Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Sexual Disorders

Sexual Disorders: The Sexual Dysfunctions

The Sexual Dysfunctions

Significance of Sexual Dysfunction

While sex is widely thought of as recreation, psychiatrists rec-ognize

it as an important means of establishing and reaffirming emotional attachments.

Sexual competence – the ability to desire a partner, become aroused and attain

orgasm in a cooperative manner when together – is a valuable developmental

accom-plishment because it enables a person to experience the physical

expressions and emotional complexities of love. Mutually pleas-urable sexual

behavior tends to recur far more often in couples than unilaterally satisfying

behavior. Mutually pleasurable sex-ual behavior allows both partners to be

comforted and stabilized by loving and feeling loved. The dysfunctions are

symptomatic deficits in the quest for these widespread ideals: sexual compe-tence,

fun and stabilization of the self.

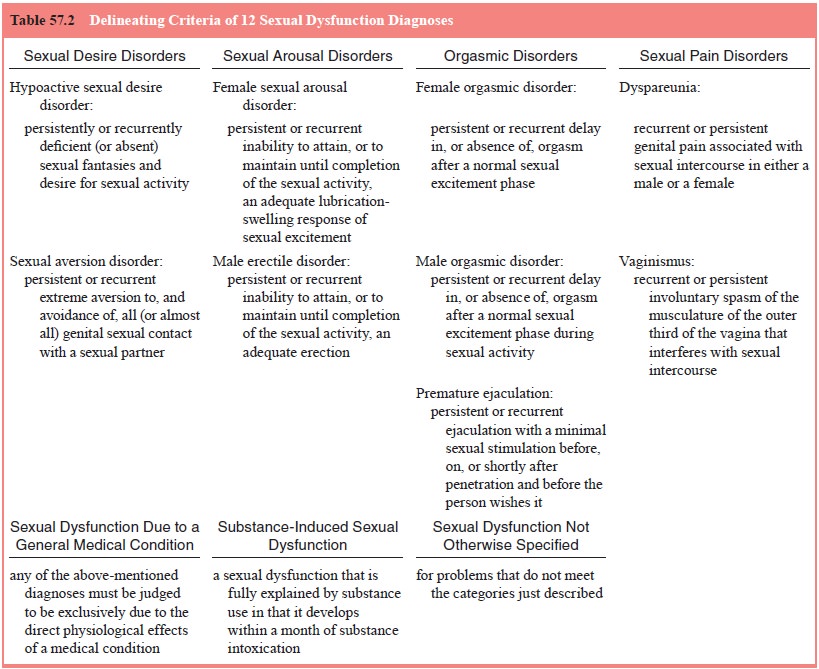

DSM-IV Diagnoses

DSM-IV specifies three criteria for each sexual dysfunction (American

Psychiatric Association, 1994). The first criterion describes the

psychophysiologic impairment – for example, ab-sence of sexual desire, arousal,

or orgasm. The second and third criteria are the same for each impairment: the

dysfunction causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty and the

dysfunction is not better accounted for by another Axis I diagnosis or not due

exclusively to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of

abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition. Table 57.2 lists the first

criterion of each of the 12 sexual dysfunc-tion diagnoses. DSM-IV gives the

clinician additional latitude

for deciding when a person who meets the first criterion qualifies for a

disorder. The doctor is asked to consider the effects of the individual’s age,

experience, ethnicity and cultural background, the degree of subjective

distress, adequacy of sexual stimulation and symptom frequency. No instructions

are provided about how to exercise this judgment. In this way DSM-IV makes it

clear that understanding sexual life requires more than counting symptoms; it

requires judgment.

Epidemiology

Numerous attempts to describe the prevalence of sexual dys-function have

been made in the previous 25 years. These range from attempts to define the

frequency of a particular dysfunc-tion, for instance male erectile disorder, to

attempts to esti-mate the prevalence of a series of separate dysfunction, for

example, desire, arousal and orgasmic disorders of women. All such efforts

quickly confront methodological influences of sampling, means of obtaining the

information, definition of each dysfunction, purpose of the study and

perspective of its authors. These data not surprisingly, therefore, demonstrate

a range of prevalence depending on the problem studied. Gender identity

disorders are relatively rare (,1–2%).

