Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Diagnosis of skin disorders

Side-room and office tests - Diagnosis of skin disorders

Side-room and office tests

A

number of tests can be performed in the practice office so that their results

will be available immediately.

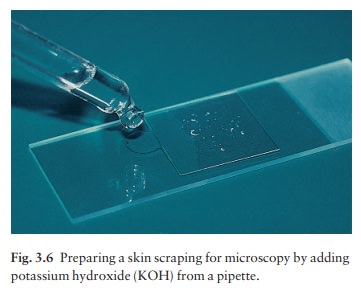

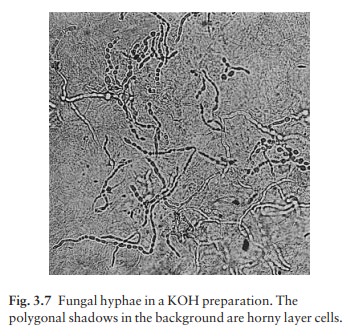

Potassium hydroxide preparations for fungal infections

If

a fungal infection is suspected, scales or plucked hairs can be dissolved in an

aqueous solution of 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH) containing 40% dimethyl

sulphoxide (DMSO). The scale from the edge of a scaling lesion is vigorously

scraped on to a glass slide with a No. 15 scalpel blade or the edge of a second

glass slide. Other samples can include nail clippings, the roofs of blisters,

hair pluckings, and the contents of pustules when a candidal infection is

suspected. A drop or two of the KOH solution is run under the cover slip (Fig.

3.6). After 5ŌĆō10 min the mount is examined under a microscope with the

condenser lens lowered to increase contrast. Nail clippings take longer to

clearaup to a couple of hours. With experience, fungal and candidal hyphae can

be readily detected (Fig. 3.7). No heat is required if DMSO is included in the

KOH solution.

Detection of a scabies mite

Burrows

in an itchy patient are diagnostic of scabies. Retrieving a mite from the skin

will confirm the diagnosis and convince a sceptical patient of the infestation.

The burrow should be examined under a magnifying glass; the acarus is seen as a

tiny black or grey dot at the most recent, least scaly end. It can

Alternatively, if mites are not seen, possible burrows can be vigorously

scraped with a No. 15 scalpel blade, moistened with liquid paraffin or

vegetable oil, and the scrapings transferred to a slide. Patients never argue

the toss when confronted by a magnified mobile mite. Dermatoscopy can also be used to detect the scabies mite.

Cytology (Tzanck smear)

Cytology

can aid diagnosis of viral infections such as herpes simplex and zoster, and of

bullous diseases such as pemphigus. A blister roof is removed and the cells

from the base of the blister are scraped off with a No. 10 or 15 surgical

blade. These cells are smeared on to a microscope slide, air-dried and fixed

with methanol. They are then stained with Giemsa, toluidine blue or WrightŌĆÖs

stain. Acantholytic cells are seen in

pemphigus and multinucleate giant cells are dia-gnostic of herpes simplex or

varicella zoster infec-tions . Practice is needed to get good preparations. The

technique remains popular in the USA but has fallen out of favour in the UK as

his-tology, virological culture and electron microscopy have become more

accessible.

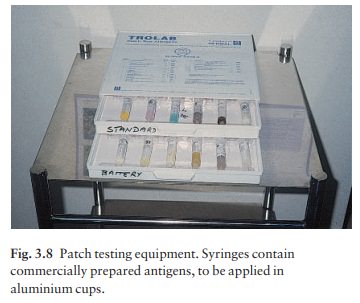

Patch tests

Patch

tests are invaluable in detecting the allergens responsible for allergic

contact dermatitis .

Either

suspected individual antigens, or a battery of antigens which are common

culprits, can be tested. Standard dilutions of the common antigens in

appro-priate bases are available commercially (Fig. 3.8). The test materials

are applied to the back under aluminium discs or patches; the occlusion

encourages penetration of the allergen. The patches are left in place for 48 h

and then, after careful marking, are removed. The sites are inspected 10 min

later, again at 96 h and some-times even later if doubtful reactions require

further assessment. The test detects type IV delayed hyper-sensitivity

reactions . The readings are scored according to the reaction seen. NT Not

tested.

0 No reaction.

┬▒ Doubtful

reaction (minimal erythema).

+ Weak

reaction (erythematous and maybe papular).

