Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Sexual Disorders

Sexual Disorders: Gender Identity Disorders

Gender Identity Disorders

The

organization of a stable gender identity is the first component of sexual

identity to emerge during childhood. The processes that enable this

accomplishment are so subtle that when a daughter consistently acts as though

she realizes that “I am a girl and that is all right”, or when a son’s behavior

announces that “I am a boy and that is all right”, families rarely even

remember their chil-dren’s confusion and behaviors to the contrary. Adolescent

and adult gender problems are not rare. They are however commonly hidden from

social view, sometimes long enough to developmen-tally evolve into other less

dramatic forms of sexual identity

Early Forms

Extremely Feminine Young Boys

Although occasionally the parents of a feminine son have a con-vincing

anecdote about persistent feminine interests dating from early in the second

year of life, boyhood femininity is more typi-cally only apparent by the third

year. By the fourth year playmate preferences become obvious. Same-sex playmate

preference is a typical characteristic of young children.

Cross-gender–identified children consistently demonstrate the opposite sex

playmate pref-erence. The avoidance of other boys has serious consequences in

terms of social rejection and loneliness throughout the school years. The peer

problems of feminine boys cause some of their behavioral and emotional problems

which are in evidence by mid-dle-to-late childhood. However, psychometric

studies support clinical impressions that feminine boys have emotional problems

even before peer relationships become a factor, that is, something more basic

about being cross-gender-identified creates problems. Young feminine boys have

been shown to be depressed and have difficulties with separation anxiety.

Speculations about the origin of boyhood femininity generally suggest

converging cumulative forces. Any child’s cross-gender identifications are

likely to involve a host of fac-tors: constitutional forces, problematic

interactions with parents, problematic internal processing of life experiences

and family misfortune: financial, reproductive, physical disease, emotional

illness, or death of vital persons. These factors are sometimes restated as

temperament, disturbed family functioning, separa-tion–individuation problems

and trauma.

Temperament is a dual phenomenon being both the child’s predisposition

to respond to the world in a certain way and the as-pects of the child to which

others respond. The common tempera-mental factors of feminine boys have been

described as: a sense of body fragility and vulnerability that leads to the

avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; timidity and fearfulness in the face of new

situations; a vulnerability to separation and loss; an unusual capacity for

positive emotional connection to others; an ability to imitate; sensitivities

to sound, color, texture, odor, temperature and pain (Coates et al., 1992).

The development of boyhood femininity may occur within the mind of the

toddler in response to a loss of emotional avail-ability of the nurturant

mother. The child creates a maternal (feminine) self through imitation and

fantasy in order to make up for the mother’s emotional unavailability. This

occurs beyond the family’s awareness and is left in place by the family either

ignoring what has transpired in the son or valuing it. The problem for the

effeminate boy is that reality – the social expectations of other people – is

unyielding on gender issues; the adaptive early life solution becomes

progressively more maladaptive with time.

The answer to the question whether boyhood femininity is entirely

constitutional, an adaptive solution, or due to a combina-tion that includes

some other process is not known. A few reports of femininity giving way to

psychotherapeutic interventions with young boys and their families are of

heuristic value but limited in follow-up duration.

Green prospectively studied a large well-matched group of feminine boys

for over a decade and discovered that boyhood ef-feminacy was a frequent

precursor of adolescent homoeroticism and homosexual behavior rather than

gender identity disorders. He observed, as had others before, that without

therapy feminine gender role behaviors give rise to more masculine behavioral

styles as adolescence emerges (Green, 1987).

Masculine Girls: Tomboys

The masculinity of girls may become apparent as early as age 2 years.

The number of girls brought to clinical attention for cross-gendered behaviors,

self-statements and aspirations is con-sistently less than boys by a factor of

1: 5 at any age of childhood in Western countries (except Poland). It is not

known whether this reflects a genuine difference in incidence of childhood

gen-der disorders, cultural perceptions of femininity as a negative in boys

versus the neutral-to-positive perception of boy-like behav-iors in girls, the

broader range of cross-gender expression per-mitted to girls but not to boys,

or an intuitive understanding that cross-gender identity more accurately

predicts homosexuality in boys than girls.