Lifelong sexual desire disorders among women may involve 15% but are less

frequent among men. Acquired desire disorders among older individuals are

probably three times as common. Perhaps more than half of women at age 55 years

have recognized a deterio-ration in their sexual function. Perhaps 25% of women

in their twenties have difficulty having orgasm and 33% of men less than age 40

claim to ejaculate too rapidly. The majority of men by age 70 years are likely

to be having erection problems. The recent careful epidemiologic study,

designed by sociologists, successfully generated a representative sample of the

USA (Laumann et al., 1994a). They

interviewed men and women between age 18 and 59 years and found that sexual

dysfunc-tion is common, particularly among young women and older men. This is

noteworthy for psychiatrists because our stud-ies of sexual dysfunction caused

by medications or acquired psychiatric disorders tend to assume that patients

are gener-ally functionally intact prior to becoming ill or taking

medica-tions. This assumption is not tenable based on a generation of

epidemiologic studies.

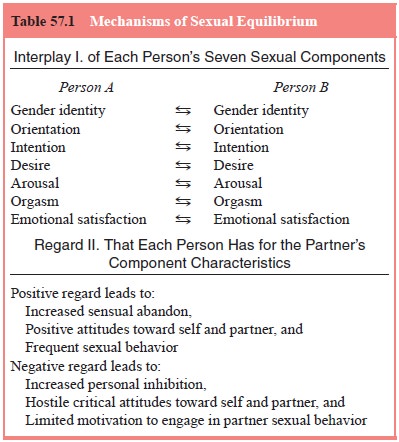

Sexual Equilibrium

Etiologic ideas about sexual dysfunction are a relatively simple

conceptual challenge involving notions about the individual’s psychology and

his or her cultural expectations. In contrast, for couples, they involve two

individual psychologies, their interpersonal impact on one another and their

cultures. The cli-nician must be wary when one coupled person is presented as

having a sexual dysfunction and the partner is presented as “nor-mal”. Sexual

dysfunction in a couple is a two-person problem in terms of immediate effects

and often in terms of cause as well (Table 57.1). How a partner regards the

sexual characteristics of the other is a subtle ingredient of sexual comfort,

competence and dysfunction. For instance, a young woman’s new inability to

attain orgasm with her husband may be traced to her embarrass-ment at sharing

her excitation with him because she perceives him to be generally critical of

her. Similarly, the origin of a hus-band’s erectile dysfunction may be traced

to the emergence of his wife’s negative regard for him, which stemmed from

something other than his sexual behavior. This ordinary connectivity of a couple’s sexual function is referred to

as the couple’s sexual equilibrium (Levine, 1998). The sexual equilibrium

explains five observations:

·

Improvement and deterioration of

sexual function can rapidly occur;

·

When a couple’s nonsexual

relationship is good, their sexual life may not be;

·

Individual psychotherapy is often

insufficient to help coupled patients improve their sexual life;

·

A negative attitude from the

partner can block improvement in a couple’s sexual life regardless of the

therapy format and therapist skill;

