Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Spinal Anesthesia

Outline the advantages and disadvantages of catheter (continuous) spinal anesthesia

Outline the advantages and disadvantages of catheter (continuous)

spinal anesthesia.

In one form or another, catheter spinal

anesthesia tech-niques have provided excellent anesthesia for approximately 100

years. They offer all the benefits of single-injection spinal anesthesia plus

limitless duration of action. Continuous spinal anesthesia lapsed into disuse

with the advent of continuous epidural anesthesia, which offered relief from

the high incidence of PDPH. The relatively recent development of smaller

catheters designed for use in the subarachnoid space has led to renewed

interest in catheter spinal anesthesia. It may be selected over

single-injection spinal anesthesia for basically two reasons. Catheter spinal

anesthesia offers the option for slow incremental dosing intended to minimize

hemodynamic changes. It also extends the duration of anesthesia for operations

expected to outlast the course of single-dose methods.

Advances in technology and pharmacology have

brought us to the present state of the art. In the past, catheter spinal

anesthesia was performed with large-bore needles and catheters designed for

epidural use. Presently there are catheters ranging in size from 24- to

32-gauge. These catheters are intended for insertion through 20- to 27-gauge

needles in an attempt to reduce the incidence of PDPH. Establishment of

continuous spinal anesthesia is usually simple. A needle is placed in the

subarachnoid space, and the difference from skin to the space is estimated by

subtracting the length of the exposed needle from the needle’s total length.

The catheter is passed through the needle until its tip resides at the needle

bevel. This is usually a distance of 10 cm. The catheter is then advanced 3 cm

into the subarach-noid space. Inability to thread the catheter beyond the

needle bevel generally results from obstruction by one of several anatomic

structures. Combinations of needle manipulation, such as rotation and/or

advancement and/or withdrawal, generally allow for passage into the space. If

these maneuvers fail, the procedure is repeated at another interspace.

With the catheter properly inserted into the

subarach-noid space, slowly withdraw the needle over the catheter with one hand

as the other hand applies slight pressure in the opposite direction. Recall the

distance from the skin to the space and add 3 cm, this being the length of the

catheter which should be inserted into the patient’s back. Gently aspirate CSF

through the catheter to confirm proper placement.

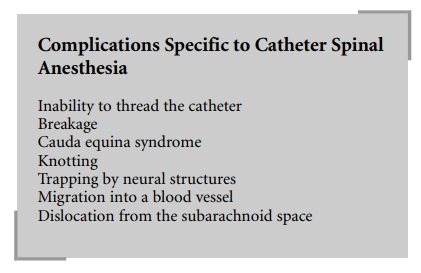

The recognized complications of continuous

spinal anesthesia include all those attributed to single-injection methods plus

those summarized below.

One of the most frequent and frustrating

complications of catheter techniques is the inability to pass a catheter into

the proper location. The incidence of inability to thread spinal catheters

approximates 8%. The potential causes of this problem are numerous and poorly

defined for any individual patient.

Experience with epidural catheters has shown

occasional breakage during insertion and removal. Spinal catheter breakage

during attempted insertion generally occurs when catheters are withdrawn

through the needle. An entire catheter segment may be sheared off by this

maneuver. Even a partial cut in the catheter could reduce its tensile strength,

predisposing to breakage during removal in the postoperative period. Inability

to pass a catheter must result in simultaneous removal of both needle and

catheter from the back. The procedure is then repeated at the same interspace

or another one.

Catheter breakage during removal from the back

is generally heralded by catheter elongation. Stretching can be considered a

warning sign of imminent danger. Break strengths of one presently available

24-gauge spinal catheter and a commonly used 20-gauge epidural catheter are

3.55 lb (1.6 kg) and 6.35 lb (2.9 kg), respectively. This is a very narrow

range, placing most catheters at risk of snapping during removal. Consequently,

removal must take place with the vertebrae flexed to the same degree as they

were during insertion. This maneuver attempts to realign the various ligaments,

minimizing their grip on the catheter.

