Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Fishes as predators

Pursuit - Fishes as predators

Pursuit

Pursuit places a predator close enough to attack prey. Two dramatically different categories of predators have developed. One evolutionary course has favored species that maximize their speed while overtaking fleeing prey; the other course requires minimal aerobic output but a proliferation of deceptive tactics.

Cursorial, chasing predators are capable of high-speed sustained chases of rapidly swimming prey. Such fishes include the apex pelagic predators (lamnid sharks, tunas, billfishes). Morphologically, these are the most streamlined fishes, having bodies that are round in cross-section and taper to a thin, laterally keeled caudal peduncle, with the greatest body depth one-third of the way back from the head. The tail is narrow with a high aspect ratio (height : depth, Locomotion: movement and shape), and the median and paired fins typically fit into grooves or depressions during high-speed swimming. Nearer to shore, where prey can escape into structure, streamlining is sacrifi ced to allow for rapid braking and small radius turns. Bodies are more oval in cross-section, fins are larger, and tails broader. Predators such as salmons, snook (Centropomidae), Striped Bass (Moronidae), black basses (Centrarchidae), and large-bodied cichlids (e.g., Peacock Bass) are included here.

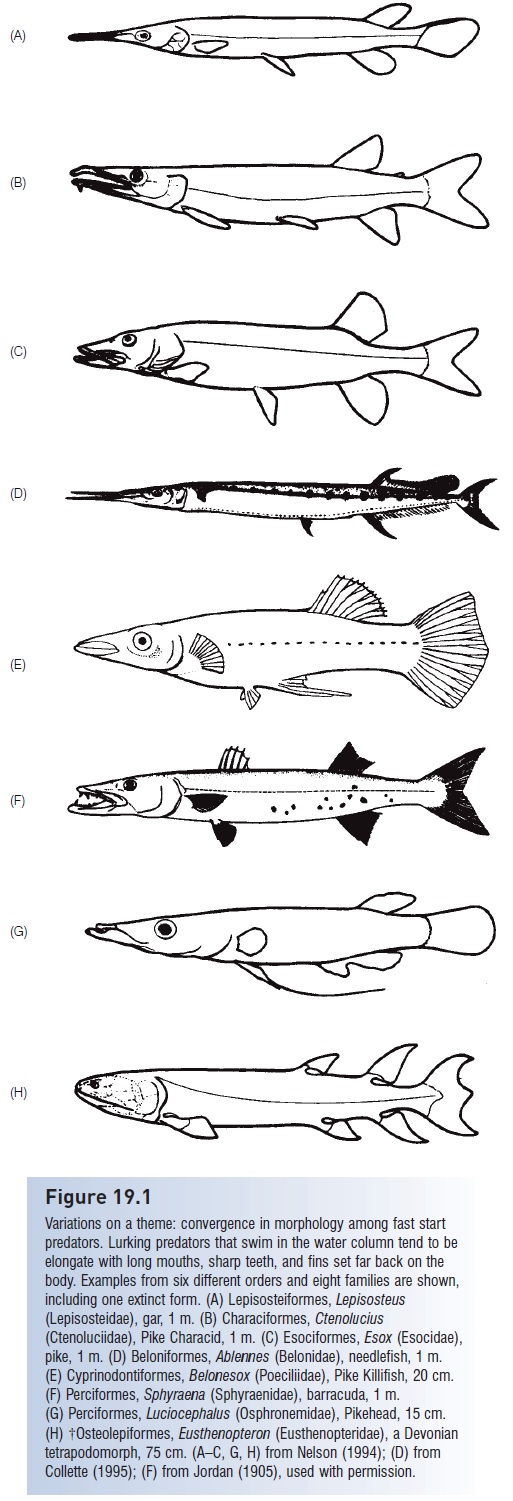

In lurking or lie-in-wait predators that swim above the bottom, pursuit is synonymous with attack. These fishes, which rely on fast start performance, have converged on a general body morphology that permits fast starts at a sacrifi ce in sustained speed and maneuverability. The group contains pikelike predators, including gars, pikes, pickerels, needlefishes, barracudas, and specialized fishes in such diverse families as the characins and cichlids (Fig. 19.1). These fishes have elongate, flexible bodies; long (“produced”) snouts with many sharp, often thin teeth; broad, symmetrical median fins placed far back on the body opposite one another; and relatively large caudal fins with low aspect ratios. The low body profile of these fishes serves additionally in that it evokes a slower response by prey than do predators with deeper body profiles (see Dominici & Blake 1997). These fishes typically hover high in the water column or lurk motionless on the edges of vegetation beds, relying on their camoufl age to gain access to prey. Additional piscivores that have converged on this morphology include the Australian endemic Long-finned Pike, Dinolestes lewini (Perciformes, Dinolestidae), and some of the world’s