·

A conversation with a therapist

who is attuned to the emotional meanings of a couple’s interaction can shift a

dysfunctional equilibrium back to mutually satisfying sexual behavior

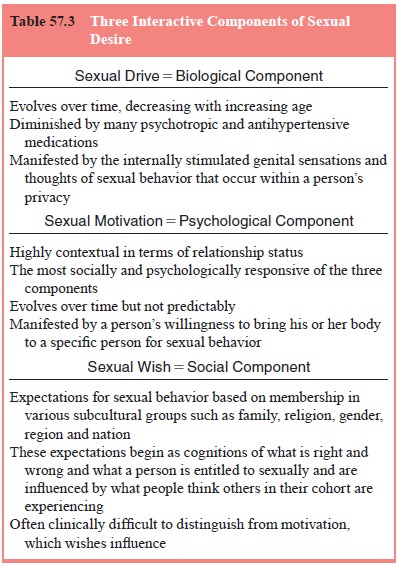

The Problems of Sexual Desire

Sexual desire manifestations are diverse: erotic fantasies, sexual

dreams, initiation of sexual behavior, receptivity to partner-initiated sexual

behavior, masturbation, genital sensa-tions, heightened responsivity to erotic

environmental cues and sincere statements about wanting to behave sexually. For

most of the 20th century, these have been referred to as manifestations of

libido. Psychiatrists spoke of libido as if it was a homogeneous instinctive

force. Clinicians will find it far more useful to concep-tualize that the

diverse and changeable desire manifestations are produced by the intersection

of three mental forces: drive (biol-ogy), motive (psychology) and wish

(culture).

Drive

By only partially understood psychoneuroendocrine mecha-nisms, the preoptic

area of the anterior-medial hypothalamus and the limbic system periodically

produce sexual drive. Drive is

recognized by genital tingling, heightened responsivity to erotic environmental

cues, plans for self or partner sexual behavior, nocturnal orgasm and increased

erotic preoccupations. These are often spontaneous. Although people can become

aroused and at-tain orgasm without evident drive, it propels the entire sexual

psychophysiological process. Without drive, the sexual response system is far less

efficient and capable. While men as a group seem to have significant more drive

than women as a group, in both sexes, drive requires the presence of a modest

amount of testosterone. Drive is frequently dampened by medications that act

within the central nervous system, substances of abuse, psy-chiatric illness,

systemic physical illness, despair and aging. It is heightened by low doses of

a few often-abused substances such as alcohol or amphetamine, manic mechanisms,

falling in love, joy, and some dopaminergic compounds such as those used to

treat Parkinson’s disease.

Motive

The psychological aspect of desire is referred to as motive and is recognized by willingness

to bring one’s body to the part-ner for sexual behavior either through

initiation or receptivity. Motive often directly stems from the person’s

perception of the context of the nonsexual and sexual relationship. Sexual

desire diagnoses are often made in persons who have adequate drive

manifestations. Most sexual desire problems in physically healthy adults are

simply generated by one partner’s unwill-ingness to engage in sexual behavior.

This is often a secret, however. Sexual motives are originally programmed by

social and cultural experiences. Children and adolescents acquire values, beliefs,

expectations and rules for sexual expression. Young people have to find a way

to negotiate their way through the fact that their early motives to behave

sexually frequently coexist with their motives not to engage in sexual behavior. Conflicted motives often persist

throughout life but the reasons for the conflict evolve. A teenager possessed

of considerable drive and motive to make love may inhibit all sexual

activi-ties because of moral considerations emanating from religious education

or the sense that he or she is just not developmentally ready yet.

Wish

An 80-year-old man who had no drive manifestations and had avoided all

sexual contact with his wife for a decade because he could not get an erection,

passionately answered a doctor’s query about his sexual desire, “Of course, I

have sexual desire! I am a red-blooded American male! Why do you think I am

here?” In fact, he was only speaking about his wish to be sexually capable now

that an effective treatment for erectile problems existed. The doctor asked an

imprecise question. The doctor should have sepa-rately explored his drive

manifestations, his sexual motivation to exchange sexual pleasure with his wife

in recent years and his wish for sexual rejuvenation.

The appearance and disappearance of sexual desire is of-ten enigmatic to

a patient, but its ebb and flow result from the ever-changing intensities of

its components, biological drive,

psychological motive and socially

acquired concepts, wish (Table 57.3)

(Levine, 2002). In women, this interplay is generally more difficult to

delineate because drive and motive are some-times inseparable.

