Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: Integumentary System

Skin

Skin

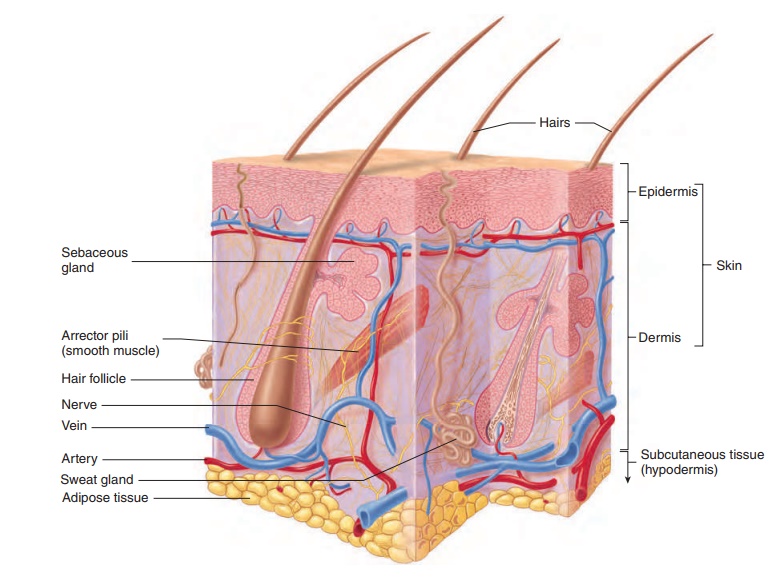

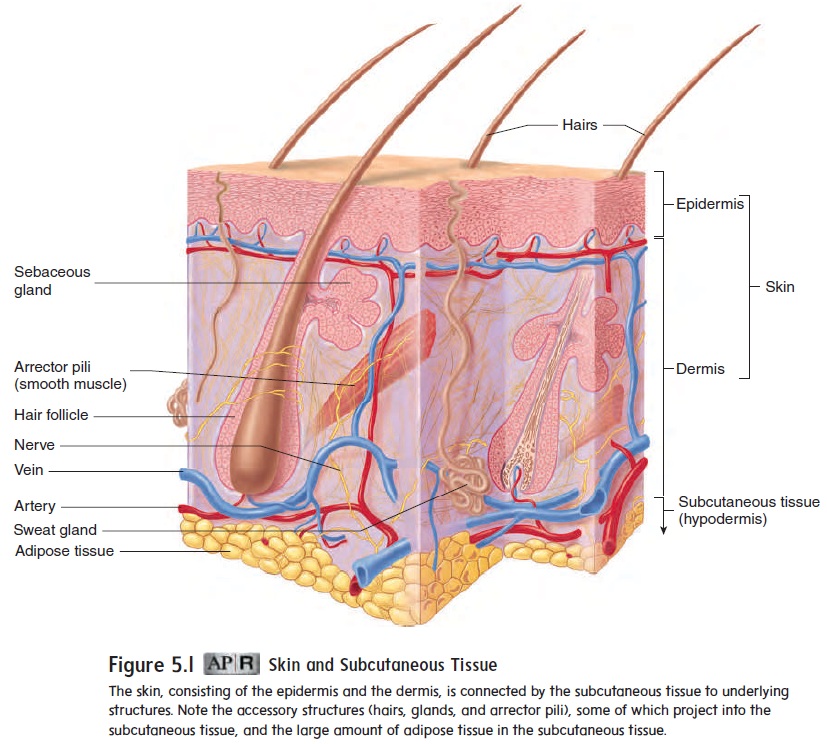

The skin is made up of two major tissue layers: the epidermis and the dermis. The epidermis (ep-i-der′\mis; upon the dermis) is the most superficial layer of skin. It is a layer of epithelial tissue that (figure 5.1). The thickness of the epidermis and dermis varies,rests on the dermis (der′mis), a layer of dense connective tissuedepending on location, but on average the dermis is 10 to 20 times thicker than the epidermis. The epidermis prevents water loss and resists abrasion. The dermis is responsible for most of the skin’s structural strength. The skin rests on the subcutaneous (sŭb-koo-tā′nē-ŭs; under the skin)tissue, which is a layer of connective tissue. The subcutaneous tissue is not part of the skin, but it does connect the skin to underlying muscle or bone. To give an analogy, if the subcutaneous tissue is the foundation on which a house rests, the dermis forms most of the house and the epidermis is its roof.