Figure 19.1

Variations on a theme: convergence in morphology among fast start predators.

Lurking predators that swim in the water column tend to be elongate with long mouths, sharp teeth, and fins set far back on the body.

Examples from six different orders and eight families are shown, including one extinct form.

(A) Lepisosteiformes, Lepisosteus (Lepisosteidae), gar, 1 m.

(B) Characiformes, Ctenolucius (Ctenoluciidae), Pike Characid, 1 m.

(C) Esociformes, Esox(Esocidae), pike, 1 m.

(D) Beloniformes, Ablennes (Belonidae), needlefish, 1 m. (E) Cyprinodontiformes, Belonesox (Poeciliidae), Pike Killifish, 20 cm.

(F) Perciformes, Sphyraena (Sphyraenidae), barracuda, 1 m.

(G) Perciformes, Luciocephalus (Osphronemidae), Pikehead, 15 cm.

(H) †Osteolepiformes,Eusthenopteron (Eusthenopteridae), a Devoniantetrapodomorph, 75 cm. (A–C, G, H) from Nelson (1994);

(D) from Collette (1995);

(F) from Jordan (1905), used with permission.

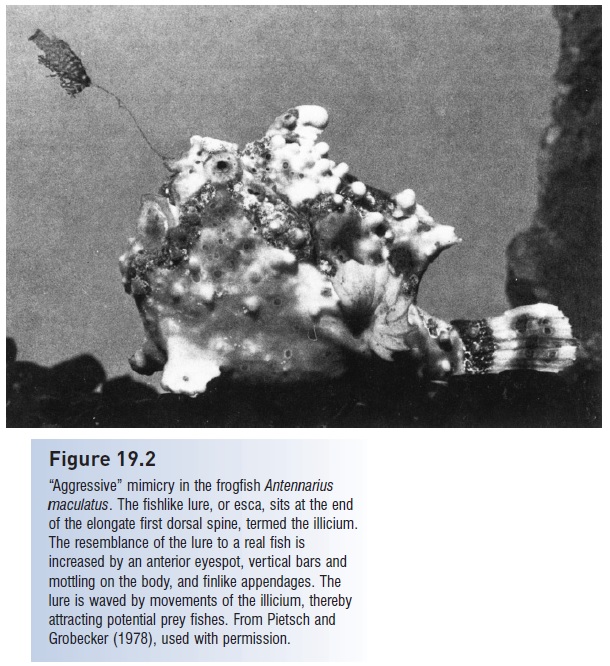

A class of predators has developed around the energy savings that can be gained if prey can be lured within range of attack. The success of this ploy depends on the prey not recognizing the predator until it is too late to flee, or on a willingness of the prey to approach the predator. Predators can induce prey to approach if the predator looks like something the prey might want to eat. This sort of deception, misnamed aggressive mimicry, can involve all or part of the predator’s body (e.g., Randall 2005). In goosefishes, anglerfishes, and frogfishes (Lophiiformes; The deep sea), the first dorsal spine is elongated and its end is highly modified into a species-typical esca or lure that resembles a small fish, shrimp, or worm (Fig. 19.2). The lure is wriggled in a lifelike manner, adding to the deception; in some species, the lure secretes a chemical attractant. The body of the predator is camouflaged to resemble the bottom or, in the case of deepsea anglers with bioluminescent lures, the dark surrounding waters. Small fishes approach the lure and are quickly inhaled by the large mouth, and their escape is often prevented by long, backward facing teeth (Pietsch & Grobecker 1978, 1987).

