Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Infectious Diseases

Preventing Infection in the Community

PREVENTING INFECTION IN THE COMMUNITY

Prevention and control

of infection in the community are goals shared by the CDC and state and local

public health depart-ments. Much of public health emphasis is placed on

prevention to avoid outbreaks and other situations that require control.

Methods of infection prevention include sanitation techniques (eg, water

purification, disposal of sewage and other potentially infectious materials),

regulated health practices (eg, handling, storage, packaging, preparation of

food by institutions), and im-munization programs. In the United States,

immunization pro-grams have markedly decreased the incidence of infectious

diseases.

Vaccination Programs

The goal of vaccination

programs is to use wide-scale efforts to prevent specific infectious diseases

from occurring in a popula-tion. Public health decisions about vaccine campaign

implemen-tation efforts are complex. Risks and benefits for the individual and

the community must be evaluated in terms of morbidity, mortality, and financial

benefit.

The most successful

vaccine programs are those for the pre-vention of smallpox, measles, mumps,

rubella, chicken pox, polio, diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus. Concerns that

smallpox may be reintroduced as an act of biowarfare have led to a decision

that medical first responders and selected others should again re-ceive small

pox vaccine.

More than 25 vaccines

are licensed in the United States. Vac-cines are made of antigen preparations

in a suspension and are in-tended to produce a human immune response to protect

the host from future encounters with the organism. No vaccine is com-pletely

safe for all recipients. Some people are allergic to the anti-gen or the

carrier substance. When live organisms are used as antigen, the actual disease

(often with a modified course) may fol-low. Contraindications on package

inserts of a vaccine must be heeded. These guidelines detail studied experience

with allergy and other complications and provide crucial information about

refrigeration, storage, dosage, and administration.

Variations to the

recommended vaccination schedule should be made on a case-by-case basis,

depending on the patient’s risk factors and ability to return for follow-up

vaccinations at the ap-pointed time. For example, although the first dose of

measles vac-cine is recommended at the age of 12 to 15 months, babies in

developing countries (where measles contributes significantly to childhood

morbidity and mortality) should be vaccinated at 9 months.