Sexual Desire Diagnoses

Two official diagnoses are given to men and women whose desires for partner sexual behavior are deficient: hypoactive sex-ual desire disorder (HSDD) and sexual aversion disorder (SAD). The differences between the two revolve around the emotional intensity with which the patient avoids sexual behavior. When visceral anxiety, fear, or disgust is routinely felt as sexual behav-ior becomes a possibility, sexual aversion is diagnosed. HSDD is far more frequently encountered. It is present in at least twice as many women than men; female to male ratio for aversion is far higher. Like all sexual dysfunctions, the desire diagnoses may be lifelong or may have been acquired after a period of ordinary fluctuations of sexual desire. Acquired disorders may be partner specific (“situational”) or may occur with all subsequent partners (“generalized”).

When the psychiatrist concludes that the patient’s acquired generalized

HSDD is either due to a medical condition, a medica-tion, or a substance of

abuse, the diagnosis is further elaborated to sexual dysfunction due to general

medical condition (for in-stance, HSDD due to multiple sclerosis). The

frequency of the specific etiologies are heavily dependent on the clinical

setting. In oncology settings, medical causes occur in high frequency; in drug

rehabilitation programs, methadone maintenance will be a common cause. In

marital therapy clinics, anger and loss of respect for the partner, hidden

incompatibility of sexual identity between the self and the partner because of

covert homosexuality or paraphilia, an affair, or childhood sexual abuse will

commonly be the basis. In general psychiatry settings, medication side ef-fects

will often be the top layer of several causes. When a major depression disorder

is diagnosed, for instance, the desire disorder is often assumed to be a

symptom of the depression. This usually is incorrect. The desire disorder often

preceded the decompensa-tion into depression.

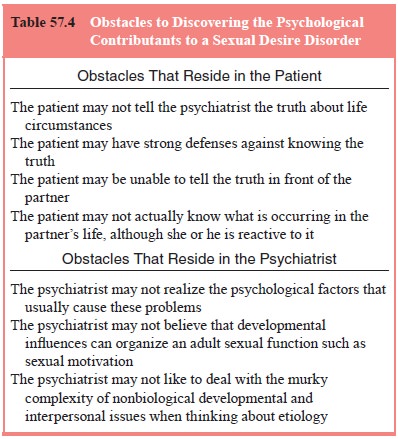

From a Desire Diagnosis to Dynamics

Those with lifelong

deficiencies of sexual desire are often per-ceived to be struggling with

either: 1) sexual identity issues in-volving gender identity, orientation, or a

paraphilia; 2) having failed to grow comfortable as a sexual person due to

extremely conservative cultural backgrounds, developmental misfortunes, or

abuses. Occasionally the etiology is enigmatic, raising the im-portant question

whether it is possible to never have any sexual drive manifestations on a

biological basis. (Theoretically, the answer is yes.) Both acquired and

lifelong desire disorders are often associated with past or chronic mood

disorders. Disorders of desire are often listed as “of unknown etiology”, but

clinicians should be skeptical of this idea because:

·

The patient may not tell the doctor

the truth early in the relationship;

·

The patient may have strong

defenses against knowing the truth;

·

The patient may not be able to

speak freely in front of the partner;

·

The patient may not know what is

occurring in the partner’s life, despite being influenced negatively by it;

·

The doctor may not realize the

usual causes of the problem;

·

The doctor may not believe in

developmental influences on the organization of adult sexual function.

Sexual aversion should strongly suggest three possibilities to the

clinician:

·

that a remote traumatic

experience is being relived by the partner’s expression of interest in sexual

behavior;

·

that without the symptom the

patient feels powerless to say “no” to sexual advances;

·

the patient feels guilty about

her own sexual behavior with another person.

The doctor’s attention should focus on the patient’s sexual devel-opment

as a child, adolescent and young adult when the aversion is lifelong, whereas

when it is acquired, the focus of

the his-tory should be on the period immediately prior to the onset of the

symptom.