Epidermis

The epidermis is stratified squamous epithelium; in its deepest layers, new cells are produced by mitosis. As new cells form, they push older cells to the surface, where they slough, or flake off. The outermost cells protect the cells underneath, and the deeper, replicating cells replace cells lost from the surface. During their movement, the cells change shape and chemical composition. This process is calledkeratinization (ker′ă-tin-i-zā′shŭn) because the cells become filled with the protein keratin (ker′ă-tin), which makes them hard. As keratinization proceeds, epithelial cells eventually die and produce an outer layer of dead, hard cells that resists abrasion and forms a permeability barrier.

Figure 5.1Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

Although keratinization is a continuous process, distinct layers called strata (stra′tă ; layer) can be seen in the epidermis (figure 5.2). The deepest stratum, the stratum basale (bā ′să -lē ; a base), consists of cuboidal or columnar cells that undergo mitotic divisions about every 19 days. One daughter cell becomes a new stratum basale cell and can divide again. The other daughter cell is pushed toward the surface, a journey that takes about 40–56 days. As cells move to the surface, changes in the cells produce inter-mediate strata.

The stratum corneum (kō r′nē -ŭ m) is the most superficial stratum of the epidermis. It consists of dead squamous cells filled with keratin. Keratin gives the stratum corneum its structural strength. The stratum corneum cells are also coated and surrounded by lipids, which help prevent fluid loss through the skin.

Figure 5.2 Epidermis and Dermis

The stratum corneum is composed of 25 or more layers of dead squamous cells joined by desmosomes . Eventually, the desmosomes break apart, and the cells are sloughed from the skin. Excessive sloughing of stratum corneum cells from the sur-face of the scalp is called dandruff. In skin subjected to friction, the number of layers in the stratum corneum greatly increases, producing a thickened area called a callus(kal′ ̆u s; hard skin). Over a bony prominence, the stratum corneum can thicken to form a cone-shaped structure called a corn.

Dermis

The dermis is composed of dense collagenous connective tissue containing fibroblasts, adipocytes, and macrophages. Nerves, hair follicles, smooth muscles, glands, and lymphatic vessels extend into the dermis (see figure 5.1).