Figure 19.2

“Aggressive” mimicry in the frogfish Antennarius maculatus. The fishlike lure, or esca, sits at the end of the elongate first dorsal spine, termed the illicium. The resemblance of the lure to a real fish is increased by an anterior eyespot, vertical bars and mottling on the body, and finlike appendages. The lure is waved by movements of the illicium, thereby attracting potential prey fishes. From Pietsch and Grobecker (1978), used with permission.

Luring has evolved independently in other groups. A scorpionfish (Scorpaenidae) also uses a modified dorsal spine for a lure; hatchetfishes (Sternoptychidae), lanternfishes (Myctophidae), some anglerfishes (Ceratioidei), and stargazers (Uranoscopidae) have lures in their mouths; barbeled plunderfishes (Artedidraconidae) use chin barbels, chacid catfishes use maxillary barbels, and snake eels (Ophichthidae) have a lingual (tongue) lure; and in gulper eels (Eurypharyngidae) the tail tip is illuminated (Randall & Kuiter 1989). Nimbochromis livingstonii, a large predatory cichlid from Lake Malawi, Africa lures prey in a unique manner. N. livingstoniicapitalizes on the tendency of many small cichlids to scavenge on recently dead fishes. The predator lies on its side on the bottom and assumes a blotchy coloration typical of dead fish. When scavengers come to investigate and even pick at its body, the predator erupts from the bottom and engulfs them. This is the only known example of thanatosis or death feigning in fishes (McKaye 1981a). As a final twist, stonefish lie buried on the bottom and strike at prey fishes in a narrow zone directly above their mouths. If a potential prey fish swims between the mouth and the dorsal fin, the stonefish will raise its dorsal fin, chasing the fish back into the strike zone (Grobecker 1983).

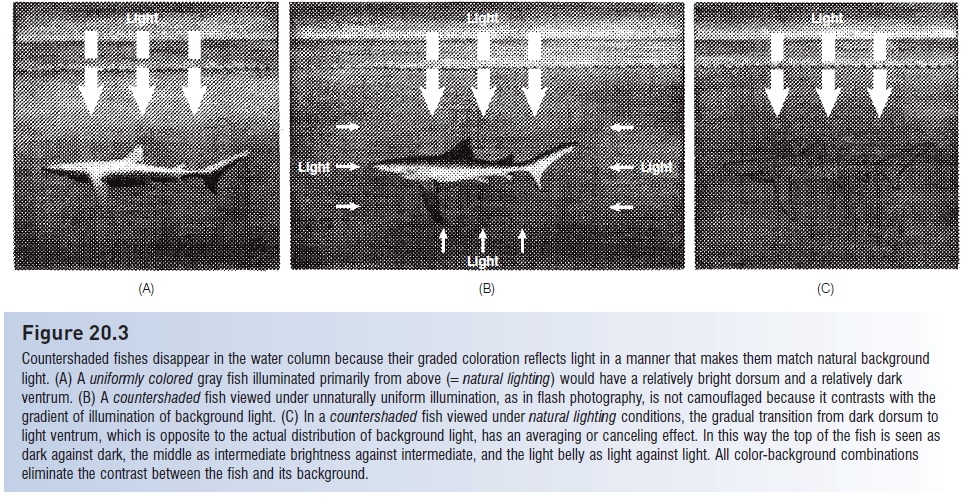

Approach to a prey fish is facilitated by camoufl age. Although most predators and their prey are countershaded or silvery, such coloration disguises a fish only when it is seen from the side. This is not the view that a prey fish has of an approaching predator. A convergent coloration trait shared by slow-stalking predators is the split-head color pattern (Barlow 1967). A dark or light line that contrasts with general body coloration runs from the tip of the snout along the midline between the eyes to the top of head or dorsal fin (see Fig. 20.2). This coloration is evident in pickerel (Esocidae), some soapfishes and seabasses (Serranidae), the tigerperchDatnioides (Lobotidae), the Leaffish, Polycentrus schomburgkii (Polycentridae), and some hawkfishes (Cirrhitidae), piscivores which are otherwise protectively colored and which approach their prey slowly and head-on. The split head pattern operates on the principle of disruptive coloration, dividing the head into halves and disrupting its outline. Prey may consequently require a moment to recognize the pattern as a whole, threatening head. Because