Desire disorders require the clinician to think both in terms of

development and personal meanings of sex to their indi-vidual patients (Table

57.4). Because all explanations are specu-lative, they should at least make

compelling sense of the patients’ life experiences. Some explanations are based

on the influence

of remote developmental processes. The term madonna–whore complex misleads

us into thinking this is only a male pattern. The syndrome is manifested by normal sexual capacity with anyone

but the fiancé or spouse. Freud interpreted this as a sign of incomplete

resolution of the oedipal complex. The man was thought to be unable sexually to

desire his beloved because he had unconsciously made her into his mother. He

withdrew his sexual interest from her to protect himself from symbolic incest.

Some women are comparably unable sexually to enjoy their part-ners because they

unconsciously confuse their beloved with their father. Another form can be seen

among patients whose parents were grossly inadequate caregivers. When these men

and women find a reliable, kind, supportive person to marry, they quickly

discover a strong motive to avoid sexual behavior with their fiancé. The

patient makes the partner into a good-enough parent, experiences anxiety as an

unconscious threat of incest associ-ated with the possibility of sex, and

becomes skillful at avoiding sexual opportunities.

Most sexual desire disorders are difficult to overcome quickly. Brief

treatment generally should not be undertaken. Serious individual or couple

issues frequently underlie these diagnoses. They have to be afforded time to

emerge and to be worked through. However, clinicians need not be pessimistic

about all of these conditions. For example, helping a couple re-solve a marital

dispute may return them to their usual normal sexual desire manifestations. For

many individuals and couples, therapy assists the couple to accept more calmly

the profound implications of continuing marital discord, infidelity,

homosexu-ality, or other contributing factors. Some treatment failures lead to

divorce and the creation of a relationship with a new partner. There is then no

further sign of the desire problem. Problems rooted in early developmental

experiences are particularly diffi-cult to overcome. While DSM-IV asks the

clinician to make many distinctions among the desire disorders, no follow-up

study has been published in which either the subtypes (lifelong, acquired,

situational, generalized) or etiologic organizers (relationship de-terioration

with and without extramarital affairs, sexual identity incompatibilities,

parental, and medical) are separated into good and poor prognosis categories.

Developmental and identity matters are typically approached in long-term

individual psychotherapy. In these ses-sions women often discuss the

development of their femininity from adolescence to young womanhood, focusing

on issues of body image, beauty, social worth to others, moral sensibilities, social

awkwardness and whether they consider themselves de-serving of personal

physical pleasure. Men often discuss similar issues in terms of masculinity.

Anger, loss of respect, marital discord and extramarital af-fairs may be

approached in either individual or conjoint formats. In either setting,

patients often formulate the etiology as having fallen out of love with the

partner. Those whose cultural back-grounds limit their ease in being a sexual

person are often en-couraged in educational and cultural experiences that might

help them outgrow their earliest notions about what is proper sexual behavior.

The Problems of Sexual Arousal

The emotion interchangeably referred to as sexual arousal or sexual

excitement generates changes in respiration, pulse and muscular tension as well

as an increased blood flow to the geni-tals. Genital vasocongestion creates

vaginal lubrication, clitoral tumescence, labial color changes, and penile

erection, testicu lar elevation and penile color changes. How arousal is centrally

coordinated in either sex remains mysterious. During lovemak-ing, men and women

do not necessarily maintain or progressively increase their arousal; rather

often there is a fluctuating intensity of arousal which is reflected in

variations in vaginal wetness and penile turgidity and nongenital signs of

arousal.