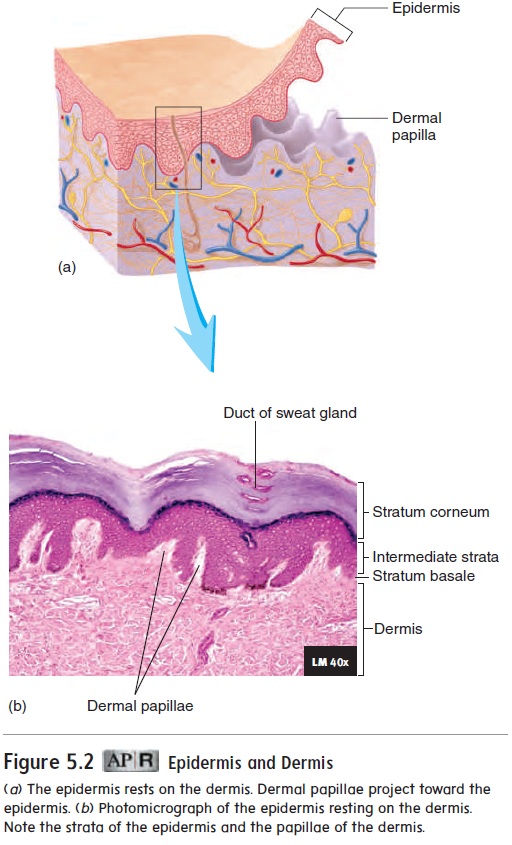

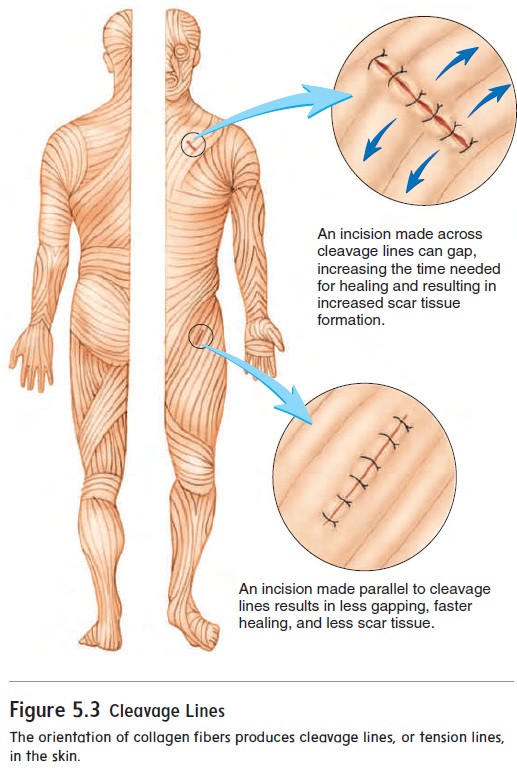

Collagen and elastic fibers are responsible for the structural strength of the dermis. In fact, the dermis is the part of an animal hide from which leather is made. The collagen fibers of the dermis are oriented in many different directions and can resist stretch. However, more collagen fibers are oriented in some directions than in others. This produces cleavage lines, or tension lines, in the skin, and the skin is most resistant to stretch along these lines (figure 5.3). It is important for surgeons to be aware of cleavage lines. An incision made across the cleavage lines is likely to gap and produce considerable scar tissue, but an incision made parallel with the lines tends to gap less and produce less scar tissue . If the skin is overstretched for any reason, the dermis can be damaged, leaving lines that are visible through the epidermis. These lines, called stretch marks, can develop when a person increases in size quite rapidly. For example, stretch marks often form on the skin of the abdomen and breasts of a woman during pregnancy or on the skin of athletes who have quickly increased muscle size by intense weight training.

The upper part of the dermis has projections called dermalpapillae (pă-pil′e; nipple), which extend toward the epidermis(see figure 5.2). The dermal papillae contain many blood vessels that supply the overlying epidermis with nutrients, remove waste products, and help regulate body temperature. The dermal papillae in the palms of the hands, the soles of the feet, and the tips of the digits are arranged in parallel, curving ridges that shape the overlying epidermis into fingerprints and footprints. The ridges increase friction and improve the grip of the hands and feet.

Figure 5.3 Cleavage Lines

Skin Color

Factors that determine skin color include pigments in the skin, blood circulating through the skin, and the thickness of the stratum corneum. Melanin (mel′ă-nin; black) is the group of pigments primarily responsible for skin, hair, and eye color. Most melanin molecules are brown to black pigments, but some are yellowish or reddish. Melanin provides protection against ultraviolet light from the sun.