Catheter breakage is a difficult problem to

deal with. If breakage occurs close to the skin, then superficial dissection

under local anesthesia may allow for isolation of the catheter. It can be

grasped with a clamp and gently removed. If the catheter is severed in deep

tissues, it may be left in situ. The risk of infection is small, because it is

placed under strictly sterile conditions. General anesthesia and laminectomy to

retrieve the catheter may place the patient at higher risk for associated

complications than leaving it in place. A moral and ethical obligation exists

to inform the patient of this compli-cation in the rare event of its occurrence.

Another theoretical problem is a small segment

of catheter floating freely within the subarachnoid space, which could migrate

cephalad and produce significant complica-tions. This situation may present a

more compelling reason for surgical removal than a catheter which is held

firmly by ligaments.

Another unusual but noteworthy complication of

catheter spinal anesthesia is cauda equina syndrome. In 1991, Rigler et al.

reported 4 cases of cauda equina syndrome occurring after catheter spinal

anesthesia. Evidence of sub-arachnoid block was achieved in all cases, and

additional doses were administered to raise the level of analgesia. The total

initial dose of local anesthetic was generally greater than that administered

in a single bolus dose through a spinal needle. The authors speculate that

pooling of large doses of local anesthetic resulted in neurotoxicity.

Later in 1991, Lambert and Hurley described a

model that demonstrated hyperbaric and isobaric lidocaine loculation in the

sacral and lower lumbar regions. In the event of inadequate local anesthetic

spread following injec-tion of 2% isobaric lidocaine (40 mg) they suggest the

addition of 1–2 mL of hypobaric 0.375% bupivacaine.

Hypobaric 0.375% bupivacaine is readily

prepared by dilu-tion of 0.75% plain bupivacaine with an equal volume of

distilled water. This technique should allow spread of local anesthetic into

the upper lumbar area while limiting local anesthetic exposure to only 40 mg of

lidocaine and 7.5 mg of bupivacaine. Such low doses of anesthetic would be

expected to place patients at low risk for cauda equina syndrome. This

combination of isobaric and hypobaric solutions is logical, based on observed

subarachnoid spread of these solutions.

Catheters can curl on themselves and tighten into

knots when withdrawn. Such occurrence could prevent with-drawal

postoperatively, because the knot would be too large to fit through the dural

hole. A worse circumstance could occur if a nerve were entrapped by the knot.

In this case, one would expect radicular pain during attempted catheter

removal. Catheter curling is most likely to happen if excessive lengths are

inserted into the subarachnoid space. To prevent this, never advance more than

3 cm of catheter beyond the needle tip.

Migration into a blood vessel is generally of

little conse-quence. The usual doses of local anesthetic delivered for spinal

anesthesia (approximately 50 mg of lidocaine) are less than those purposefully

administered intravenously for the treatment of premature ventricular contractions

(approximately 100 mg of lidocaine).

Dislocation from the subarachnoid space will

result in epidural placement. The small doses of local anesthetic generally

employed for spinal anesthesia will yield minimal or no blockade following

administration into the epidural space. It is theoretically possible, although

highly unlikely, that a catheter intended for the subarachnoid space could

lodge in the subdural space. The subsequent delivery of local anesthetic would

then cause either segmental anesthesia or massive sympathetic, sensory, and

motor blockade, depend-ing on the dose administered into the subdural space.

A century of spinal anesthesia has witnessed

advances in pharmacology and technology culminating in the use of small

catheters for placement in the subarachnoid space. Although spinal anesthesia,

like general anesthesia, is fraught with potential problems, its judicious

application has benefited innumerable patients. Continuous spinal anesthesia

represents a double-edged sword. It offers advantages over general anesthesia

and catheter epidural anesthesia but is associated with its own potential

compli-cations. With knowledge of these potential problems and careful

application of the procedure, catheter spinal anesthesia remains a safe and desirable

technique.

Related Topics