The distinction between tomboys and gender-disordered girls is often

difficult to make. Tomboys are thought of as not as deeply unhappy about their

femaleness, not as impossible occa-sionally to dress in stereotypic female

clothing, and not thought to have a profound aversion to their girlish and

future womanly physiologic transformations. Tomboys are able to enjoy some

fem-inine activities along with their obvious pleasures in masculine-identified

toys and games and the company of boys. Girls who are diagnosed as gender-disordered

generally seem to have a relentless intensity about their masculine

preoccupations and an insistence about their future. The onset of their

cross-gendered identifications is early in life. Although most lesbians have a

history of tomboyish behaviors, most tomboys develop a heterosexual

orientation.

The Subjectivity of a Well-developed Gender Disorder

Children, teenagers and adults exist who rue the day they were born to

their biological sex and who long for the opportunity sim-ply to live their

lives in a manner befitting the other gender. They repudiate the possibility of

finding happiness within the broad framework of roles given to members of their

sex by their society. Their repudiation is not motivated by an intellectual

attack on sexism, homophobia, or any other injustice imbedded in cultural

mores. A gender-disordered person literally repudiates his or her body,

repudiates the self in that body and rejects performing roles expected of

people with that body. It is a subtle, usually self-contained rebellion against

the need of others to designate them in terms of their biological sex.

The repudiation and rebellion may first occur as a subjec-tive internal

drama of fantasy, as behavioral expression in play, or a preference for the company

of others. Regardless of when and how it is displayed, the drama of the

gender-disordered involves the relentless feeling that “life would be better –

easier, fuller, more enjoyable – if I and others could experience me as a

mem-ber of the opposite sex”.

By mid-adolescence, the extremely gender-disordered have often

envisioned the solution for their paralyzing self-consciousness: to live as a

member of the opposite gender, to transform their bodies to the extent possible

by modern medicine, and to be accepted by all others as the opposite sex. Most

people with these cross-gender preoccupations, however, do not go be-yond the

fantasy or private cross-dressing. Those that do eventu-ally come to

psychiatric attention. When a clinician is called in, the family has one set of

hopes, the patient another. The clinician has many tasks, one of which is to

mediate between the ambitions of the gender-disordered person and society and

see what can be done to help the patient. Negative countertransference may steer

the clinician to deal with the opportunity expeditiously: “Obvi-ously the

patient is sick, maybe psychotic, and needs help. I don’t take care of people

who do these things. Refer it out!” With a lit-tle supervisory encouragement to

perform a thorough evaluation, therapists soon find that these patients possess

many of the ordi-nary aspects of life and one unusual ambition: they often want

to be the opposite sex so badly that they are willing to make it a priority

over family, friends, vocation and material acquisition.

Diagnostic Criteria of Gender Identity Disorder

Adults who permanently change their bodies to deal with their gender

dilemmas represent the far end of the spectrum of adapta-tions to gender

problems. Even the lives of those who reject bod-ily change, however, have

considerable pain because the images of a better gendered self may recur

throughout life, becoming more powerful whenever life becomes strained or

disappointing.

The diagnosis of the extreme end of the gender identity dis-order spectrum

is clinically obvious. The challenging diagnostic task for clinicians is to

suspect a gender problem and inquire about gender identity and its evolution in

those whose manner suggest unisexed or cross-gendered appearance, those with

dissociative gender identity disorder (GID), severe forms of character

pathol-ogy and those who seem unusual in some undefinable manner.

DSM-IV provides the clinician with two Axis I gender diagnoses. To

qualify for the first, a patient of any age must meet four criteria:

Criterion 1: Strong, persistent

cross-gender identifica-tion Because

young children may not verbalize enough about their inner experiences for the clinician to be certain that this

criterion is met, at least four of five manifestations of cross-gen-der

identification must be present: 1) repeatedly stated desire to be, or

insistence that he or she is, the opposite sex; 2) in boys, preference for

cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls, insistence on wearing

stereotypical masculine clothing; 3) strong and persistent preferences for

cross-gender roles in fantasy play or persistent fantasies of being the

opposite sex; 4) intense de-sire to participate in the games and pastimes of

the opposite sex; 5) strong preference for playmates of the opposite sex.