Female Sexual Arousal Disorder

The specificity and validity of this disorder is unclear. In women it is

far more difficult to separate arousal and desire problems than in men. The

perimenopausal period is now recognized as generating complaints about

decreased drive, motivation, lubri-cation and arousal in at least 35 to 50% of

women. However, it is unclear whether to label the problem as primarily of

desire or arousal. It is assumed to be endocrine in origin even though

estrogen, progesterone and testosterone replacement do not reli-ably reverse

the pattern. Even in younger regularly menstruating women, however, diminished

motivation and dampened drive makes it difficult to sustain arousal. Many have

called into ques-tion the accepted notions that desire necessarily precedes

arousal and that they are separate physiological processes. Female arousal

disorder implies that drive and motivation are relatively intact although

arousal is difficult. The disorder is usually an ac-quired diagnosis. Premenopausal women who have it focus on the lack of moisture in the vagina or

their failure to be excited by the behaviors that previously reliably brought

pleasure. They have drive and motive and wish, but enigmatically are unable to

sustain arousal. Some mental factor arises to distract them from their

excitement during lovemaking. Therapy is focused, therefore, on the meaning of

what preoccupies them. This often involves the dynamics of their current

individual or partnered life or the influence of their past relationships on

their present. With therapy the diagnosis often is changed to a HSDD.

In peri- and postmenopausal women, arousal problems are more often

focused on the body as a whole rather than just genital moisture deficiencies.

Skin insensitivity, often a euphemism for decreased pleasure in response to

oral and manual nipple, breast and vulvar stimulation, is often initially

treated as a symptom of “estrogen” deficiency. Early in the menopause, a small

minority of women have an increase in drive due to changing

testoster-one–estrogen ratios. Yet, they may still subjectively experience

arousal as different than it used to be. Therapy often focuses on the women’s

concerns about estrogen replacement and the con-sequences of menopause in terms

of body image, attractiveness, fears of partner infidelity, loss of health and

vigor, and aging.

Aging of the female arousal mechanisms, whether simply due to shifts in

ovarian endocrine production or systemic aging mechanisms, occurs earlier than

deterioration of orgasmic physi-ology. Women with decreasing arousal are often,

therefore, still reliably orgasmic with the use of vaginal lubricants well into

old age. Women who have been treated with chemotherapy for breast cancer are a

particularly problematic group to offer as-sistance to for their new arousal problems.

Fear of stimulating remaining cancerous cells makes systemic estrogen

replacement contraindicated.

In 1999 a

renewed interest in female arousal disorder, some-times casually called female

sexual dysfunction surfaced in response to the efficacy of Viagra for men’s

arousal problems. It was reasoned that since the penis and clitoris are

embryologic homologues with comparable adult histology, the drug would improve

women’s arousal. Placebo-controlled trials concluded that the drug did not

improve arousal any more than placebo (Basson et al., 2002).

Male Erectile Disorder

The mechanisms of erection – the sequestering and maintaining arterial

blood within the corpora cavernosa – are being elucidated by urological

research. Their research has led to a diminishing emphasis on “psychogenic

impotence” diagnosis. Urologists may refer to male erectile disorders (ED) of a

psychogenic origin as “adrenergic” ED, a reference to the preponderance of

sympa-thetic tone on the corporal mechanisms that maintain flaccidity.

Adrenergic dominance of the penile arterial tone is created by a mind that

perceives the sexual context as a dangerous, frighten-ing, or as unwanted.

The prevalence of ED rises dramatically in the sixth dec-ade of life

from less than 10 to 30%; it increases further during the seventh decade.

Aging, medical conditions such as diabe-tes, prostatic cancer, hypertension and

cardiovascular risk fac-tors predict the most common pattern of ED due to a

medical condition in this age group. While medication-induced, neuro-logical,

endocrine, metabolic, radiation and surgical causes of erectile dysfunction

also exist, in population studies diabetes, hypertension, smoking, lipid

abnormalities, obesity and lack of exercise are correlated with the progressive

deterioration of erec-tile functioning in the sixth and seventh decades. These

factors are thought to create a relative penile anoxemia which stimulates the

conversion of corporal smooth muscle cells into fibrocytes. The gradual loss of

elasticity of the corpora interferes with fill-ing and sequestering of arterial

blood. Erections at first become unreliable and finally impossible to obtain or

sustain.

