in an integer and accumulates the value of the integer using

variable v.

if ( peek holds a digit ) {

v = 0;

do {

v = v * 10 + integer value of digit peek;

peek = next input character;

} while ( peek holds a digit ); return token (num, v);

}

Figure 2.30: Grouping digits into

integers

4. Recognizing Keywords and

Identifiers

Most languages use fixed character strings such as for, do, and if, as

punctua-tion marks or to identify constructs. Such character strings are called

keywords.

Character strings are also used as identifiers to name variables,

arrays, func-tions, and the like. Grammars routinely treat identifiers as

terminals to sim-plify the parser, which can then expect the same terminal, say

id, each time any identifier appears

in the input. For example, on input

|

count =

count + increment; |

(2.6) |

the parser works with the terminal stream id = id + id. The token for id

has an attribute that holds the lexeme. Writing tokens as tuples, we see that

the tuples for the input stream (2.6)

are

(id, "count") (=) (id,

"count") (+) (id, "increment") (;)

Keywords generally satisfy the rules for forming identifiers, so a

mechanism is needed for deciding when a lexeme forms a keyword and when it

forms an identifier. The problem is easier to resolve if keywords are reserved; i.e., if they cannot be used

as identifiers. Then, a character string forms an identifier only if it is not

a keyword.

The lexical analyzer in this section solves two problems by using a

table to hold character strings:

• Single Representation. A string table can insulate the rest of the compiler from the representation of strings, since the phases of the

compiler can work with references or pointers to the string in the table.

References can also be manipulated more efficiently than the strings

themselves.

• Reserved Words. Reserved words can be implemented by initializing the string table with the reserved strings

and their tokens. When the lexical analyzer reads a string or lexeme that could

form an identifier, it first checks whether the lexeme is in the string table.

If so, it returns the token from the table; otherwise, it returns a token with

terminal id.

In Java, a string table can be implemented as a hash table using a class

called Hashtable. The declaration

Hashtable words = n e w HashtableQ;

sets up words as a default

hash table that maps keys to values. We shall use it to map lexemes to tokens.

The pseudocode in Fig. 2.31 uses the operation get to look up reserved words.

if ( peek holds a letter ) {

collect letters or digits into a

buffer 6;

s = string formed from the characters in 6;

w = token returned by words.get(s);

if ( w is not n u l l ) return w;

else {

Enter the key-value pair (s, (id, s)) into words

return token (id, s);

}

}

Figure 2.31: Distinguishing

keywords from identifiers

This pseudocode collects from the input a string s consisting of letters and digits beginning with a letter. We

assume that s is made as long as possible; i.e., the lexical analyzer will

continue reading from the input as long as it encounters letters and digits.

When something other than a letter or digit, e.g., white space, is encountered,

the lexeme is copied into a buffer 6. If the table has an entry for s, then the token retrieved by words.get is returned. Here, s could be either a keyword, with which

the words table was initially seeded,

or it could be an identifier that was previously entered into the table.

Otherwise, token id and attribute s are installed in the table and

returned.

5. A Lexical Analyzer

The pseudocode fragments so far in this section fit together to form a

function scan that returns token

objects, as follows:

Token scanQ {

skip white space, as in Section 2.6.1; handle numbers, as in Section

2.6.3;

handle reserved words and identifiers, as in Section 2.6.4;

/* if we get here, treat read-ahead character peek as a token */

Token t = n e w Token(peek);

peek = blank /* initialization, as

discussed in Section 2.6.2 */ ;

r e t u r n i;

}

The rest of this section implements function scan as part of a Java

package for lexical analysis. The package, called l e x e r has classes for

tokens and a class Lexer containing function

scan.

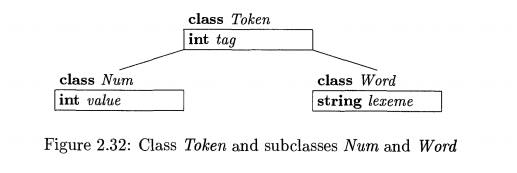

The classes for tokens and their

fields are illustrated in Fig.

2.32; their methods are not

shown. Class Token has a field t a

g that is used for parsing decisions.

Subclass Num adds a field v a l u e for an integer value. Subclass Word adds a field lexeme that is

used for reserved words and identifiers.

Each class is in a file by itself.

The file for class Token is as follows:

1) package lexer ; // File

Token.java

2) public class Token

{

3 ) public final int tag;

4) public Token (int t) { tag

= t; }

5) }

Line 1 identifies the package lexer.

Field t a g is declared on line 3

to be final so it cannot be changed once it is set. The constructor Token on

line 4 is used to create token objects, as in new Token ('+')

which creates a new object of class Token and sets its field tag to an

integer representation of ' + '. (For brevity, we omit the customary method t o

String , which would return a string suitable for printing.)

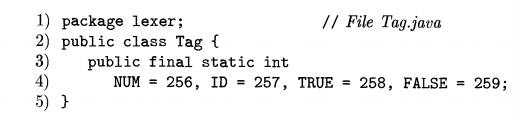

Where the pseudocode had

terminals like n u m and id, the Java code uses integer constants. Class Tag

implements such constants:

In addition to the integer-valued

fields NUM and ID, this class defines two addi-tional fields, TRUE and FALSE,

for future use; they will be used to illustrate the treatment of reserved

keywords.7

The fields in class Tag are public, so they can be used outside the package.

