Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: The Senses

Sense of Smell

SENSE OF SMELL

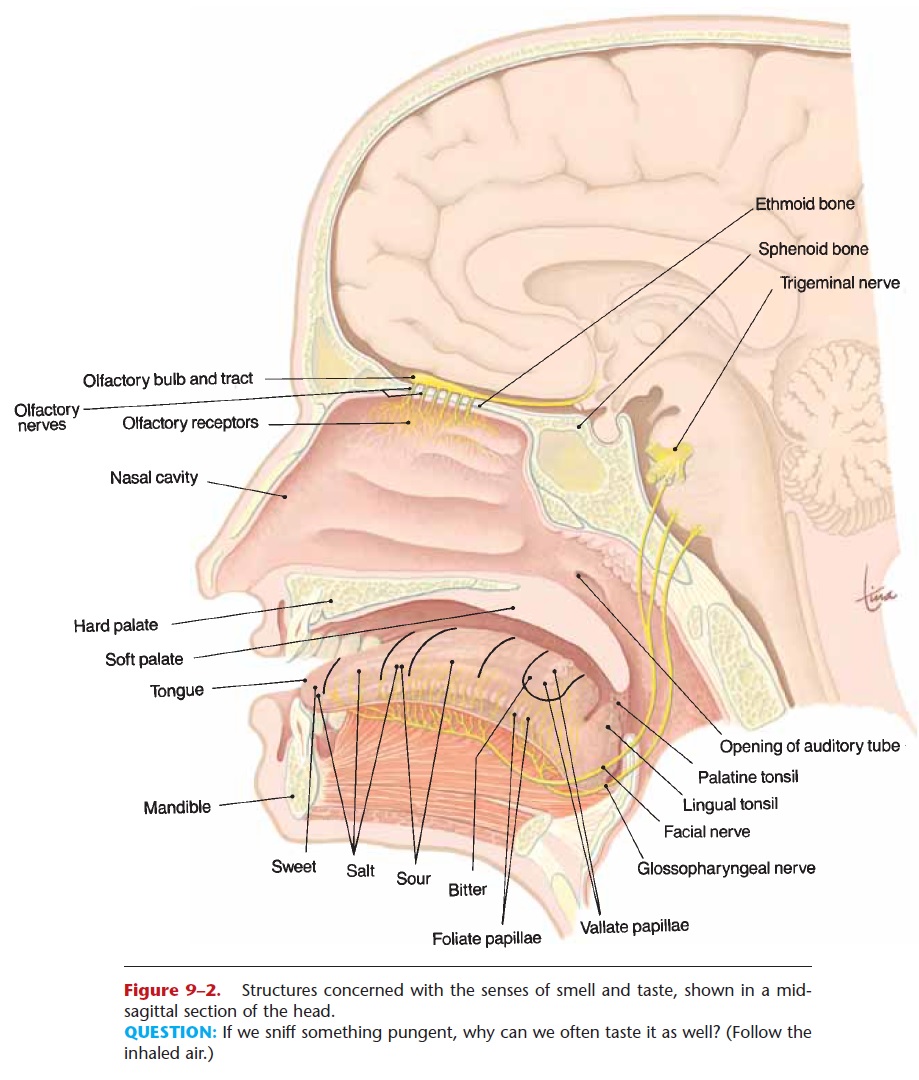

The receptors for smell (olfaction) are chemorecep-tors that detect vaporized chemicals that have been sniffed into the upper nasal cavities (see Fig. 9–2). Just as there are specific taste receptors, there are also specific scent receptors, and research indicates that humans have several hundred different receptors. When stimulated by vapor molecules, olfactory re-ceptors generate impulses carried by the olfactory nerves (1st cranial) through the ethmoid bone to the olfactory bulbs. The pathway for these impulses ends in the olfactory areas of the temporal lobes. Vapors may stimulate many combinations of receptors, and it has been estimated that the human brain is capable of distinguishing among 10,000 different scents.

Figure 9–2. Structures concerned with the senses of smell and taste, shown in a mid-sagittal section of the head.

QUESTION: If we sniff something pungent, why can we often taste it as well? (Follow the inhaled air.)

That may seem impressive, but the human sense of smell is very poorly developed compared to those of other animals. Dogs, for example, have a sense of smell about 2000 times more acute than that of peo-ple. (It has been said that most people live in a world of sights, whereas dogs live in a world of smells.) As mentioned earlier, however, much of what we call taste is actually the smell of food. If you have a cold and your nasal cavities are stuffed up, food just doesn’t taste as good as it usually does. Adaptation occurs rel-atively quickly with odors. Pleasant scents may be sharply distinct at first but rapidly seem to dissipate or fade, and even unpleasant scents may fade with long exposure.

Related Topics