At every age, selectivity of

erectile failure is the single most important diagnostic feature of primary

erectile dysfunc-tion. Clinicians should inquire about the relative firmness

and duration of erections under each of these circumstances: mas-turbation, sex

other than intercourse, sex with other female or male partners, upon

stimulation with explicit media materials, in the middle of the night and upon

awakening. If under some circumstances the erection is firm and lasting, the

clinician can usually assume that the man’s neural, endocrine and vascular

physiology is sufficiently normal and that the problem is psycho-genic in

origin. This is true even for men in their fifties and older. Clinicians often

feel more certain about this diagnosis when no diseases thought to lead to

erectile dysfunction are present.

Lifelong male ED typically is psychogenic and involves ei-ther a sexual

identity dilemma: such as transvestism, gender iden-tity disorder, a homoerotic

orientation, a paraphilia, or another diagnosis that expresses the patient’s

fear of being sexually close to a partner. Sexual identity problems are often initially

denied unless the clinician is nonjudgmental and thorough during the inquiry.

However, obsessive–compulsive disorder, schizoid per-sonality, a psychotic

disorder, or severe character disorders may be present. Occasionally, a

reasonably normal young man with an unusually persistent fear of sexual

intercourse seeks attention. These good prognosis cases are sometimes

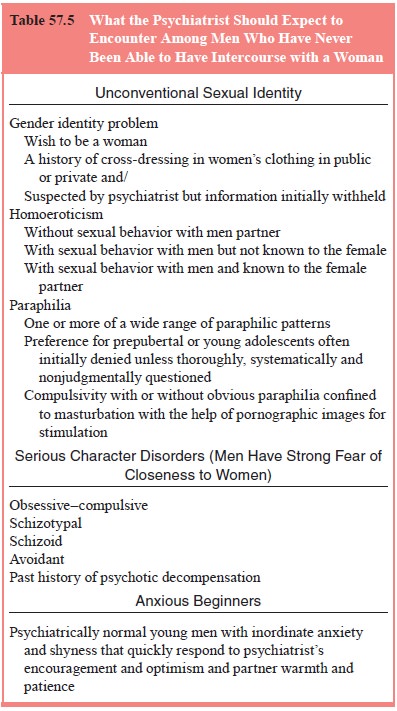

informally referred to as anxious beginners (Table 57.5). With that exception,

men with lifelong male arousal disorder (MAD), when taken into in-dividual

therapy are usually perceived as having a strong motive to avoid sexual

behavior and while dysfunctional with a partner during much of their therapy

might equally be diagnosed as hav-ing HSDD with normal drive but a motive to

avoid partner sex. The prognosis with older men with lifelong erectile

dysfunction is poor even with modern erectogenic agents. Long-term therapy,

even if it does not enable regular intercourse, may enable more emotional and

sexual closeness to a partner. Some reasonably masculine appearing men with

mild gender identity problems

can quickly become potent if they can reveal their need during sexual

relationship to cross-dress (use a fetish article of clothing) to a partner who

calmly accepts his requirement. However, most of these men have inordinate

fears of sexually bonding to any woman and, in therapy, become preoccupied with

basic devel-opmental issues. Some of them marry and form companionate

relationships that are rarely or never consummated.