They are static , so there is

just one instance or copy of these

fields. The fields are final , so

they can be set just once. In effect, these fields represent constants. A similar

effect is achieved in C by using define-statements to allow names such as NUM

to be used as symbolic constants, e.g.:

#define NUM 256

The Java code refers to Tag. NUM

and Tag. ID in places where the pseudocode referred to terminals n u m and id.

The only requirement is that Tag.NUM and Tag. ID must be initialized with

distinct values that differ from each other and from the constants representing

single-character tokens, such as ' +' or ' *' .

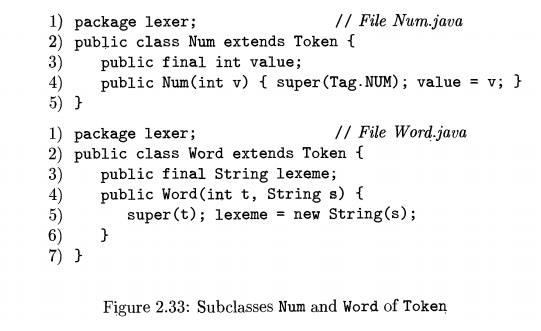

Classes Num and Word appear in

Fig. 2.33. Class Num extends Token by declaring an integer field value on line

3. The constructor Num on line 4 calls super (Tag. NUM), which sets field tag

in the superclass Token to Tag. NUM.

Class Word is used for both reserved words and identifiers, so the constructor Word on line 4 expects

two parameters: a lexeme and a corresponding integer value for

tag. An object for the reserved word true can be

created by executing

new Word(Tag.TRUE, "true")

which creates a new object with field tag set to Tag.TRUE and

field lexeme set to the string "true".

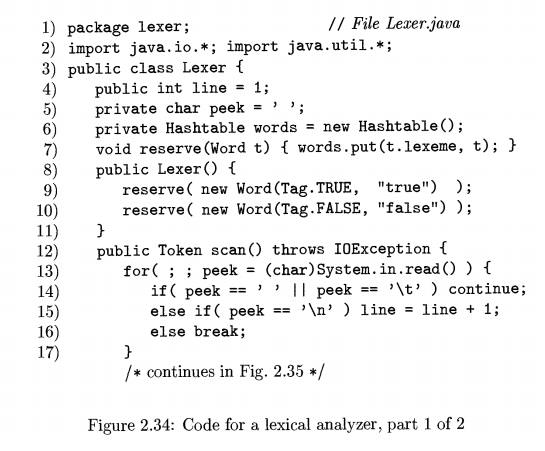

Class Lexer for lexical analysis appears in Figs. 2.34 and 2.35. The

integer variable line on line 4 counts input lines, and character variable peek on line 5 holds

the next input character.

Reserved words are handled on lines 6 through 11. The

table words is declared on line 6. The helper function reserve on line 7 puts a string-word pair in the table. Lines 9 and 10 in the

constructor Lexer initialize the table. They use the constructor Word to

create word objects, which are passed to the helper function reserve. The

table is therefore initialized with reserved words "true" and "false" before the first call of

scan.

The code for scan in Fig. 2.34-2.35 implements the pseudocode fragments in this section. The for-statement

on lines 13 through 17 skips blank, tab, and newline characters. Control leaves the

for-statement with peek holding a non-white-space character.

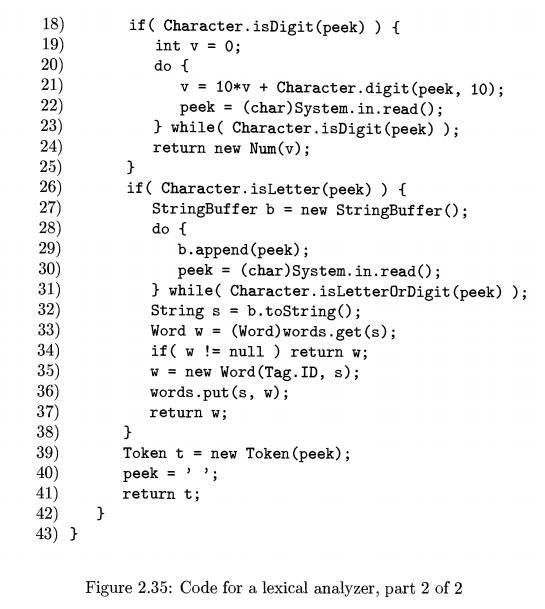

The code for reading a sequence of digits is on lines 18 through 25. The

function isDigit is from the built-in Java class Character. It is

used on line 18 to check whether peek is a digit. If so, the code on lines 19 through 24

accumulates the integer value of the sequence of digits in the input and

returns a new Num object.

Lines 26 through 38 analyze reserved words and

identifiers. Keywords true and false have already been reserved on

lines 9 and 10. Therefore, line 35

is reached if string s is not

reserved, so it must be the lexeme for an identifier. Line 35 therefore returns a new word object with lexeme set to s and tag set to Tag. ID. Finally, lines 39

through 41 return the current

character as a token and set peek to

a blank that will be stripped the next time scan is called.

6. Exercises for Section 2.6

Exercise 2 . 6 . 1 : Extend the lexical analyzer in Section 2.6.5 to remove com-ments, defined as follows:

A comment begins with // and

includes all characters until the end of that line.

A comment begins with /* and

includes all characters through the next occurrence of the character sequence

*/ .

E x e r c i s e 2 . 6 . 2 :

Extend the lexical analyzer in Section 2.6.5 to recognize the relational

operators <, <=, ==, !=, >=, >.

E x e r c i s e 2 . 6 . 3 :

Extend the lexical analyzer in Section 2.6.5 to recognize float-ing point

numbers such as 2 . , 3 . 14, and . 5.

Related Topics