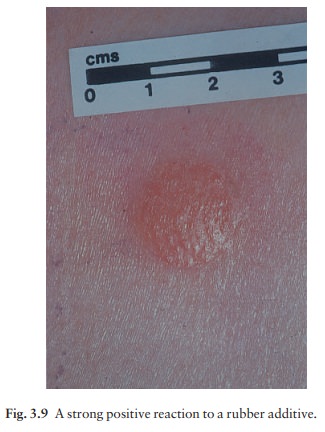

++ Strong

reaction (erythematous and oedematous or vesicular; Fig. 3.9).

++ + Extreme

reaction (erythematous and bullous). IR Irritant reaction (variable, but often

sharply cir-cumscribed, with a glazed appearance and increased skin markings).

A

positive patch test does not prove that the allergen in question has caused the

current episode of contact dermatitis; the results must be interpreted in the

light of the history and possible previous exposure to the allergen.

Patch

testing requires attention to detail in applying the patches properly, and

skill and experience in inter-preting the results.

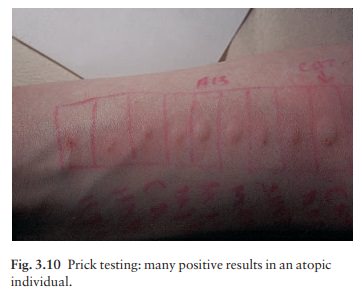

Prick testing

Prick

testing is much less helpful in dermatology. It detects immediate (type I)

hypersensitivity and patients should not

have taken systemic antihis-tamines for at least 48 h before the test.

Commercially prepared diluted antigens and a control are placed as single drops

on marked areas of the forearm. The skin is gently pricked through the drops

using separate sterile fine (e.g. Size 25 gauge, or smaller) needles. The prick

should not cause bleeding. The drops are then removed with a tissue wipe. After

10 min the sites are inspected and the diameter of any wheal measured and

recorded. A result is considered positive if the test antigen causes a wheal of

4 mm or greater (Fig. 3.10) and the control elicits negligible reaction. Like

patch testing, prick testing should not be undertaken by those without formal

training in the procedure. Although the risk of anaphylaxis is small,

resuscitation facilities including adrenaline (epinephrine) and oxygen must be available. The relevance of positive

results to the cause of the condition under investigationausually urticaria or

atopic dermatitisais often debatable. Positive results should correlate with

positive radio-allergosorbent tests (RAST;) used to measure total and specific

immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels to

Skin biopsy

Biopsy

(from the Greek bios

meaning ŌĆślifeŌĆÖ and opsis ŌĆśsightŌĆÖ) of skin lesions is useful

to establish or con-firm a clinical diagnosis. A piece of tissue is removed

surgically for histological examination and, sometimes, for other tests (e.g.

culture for organisms). When used selectively, a skin biopsy can solve the most

perplexing problem but, conversely, will be unhelpful in con-ditions without a

specific histology (e.g. most drug eruptions, pityriasis rosea, reactive

erythemas).

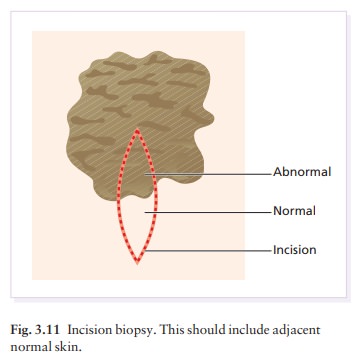

Skin

biopsies may be incisional,

when just part of a lesion is removed for laboratory examination or excisional,

when the whole lesion is cut out. Exci-sional biopsy is preferable for most

small lesions (up to 0.5 cm diameter) but incisional biopsy is chosen when the

partial removal of a larger lesion is adequate for diagnosis, and complete

removal might leave an unnecessary and unsightly scar. Ideally, an incisional

biopsy should include a piece of the surrounding normal skin (Fig. 3.11)

although this may not be possible if a small punch is used.

The

main steps in skin biopsy are:

administration of local anaesthesia;

and

removal of all (excision) or part

(incision) of the lesion and repair of the defect made by a scalpel or punch.