In dramatic contrast, men with long-established good po-tency who have

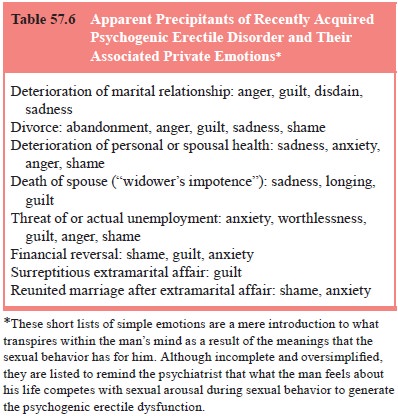

recently lost their erectile capacities with their partner – acquired

psychogenic ED – have a far better prognosis (Table 57.6). They may be treated

in individual or couples format, depending on the precipitants of the sexual

problem and the status of their relationship with their partner. Many of these

therapies become focused on resentments that have not been identified,

dis-cussed and worked through by the couple. Such distressed couples are most

efficiently helped in a conjoint format. When extramari-tal affairs are part of

the relationship deterioration and cannot be discussed, most clinicians simply

work with one spouse. Potency is frequently lost following a separation or

divorce. Impaired potency after a spouse’s death is either about unresolved

grief or problems that exist prior to the wife’s terminal illness. Men are also

often worried about their potency when their financial or

vocational lives crumble, when they have a serious new physical illness

such as a myocardial infarction or stroke, or when their wives become seriously

ill. The esthetics of lovemaking require a context of reasonable physical

health; when one spouse becomes chronically ill or disfigured by illness or

surgery, either one of the couple may lose their willingness to be sexual. This

may be reflected in impaired erections or sexual avoidance.

Regardless of the precipitating factors, men with arousal disorders have

performance anxiety. They anticipate erectile failure before sex begins and

vigilantly monitor their state of tumescence during sex (Masters and Johnson,

1970). Perform-ance anxiety is present in almost all impotent men. Performance

anxiety is efficiently therapeutically addressed by identifying it to the

patient and asking him to make love without trying inter-course on several

occasions to demonstrate to himself how dif-ferent lovemaking can feel for him

when he is not risking failure. This enables many to relax, concentrate on

sensation and return to previous states of sensual abandon during lovemaking.

This technique is known as sensate focus.

The psychological treatment of acquired arousal disorders is often

highly satisfying for the professional because many of the men are anxious for

help. Motivation to behave sexually is often present, fear can be allayed and

men can learn to appreci-ate the emotional complexity of their lives. They can

be shown how their minds prevented intercourse until they could acknowl-edge

what has been transpiring within and around them. Many recently separated men,

for example, are grieving, angry, guilty, uncertain and worried about their

finances. Yet, they may pro-pel themselves into a new relationship. Two

characteristics seem to predispose to erectile problems at key life

transitions: 1) The pursuit of the masculine standard that men ought to be able

to perform intercourse with anyone, anywhere, under any circum-stances; 2) The

inability to readily grasp the nature and signifi-cance of his inner

experiences. “Yes, my schizophrenic daughter became homeless in another city,

my wife was depressed and be-gan drinking to excess in response, and I had a financially

costly affair with my secretary. What do these have to do with my loss of

potency?” (Table 57.7).

Sildenafil revolutionized the treatment of erectile dysfunc-tion in

1998. This phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor maintains corporal vasodilatation

by preventing the degradation of cGMP. Sexual arousal leads to the corporal

secretion of nitric oxide which is converted by an enzyme into cGMP. Sildenafil

is in-creasingly effective as the dose is increased from 25 to 50 up to 100 mg.

The drug must not be used when any organic nitrate is being taken because it

dangerously potentiates the hypoten-sive effect of the nitrates risking brain

and myocardial infarction. Sildenafil is dramatically underutilized by

psychiatrists.

Prior to sildenafil, urologists argued that most erectile dys-function

was organic in origin, but since the drug works at about the same rate

regardless of the pretreatment etiology, most erec-tile dysfunction is now

recognized to be of mixed – organic and psychosocial – origin. Three conditions

have unique response profiles: after prostatectomy the response rate is

approximately 34%, among diabetics it is approximately 43%, and among the

spinal cord injured it is approximately 80%; the same rate seems to improve

psychogenic ED. Other medical interventions are also effective in varying

degrees for largely organic erectile dysfunc-tion: vacuum pump, the

intracavernosal injection of vasodilating substances, intraurethral aprostadil,

the surgical implantation of a penile prostheses and, outside the USA,

sublingual apomor-phine. Because sildenafil’s rate of improving erections is

sig-nificantly higher than the restoration of a mutually satisfactory sexual

equilibrium (approximately 44%), psychological ED that persists after medication

should be treated by a mental health professional.

Related Topics