Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : Code Generation

Optimization of Basic Blocks

Optimization of Basic Blocks

1 The DAG Representation of Basic Blocks

2 Finding Local Common Subexpressions

3 Dead Code Elimination

4 The Use of Algebraic Identities

5 Representation of Array References

6 Pointer Assignments and Procedure Calls

7 Reassembling Basic Blocks From DAG's

8 Exercises for Section 8.5

We can often obtain a substantial

improvement in the running time of code merely by performing local optimization within each basic

block by itself. More thorough global

optimization, which looks at how information flows among the basic blocks of a

program, is covered in later chapters, starting with Chapter 9. It is a complex

subject, with many different techniques to consider.

1. The DAG Representation of

Basic Blocks

Many important techniques for

local optimization begin by transforming a basic block into a DAG (directed

acyclic graph). In Section 6.1.1, we introduced the DAG as a representation for

single expressions. The idea extends naturally to the collection of expressions

that are created within one basic block. We construct a DAG for a basic blockas

follows:

1. There is a node in the DAG for each of the initial values of the

variables appearing in the basic block.

2. There is

a node N associated with

each statement s

within the block. The children of

N are those nodes corresponding to statements that are the last definitions,

prior to s, of the operands used by s.

3. Node N is labeled by the operator applied at s,

and also attached to N is the list of variables for which it is the last definition

within the block.

4. Certain nodes

are designated output nodes.

These are the nodes whose variables

are live on

exit from the block; that

is, their values may be used later, in another block of the

flow graph. Calculation of these "live variables" is a matter for

global flow analysis, discussed in Section 9.2.5.

The DAG representation of a basic

block lets us perform several code-improving transformations on the code

represented by the block.

We can eliminate local common subexpressions, that is,

instructions that compute a value that has already been computed.

We can eliminate dead code, that is, instructions that

compute a value that is never used.

We can reorder statements that do

not depend on one another; such reordering may reduce the time a temporary

value needs to be preserved in a register.

We can apply algebraic laws to reorder operands of three-address

instruc-tions, and sometimes thereby simplify the computation.

2. Finding Local Common

Subexpressions

Common subexpressions can be

detected by noticing, as a new node M

is about to be added, whether there is an existing node N with the same children, in the same order, and with the same

operator. If so, TV computes the same value as M and may be used in its place. This technique was introduced as

the "value-number" method of detecting common subexpressions in

Section 6.1.1.

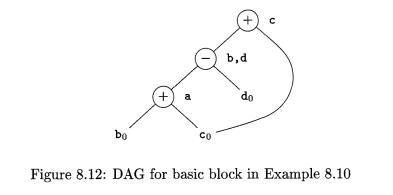

Example 8

. 1 0 : A DAG for the block

a

= b +

c

b = a - d c = b + c

d = a – d

is shown in Fig. 8.12. When we

construct the node for the third statement c = b + c, we know that the use of b

in b + c refers to the node of Fig. 8.12 labeled -, because that is the most recent definition of

b. Thus, we do not confuse the values computed at statements one and three.

However, the node corresponding to the fourth

statement d = a - d has the operator - and the nodes with attached variables a and do

as children. Since the operator and the children are the same as those for the

node corresponding to statement two, we do not create this node, but add d to

the list of definitions for the node labeled —. •

It might appear that, since there are only three nonleaf nodes in the

DAG of Fig. 8.12, the basic block in Example 8.10 can be replaced by a block

with only three statements. In fact, if b is not live on exit from the block,

then we do not need to compute that variable, and can use d to receive the

value represented by the node labeled —. in Fig. 8.12. The block then becomes

However, if both b and d are live on exit, then a

fourth statement must be used to copy the value from one to the other.1

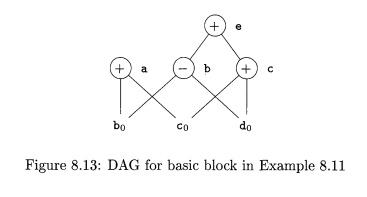

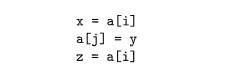

E x a m p l e 8.11: When we

look for common subexpressions, we really are look-ing for expressions that are

guaranteed to compute the same value, no matter how that value is computed.

Thus, the DAG method will miss the fact that the expression computed by the

first and fourth statements in the sequence

a = b + c;

b = b - d

c = c + d

e = b + c

is the same, namely bo 4- en. That is, even though b and c both change

between the first and last statements, their sum remains the same, because b + c = (b - d) + (c + d). The DAG for this sequence is shown in Fig. 8.13,

but does not exhibit any common

subexpressions. However, algebraic identities applied to the DAG, as discussed

in Section 8.5.4, may expose the equivalence.