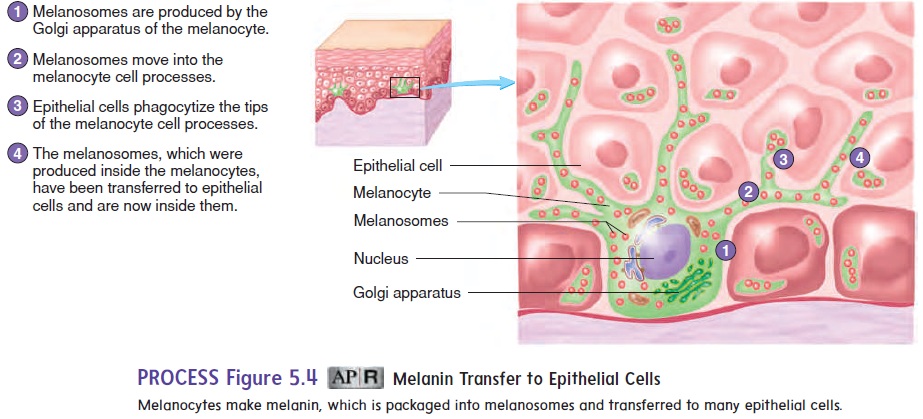

Melanin is produced by melanocytes (mel′ă-nō-sı̄tz; melano, black + kytos, cell), which are irregularly shaped cells with many long processes that extend between the epithelial cells of the deep part of the epidermis (figure 5.4). The Golgi apparatuses of the melanocytes package melanin into vesicles called melanosomes (mel′ă-nō-sōmz), which move into the cell processes of the mela- nocytes. Epithelial cells phagocytize the tips of the melanocyte cell processes, thereby acquiring melanosomes. Although all the epithelial cells of the epidermis can contain melanin, only the melanocytes produce it.

Large amounts of melanin form freckles or moles in some regions of the skin, as well as darkened areas in the genitalia, the nipples, and the circular areas around the nipples. Other areas, such as the lips, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet, contain less melanin.

Melanin production is determined by genetic factors, expo- sure to light, and hormones. Genetic factors are responsible for the amounts of melanin produced in different races. Since all races have about the same number of melanocytes, racial variations in skin color are determined by the amount, kind, and distribution of melanin. Although many genes are responsible for skin color, a single mutation can prevent the production of melanin. For exam- ple, albinism (al′bi-nizm) is a recessive genetic trait that causes a deficiency or an absence of melanin. Albinos have fair skin, white hair, and unpigmented irises in the eyes.

Exposure to ultraviolet light—for example, in sunlight— stimulates melanocytes to increase melanin production. The result is a suntan.

PROCESS Figure 5.4Melanin Transfer to Epithelial Cells

Certain hormones, such as estrogen and melanocyte-stimulating hormone, cause an increase in melanin production during pregnancy in the mother, darkening the nipples, the pigmented circular areas around the nipples, and the genitalia even more. The cheekbones and forehead can also darken, resulting in “the mask of pregnancy.” Also, a dark line of pigmentation can appear on the midline of the abdomen.

Blood flowing through the skin imparts a reddish hue, and when blood flow increases, the red color intensifies. Examples include blushing and the redness resulting from the inflammatory response. A decrease in blood flow, as occurs in shock, can make the skin appear pale. A decrease in the blood O2 content produces a bluish color of the skin, called cyanosis (s -ă -nō ′sis; dark blue). Birthmarks are congenital (present at birth) disorders of the blood vessels (capillaries) in the dermis.

Carotene (kar′̄o-t̄en) is a yellow pigment found in plantssuch as squash and carrots. Humans normally ingest carotene and use it as a source of vitamin A. Carotene is lipid-soluble; when consumed, it accumulates in the lipids of the stratum corneum and in the adipocytes of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. If large amounts of carotene are consumed, the skin can become quite yellowish.

The location of pigments and other substances in the skin affects the color produced. If a dark pigment is located in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue, light reflected off the dark pigment can be scattered by collagen fibers of the dermis to produce a blue color. The deeper within the dermis or subcutaneous tis-sue any dark pigment is located, the bluer the pigment appears because of the light-scattering effect of the overlying tissue. This effect causes the blue color of tattoos, bruises, and some super-ficial blood vessels.

Related Topics