In adolescence and adulthood, this criterion is fulfilled when the

patient states the desire to be the opposite sex, has fre-quent social forays

into appearing as the opposite sex, desires to live or be treated as the

opposite sex, or has the conviction that his or her feelings and reactions are

those typical of the opposite sex.

Criterion 2: Persistent

discomfort with one’s gender or the sense of inappropriateness in a gender role

This criterion is fulfilled in boys who assert that their penis or testicles are

dis-gusting or will disappear or that it would be better not to have these

organs; or who demonstrate an aversion toward rough-and-tumble play and

rejection of male stereotypical toys, games and activities. In girls, rejection

of urinating in a sitting position or assertion that they do not want to grow

breasts or menstruate, or marked aversion towards normative feminine clothing

fulfill this criterion.

Among adolescents and adults, this criterion is fulfilled by the

patients’ exhibiting the following characteristics: preoc-cupation with getting

rid of primary and secondary sex charac-teristics; preoccupation with thoughts

about hormones, surgery, or other alterations of the body to enhance the

capacity to pass as a member of the opposite sex such as electrolysis for beard

removal, cricoid cartilage shave to minimize the Adam’s apple, breast

augmentation, or preoccupation with the belief that one was born into the wrong

sex.

Criterion 3: Not due to an

intersex condition In the vast ma-jority of clinical

circumstances the patient possesses normal gen-ital anatomy and sexual

physiology. When a patient with a gender identity disorder and an accompanying

intersex condition such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, an anomaly of the

genitalia, or a chromosomal abnormality is encountered, the clinician will be

uncertain whether the intersex condition is the cause of the GID. The clinician

may either diagnose gender identity disorder not otherwise specified (GIDNOS)

or classify the patient as hav-ing a GID and list the physical factor on Axis

III as a comorbid condition. The relationship between GID and intersex

conditions is controversial topic that may be clarified with further research

being done in Germany.

Criterion 4: Significant distress

and impairment It is likely that many children, adolescents and adults struggle for a while to

consolidate their gender identity but eventually find an adap-tation that does

not impair their capacities to function socially, academically, or vocationally

as a member of their sex. These persons do not qualify for GID nor do those who

simply are not stereotypic in how they portray their gender roles. Mental

health professionals occasionally encounter parents who are disturbed by their

adolescent child’s gender roles. Parental distress is not the point of

criterion 4; this criterion refers to patient distress.

Diagnostic Criteria of Gender Identity Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (GIDNOS)

If an accurate community-based study of the gender-impaired could be conducted,

most cases would be diagnosed as GIDNOS. The diagnostician needs to understand

that gender identity de-velopment is a dynamic evolutionary process and

clinicians see people at crisis points in their lives. At any given time,

although it is clear that the patient has some form of GID, it may not be that

which is described in DSM-IV as GID. Here is one example: an adult female calls

herself a “neuter”. She wants her breasts re-moved because she hates to be

perceived as a woman. For 2 years she has been exploring “neuterdom” and “I am

definitely not in-terested in being a man!” If in 2 years, she evolves to meet

crite-rion 1, her current GIDNOS diagnosis will change.

GIDNOS is a large category designed to be inclusive of those with

unusual genders who do not clearly fit the criteria of GID. There is no

implication that if a patient is labeled GIDNOS that his or her label cannot

change in the future. GIDNOS would contain the many forms of transvestism:

masculine-appearing boys and teenagers with persistent cross-dressing (former

fet-ishistic transvestites) who are evolving toward GID, socially iso-lated men

who want to become a woman shortly after their wives or mothers die (secondary

transvestites) but express considerable ambivalence about the very matter they

passionately desired at their last visit, extremely feminized homosexuals

including those with careers as “drag queens” who seem to want to change their

sex when depressed, and so on. GIDNOS would also capture men who want to be rid

of their genitals without being feminized, uni-sexual females who imagine

themselves as males but who are terrified of any social expression of their

masculine gender iden-tity, hypermasculine lesbians in periodic turmoil over

their gen-der, and those women who strongly identify with both male and female

who lately want mastectomies. In using gender identity diagnoses, clinicians

need to remember that extremely masculine women or extremely feminine men are

not to be dismissed as ho-mosexual. “Lesbian” or “gay” is only a description of

orientation. They are more aptly described as also cross-gendered.