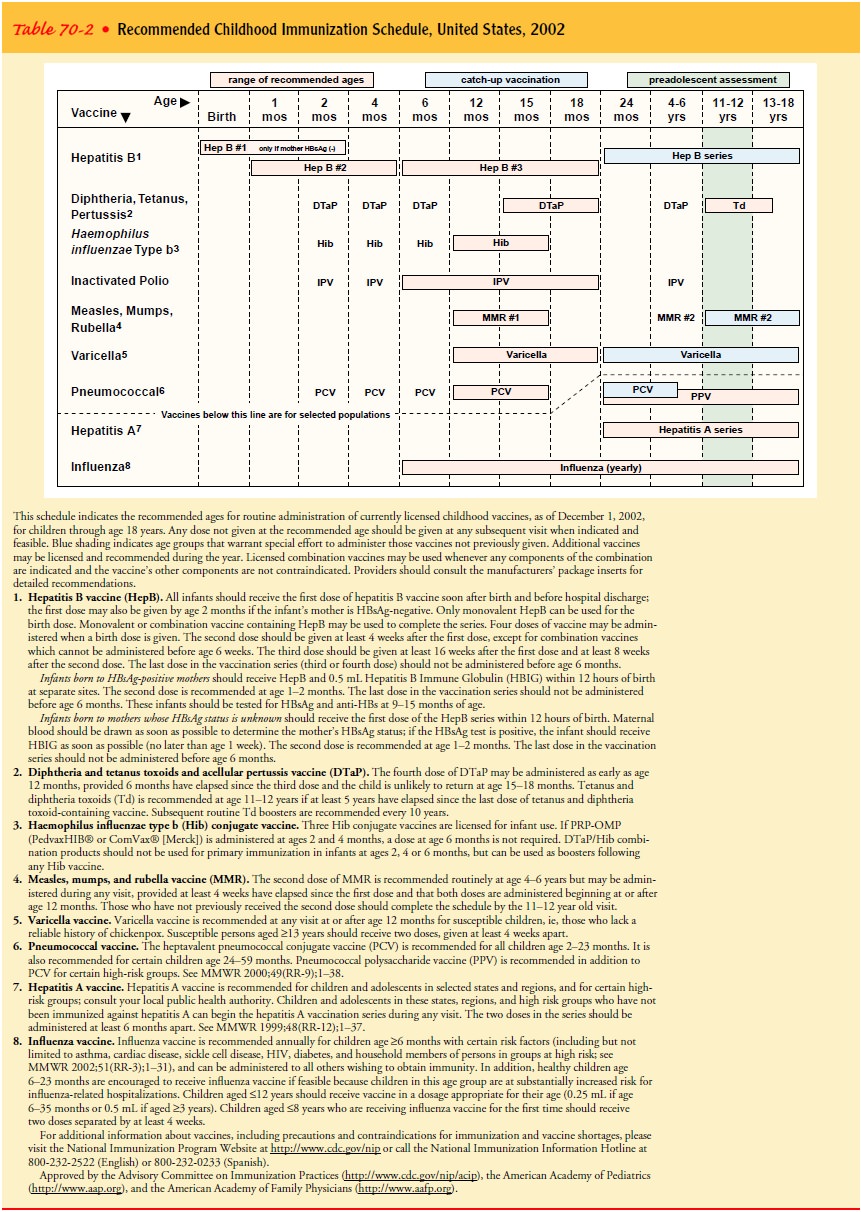

The standard recommended

vaccination schedule for infants and children as developed by the CDC is shown

in Table 70-2. The schedule is revised as epidemiologic evidence warrants, and

nurses are advised to consult the CDC to determine the most recent schedule.

Vaccine recommendations

for adults are designed to protect those with underlying diseases that increase

infection risk, those with potential for occupational exposure, and those who

may be exposed to infectious agents during travel. Immunosuppressed adults

(including those who have had splenectomy) should be vaccinated for

pneumococcus (Streptococcus pneumoniae),

menin-gococcus (Neisseria meningitidis),

and Haemophilus influenzae. Health care

workers should be immune to measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis B, and

varicella. It is strongly recommended that all of the previously described

adult groups and those with asthma or other chronic respiratory conditions

receive annual influenza vaccine.

Information about

individual vaccines or the most current vaccine schedules may be found on the

Internet. The CDC also provides a 24-hour telephone hotline (800-232-2522) for

information about routine pediatric or adult vaccine advice. Advice about op-timal

vaccination for travelers is available on the Internet, by phone

(877-FYI-TRIP), and by a toll-free fax number (888-232-3299) to request

information.

Nurses should ask

parents or adult vaccine recipients to pro-vide information about any problems

encountered after vaccina-tion. As mandated by law, a Vaccine Adverse Event

Reporting System (VAERS) form must be completed with the followinginformation:

type of vaccine received, timing of vaccination, onset of the adverse event,

current illnesses or medication, history of adverse events after vaccination

and demographic information about the recipient. Forms are obtained by phoning

1-800-822-7967 or through the Internet.

The incidence of

vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, mumps, rubella, and diphtheria,

is affected by immigration from developing countries. Vaccine campaigns in

developing countries are often financially and logistically constrained, and

immigrants from such areas may be more likely than U.S. residents to be

un-protected and may increase the potential pathways for epidemic spread.

Individual risk and epidemic risk are reduced when vac-cination campaigns reach

all communities, including those with a high proportion of immigrants.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patients who have experienced previous anaphylaxis or

similar reactions; patients who have developed encephalopathy within 7 days of

a previous diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) dose; and those who have

developed other moderate or severe sequelae after a previous dose should not

receive further doses. DTP is often deferred for the child who previously

developed a fever higher than 40°C (104°F) within 48 hours of vaccination or who had a seizure or

developed a shocklike state within 3 days of previous vaccination. Live

vaccines usually are not indicated for patients or close contacts of patients

with severe immuno-suppression (eg, HIV infection, leukemia, lymphoma,

generalized malignancy, significant corticosteroid use, use of

immuno-suppressive medications to prevent transplant rejection). The measles,

mumps, and rubella vaccine should not be administered to pregnant women.