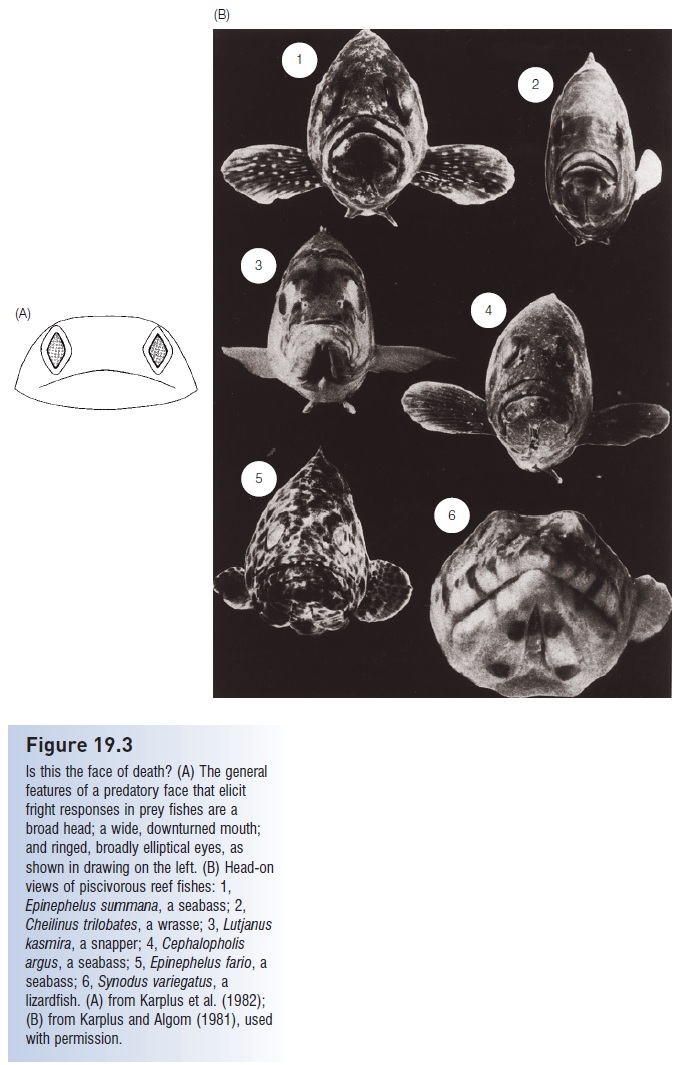

Figure 19.3

Is this the face of death? (A) The general features of a predatory face that elicit fright responses in prey fishes are a broad head; a wide, downturned mouth; and ringed, broadly elliptical eyes, as shown in drawing on the left. (B) Head-on views of piscivorous reef fishes: 1, Epinephelus summana, a seabass; 2,Cheilinus trilobates, a wrasse; 3, Lutjanus kasmira, a snapper; 4, Cephalopholis argus, a seabass; 5, Epinephelus fario, a seabass; 6, Synodus variegatus, a lizardfish. (A) from Karplus et al. (1982); (B) from Karplus and Algom (1981), used with permission.

Group hunting is comparatively rare in fishes. Apparent cooperative feeding, involving some form of coordinated herding or driving of prey by circling or advancing predators, has been observed in several shark species, including the Blacktip Reef, Lemon, and Oceanic Whitetip sharks (Carcharhinidae), sand tiger sharks (Odontaspididae), and thresher sharks (Alopiidae), the latter using their long caudal lobe for both herding and stunning prey (Motta & Wilga 2001; Motta 2004). Detailed observations of apparent cooperative feeding have been made on Sevengill Sharks, Notorynchus cepedianus, surrounding and then attacking seals off South Africa (Ebert 1991). Sevengills form a loose circle around the prey, and the circle gradually tightens until one and then the group of sharks attacks the seal. Other fishes suspected of engaging in cooperative feeding include piranhas, jacks, Yellowtail, Black Skipjack Tuna, Bluefin Tuna, and Sailfish (Bigelow & Schroeder 1948b; Hiatt & Brock 1948; Voss 1956; Potts 1980; Partridge 1982; Sazima & Machado 1990; Steele & Anderson 2006). None of these fishes cooperate to the extent observed in pack hunting mammals such as hyenas, wolves, lions, or killer whales.

Related Topics