The Relationship of Gender Identity Disorders to Orientation

The usual clarity of distinctions between heterosexual, bisexual and

homosexual orientations rests upon the assumption that the biological sex and

psychological gender of the person and the partner are known. A woman who

designates herself as a les-bian is understood to mean she is erotically

attracted to other women. “Lesbian” loses its meaning if the woman says she

feels she is a man and lives as one.

She insists, “I am a heterosexual man; men are attracted to women as am I!” The

baffled clini-cian may erroneously think, “You are a female therefore you are a

lesbian!” DSM-IV suggests that adults with GIDs should be subgrouped according

to which sex the patient is currently sexu-ally attracted: males, females,

both, or neither. This makes sense for most gender patients because it is their

gender identity that is most important to them. Some are rigid about the sex of

those to whom they are attracted because it supports their idea about their

gender, others are bierotic and are not too concerned with their orientation,

still others have not had enough experiences to overcome their uncertainty

about their orientation. A few gender patients find all partners too

complicated and are only interested in themselves.

Treatment Options for the Gender Identity Disorders

The treatment of these conditions, although not as well-based on

scientific evidence as some psychiatric disorders, has been carefully

scrutinized by multidisciplinary committees of special-ists within the Harry

Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association for over 20 years. For more

details in managing an individual patient, please consult its “Standards of

Care” (Meyer et al., 2001). The

treatment of any GID begins after a careful

evaluation, including parents, other family members, spouses, psychometric

testing, and occasionally physical and laboratory examination. The details will

depend on age of the patient. It is possible, of course, to have a GID as well

as mental retardation, a psychosis, dysthymia, severe character pathology, or

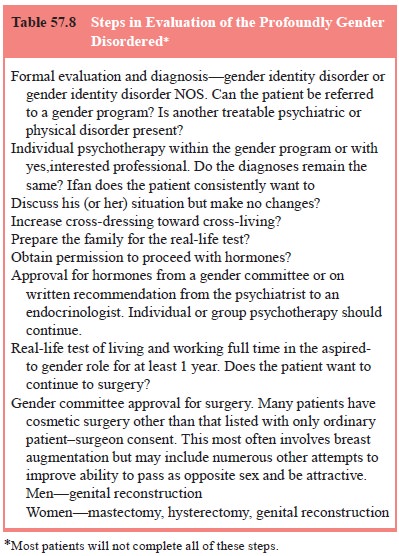

any other psychiatric diagnosis (Table 57.8).

Individual Psychotherapy

No one knows how to cure an adult’s gender problem. People who have lived long with profound cross-gender identifications do not get insight – either behaviorally modified or medicated – and find that they subsequently have a conventional gender identity. Psy-chotherapy is useful, nonetheless. If the patient is able to trust a therapist, there can be much to talk about: family relationships are often painful, barriers to relationship intimacy are profound, work poses many difficult issues, and the patient has to make monumental decisions. The central one is, “How am I going to live my life? Should I go through with cross-gender living, hor-mone therapy, mastectomy, or genital surgery?” The therapist can help the patient recognize the drawbacks and advantages of the various available options and to respect the initially unrecog-nized or unstated ambivalence. Completion of the gender trans-formation process usually takes longer than the patient desires, and the therapist can be an important source of support during and after these changes.