MEASLES, MUMPS, AND RUBELLA VACCINE

Since the measles,

mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccines were li-censed, reported cases of these

diseases have decreased by more than 99% in the United States (ie, fewer than

500 cases per year since 1999). All public health departments are encouraged to

vig-orously promote vaccination for all children and for susceptible adults

unless contraindicated. Routine MMR vaccination should be given to children at

12 to 15 months of age, with repeat dosing at 4 to 6 years of age (Atkinson et al.,

2002).

All who work in health care should demonstrate immunity

to these three viruses by one of the following: birth date before 1957,

documented administration of two doses of vaccine, laboratory evidence of

immunity, or documentation of physician-diagnosed measles or mumps.

Side Effects.

Epidemiologic evidence supports that the risk

forside effects is greater in nonimmune vaccine recipients than in those

receiving repeat doses. Patients should be advised that fever, transient

lymphadenopathy, or hypersensitivity reaction might occur. Antipyretics may be

used to decrease the risk for fever, but aspirin should be avoided in infants

and children because of the risk for Reye’s syndrome.

VARICELLA (CHICKENPOX) VACCINE

Varicella zoster is the causative viral agent of chickenpox and herpes zoster. In its natural state, the varicella virus attacks most individuals as children, causing disseminated disease in the form of chickenpox. Chickenpox is often more severe in adults. Transmission occurs by the airborne and contact routes. With rare exception, varicella infects an individual only once.

The incubation period is about

2 weeks (range, 10 to 21 days). During a prodrome of general malaise (often

noticed about 2 days before the rash develops), the newly infected host is

capable of trans-mitting the virus to other susceptible contacts. Typically,

the rash is vesicular and pustular and spreads rapidly from few to many

le-sions in a matter of hours. New lesion formation continues for 2 to 3 days,

with lesions appearing at different stages throughout this time. By the fourth

symptomatic day, the lesions begin to dry, and new lesions usually do not

develop. Fever is common during the 4 to 6 days of rash progression. When the

lesions have crusted, the patient is no longer contagious to others.

Herpes zoster, also

known as shingles, is a localized rash caused by recurrent varicella. Vesicles

are restricted to areas supplied by single associated nerve groups. Varicella

may be transmitted from the rash of those with shingles to people who are

susceptible to varicella.

The varicella vaccine was first recommended as part of

the routine vaccine schedule in the United States in 1996. The vac-cine is

effective in preventing chickenpox in approximately 85% of those vaccinated and

significantly reduces the severity in almost all those who get the disease

despite vaccination (Atkinson et al., 2002). The vaccine should not be given to

those who have de-pressed immune function, are pregnant, have received blood

products in the past 6 months, or have demonstrated allergy to varicella

vaccine.

INFLUENZA VACCINE

Influenza is an acute

viral disease that predictably and periodically causes worldwide epidemics.

Epidemics occur every 2 to 3 years, with a highly variable degree of severity.

An average estimated ex-cess of 20,000 deaths per year have been attributed to

influenza or its sequelae (ie, pneumonia and cardiopulmonary collapse) in

vulnerable groups between 1977 and 1995 (Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention [CDC], 2001d).

Each year, a new vaccine

is available. It is composed of the three virus strains (usually two type A

influenza and one type B influenza strains) considered most likely to occur in

the coming season. When the presumed influenza agents have been correctly

anticipated and included in that year’s vaccine, vaccine offers approximately

70% to 90% protection for healthy children and young adults. Although less

effective in the elderly (as low as 30% to 40% in the frail elderly), it decreases

the severity of illness in those who do get infected, is 50% to 70% effective

in preventing pneumonia and hospitalization, and is 80% effective in

prevent-ing death. In extended care facilities, risk of transmission is greatly

reduced by vaccination of all residents (CDC, 2001d).

The Immunization

Practices Advisory Committee of the Public Health Service recommends annual

influenza vaccinations for the following groups at risk for influenza

complications: those older than 50 years of age, residents of extended care

facilities, those with chronic pulmonary or cardiovascular diseases, and those

with diabetes, immunosuppression, or renal dysfunction. Vaccination is also

advised for children (eg, those with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) who require

long-term aspirin therapy to reduce the likelihood of developing Reye’s

syndrome. Health care providers and household members of those in high-risk

groups should re-ceive the vaccine to reduce the risk of transmission to those

vul-nerable to influenza sequelae. Vaccine campaigns among health care workers

and patients should be intensified when there is evidence of community

influenza disease.

Related Topics