Local anaesthetic

Lignocaine

(lidocaine) 1ŌĆō2% is used. Sometimes adrena-line 1 : 200 000 is added. This

causes vasoconstriction, reduced clearance of the local anaesthetic and

pro-longation of the local anaesthetic effect. Plain lignocaine should be used

on the fingers, toes and penis as the prolonged vasoconstriction produced by

adrenaline can be dangerous here. Adrenaline is also best avoided in diabetics

with small vessel disease, in those with a history of heart disease (including

dysrhythmias), in patients taking non-selective ╬▒

blockers and tricyclic antidepressants (because of potential interactions) and

in uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. There are exceptions to these general rules

and, undoubtedly, the total dose of local anaesthetic and/or adrenaline is

important. Nevertheless, the rules should not be broken unless the surgeon is

quite sure that the procedure that he or she is about to embark on is safe.

It

is wise to avoid local anaesthesia during early pregnancy and to delay

non-urgent procedures until after the first trimester.

As

ŌĆśBŌĆÖ follows ŌĆśAŌĆÖ in the alphabet, get into the habit of checking the precise

concentration of the lignocaine added adrenaline on the label before

withdrawing it into the syringe and then, before injecting

it, confirm that the patient has not had any previous allergic reac-tions to

local anaesthetic.

Infiltration

of the local anaesthetic into the skin around the area to be biopsied is the

most widely used method. If the local anaesthetic is injected into the

subcutaneous fat, it will be relatively pain-free, will produce a diffuse

swelling of the skin and will take several minutes to induce anaesthesia.

Intradermal injections are painful and produce a discrete wheal associated with

rapid anaesthesia. The application of EMLA cream (eutectic mixture of local

anaesthesia) to the operation site 2 h before giving a local anaesthetic to

children helps to numb the initial prick.

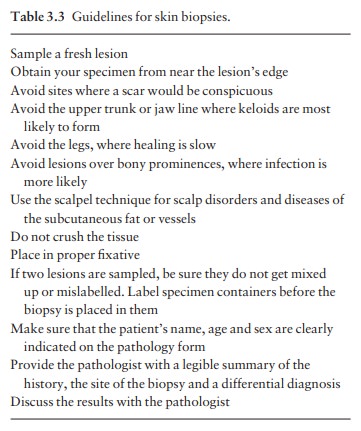

Scalpel biopsy

This

provides more tissue than a punch biopsy. It can be used routinely, but is

especially useful for biopsy-ing disorders of the subcutaneous fat, for

obtaining specimens with both normal and abnormal skin for comparison (Fig.

3.11) and for removing small lesions in toto (excision biopsy,). After selecting

thelesion for biopsy, an elliptical piece of skin is excised.

The

specimen should include the subcutaneous fat. Removing the specimen with

forceps may cause crush artefact, which can be avoided by lifting the specimen

with either a Gillies hook or a syringe needle. The wound is then sutured; firm

compression for 5 min stops oozing. Non-absorbable 3/0 sutures are used for

biopsies on the legs and back, 5/0 for the face, and 4/0 for elsewhere.

Stitches are usually removed from the face in 4 days, from the anterior trunk

and arms in 7 days, and from the back and legs in 10 days. Some guidelines for

skin biopsies are listed in Table 3.3.

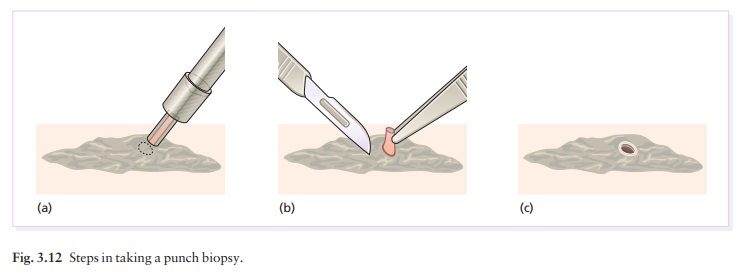

Punch biopsy

The

skin is sampled with a small (3 ŌĆō 4 mm diameter) tissue punch. Lignocaine 1% is

injected intradermally

Skin is lifted up carefully with a needle or forceps and the base

is cut off at the level of subcutaneous fat. The defect is cauterized or

repaired with a single suture. The biopsy specimen must not be crushed with the

forceps or critical histological patterns may be distorted.

The

tissue can be sent to the pathologist with a summary of the history, a

differential diagnosis and the patientŌĆÖs age. Close liaison with the

pathologist is essential, because the diagnosis may only become apparent with

knowledge of both the clinical and his-tological features.

Related Topics