Group Therapy

Group therapy for gender-disordered people has the advantages of

allowing patients to know others with gender problems, of de-creasing their

social isolation, and of being among people who do not experience their

cross-gender aspirations and their past be-haviors as weird. Group members can

provide help with groom-ing and more convincing public appearances. The success

of these groups depends on the therapist’s skills in patient selection and

using the group process. Groups are generally only available in a few

specialized treatment programs.

“Real-life Test”

Living in the aspired-to-gender role – working, relating, conduct-ing

the activities of daily living – is a vital process that enables one of three

decisions: to abandon the quest, to simply live in this new role, or to proceed

with breast or genital surgery (Peterson and Dickey, 1995). Some clinicians use

the real-life test as a cri-terion for recommending hormones but this varies

because some patients’ abilities to present themselves in a new way is

definitely enhanced by prior administration of cross-sex hormones. The reason

for the real-life test is to give the patient, who created a transsexual

solution in fantasy, an opportunity to experience the solution in social

reality. Passing the real-life test is expected to be associated with improved

psychological function.

Hormone Therapy

Ideally, hormones should be administered by endocrinologists who have a

working relationship with a mental health team dealing with gender problems.

The effects of administration of estrogen to a biological male are: breast

development, testicular atrophy, decreased sexual drive, decreased semen volume

and fertility, softening of skin, fat redistribution in a female pattern and

decrease in spontaneous erections. Breast development is often the highest

concern to the patient. Because hair growth is not affected by estrogens,

electrolysis is often used to remove beard growth. Side effects within

recommended doses are minimal but hypertension, hyperglycemia, lipid

abnormalities, thrombophlebitis and hepatic dysfunction have been described.

The most dramatic effect of hormones is on the sense of well-being. Patients

report feeling calmer, happier knowing that their bodies are being

demasculinized and feminized. All results derive from open-labeled studies.

The administration of androgen to females results in an increased sexual

drive, clitoral tingling and growth, weight gain, and amenorrhea and

hoarseness. An increase in muscle mass may be apparent if weight training is

undertaken simultaneously. Hairgrowth depends on the patient’s genetic

potential. Androgens are administrated intramuscularly 200 to 300 mg/month and

are generally safe. It is prudent, however, periodically to monitor he-patic,

lipid and thyroid functioning. Most patients are delighted with their bodily

changes, although some are disappointed that they remain short, wide-hipped,

relatively hairless men with breasts that do not significantly regress.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention is the final external step. It should not occur

without mental health professional’s input, even when the patient provides a

heart-felt convincing set of reasons to bypass the real-life test, hormones and

therapeutic relationship. Genital surgery is expensive, time-consuming, at

times painful, and has frequent anatomic complications and functional

disappointments. Sur-gery can be expected to add further improvements in the

lives of patients: more social activities with friends and family, more

activity in sports, more partner sexual activity and improved vo-cational

status.

Males Surgery consists of penectomy, orchiectomy, vagino-plasty and fashioning

of a labia. The procedures used for the creation of a neovagina have evolved

over the years. Postopera-tively, the patient must maintain the patency of the

neovagina by initially constantly wearing and then periodically using a vaginal

dilator. Vaginal stenosis or shortening is a frequent complication. The quest

for an unmistakable feminine shape leads many young adult patients to

augmentation mammoplasty and the shaving of their cricoid cartilage.

Females The creation of a male-appearing chest through mas-tectomies and

contouring of the chest wall requires only a brief hospital stay. Patients are

usually immediately delighted with their new-found freedom, but their fantasies

of going shirtless are often not fulfilled due to the presence of two

noticeable hori-zontal chest scars. The creation of a neophallus that can

become erect, contain a functional urethra throughout its length (enabling

urination while standing), and pass as an unremarkable penis in a locker room

has been a significant surgical challenge. It is far from perfected. The

surgery is, however, the most time-consum-ing, technically difficult and

expensive of all the sex reassign-ment procedures. Erection is made possible by

a penile prosthe-sis. Many prudent patients consider themselves reassigned when

they have a hysterectomy, oophorectomy and mastectomy. Some just have a

mastectomy. They find a partner who understands the situation and supports the

idea of living with, and loving with, female genitals.

Related Topics