3. Dead Code Elimination

The operation on DAG's that

corresponds to dead-code elimination can be im-plemented as follows. We delete

from a DAG any root (node with no ancestors) that has no live variables attached.

Repeated application of this transformation will remove all nodes from the DAG

that correspond to dead code.

Example 8.12: If, in

Fig. 8.13, a and b are live but c and e are not, we can immediately remove the root

labeled e. Then, the node labeled c becomes a root and can be removed. The

roots labeled a and b remain, since they each have live variables attached. •

4. The Use of Algebraic

Identities

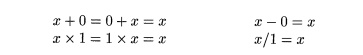

Algebraic identities represent another important class of optimizations

on basic blocks. For example, we may apply arithmetic identities, such as

to eliminate computations from a basic block.

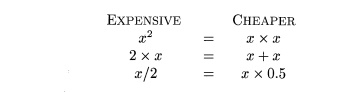

Another class of algebraic optimizations includes local reduction in strength, that is,

replacing a more expensive operator by a cheaper one as in:

A third class of related optimizations is constant folding. Here we evaluate

constant expressions at compile time and replace the constant expressions by

their values.2 Thus the expression 2 * 3 . 1 4 would be replaced by 6 . 2 8 . Many

constant expressions arise in practice because of the frequent use of symbolic

constants in programs.

The DAG-construction process can help us apply

these and other more general algebraic transformations such as commutativity

and associativity. For example, suppose the language reference manual specifies

that * is commutative; that is, x*y =

y*x. Before we create a new node labeled * with left child M and right child N, we always check whether such a node already exists. However,

because * is commutative, we should then check for a node having operator *,

left child N, and right child M.

The relational operators such as < and —

sometimes generate unexpected common subexpressions. For example, the condition

x > y can also be tested by

subtracting the arguments and performing a test on the condition code set by

the subtraction.3 Thus, only one node of the DAG may need to be generated for x — y and x > y.

Associative laws might also be applicable to expose common

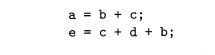

subexpressions. For example, if the source code has the assignments

the following intermediate code might be generated:

using both the associativity and commutativity of

+.

The compiler writer should examine the language reference manual care-fully

to determine what rearrangements of computations are permitted, since (because

of possible overflows or underflows) computer arithmetic does not al-ways obey

the algebraic identities of mathematics. For example, the Fortran standard

states that a compiler may evaluate any mathematically equivalent

expression, provided that the integrity

of parentheses is not violated. Thus, a

compiler may evaluate x * y — x * z a,s x * (y - z), but it may not evaluate a

+ (6 — c) as (a + b) — c. A Fortran compiler must therefore keep track of where

parentheses were present in the source language expressions if it is to

optimize programs in accordance with the language definition.

5. Representation of Array

References

At first glance, it might appear that the array-indexing instructions

can be treated like any other operator. Consider for instance the sequence of

three-address statements:

If we think of a [ i ] as an

operation involving a and i, similar to

a + i, then it might appear as if the two uses of a [ i ] were a common

subexpression. In that case, we might be tempted to "optimize" by

replacing the third instruction z = a [ i ]

by the simpler z = x. However, since j could equal i, the middle statement may in

fact change the value of a [ i ] ; thus, it is not legal to make this

change.

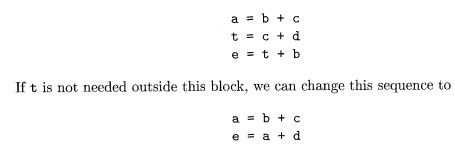

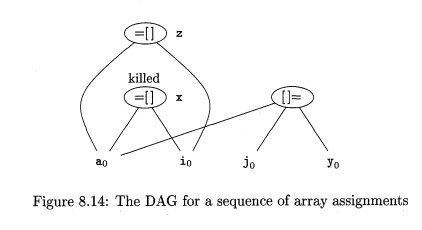

The proper way to represent array accesses in a DAG is as follows.

1. An assignment from an array, like x

= a [ i ] , is represented by creating a node with operator =[] and two

children representing the initial value of the array, a0 in this case, and the index i. Variable x becomes a label of this new

node.

2. An assignment to an array, like a [ j ] = y, is represented by a new node with operator

[]= and three children representing a 0 , j and y. There is no variable

labeling this node. What is different is that the creation of this node

kills all currently constructed nodes

whose value depends on a 0 . A node that has been killed cannot receive any more labels; that is,

it cannot become a common subexpression.

Example 8

. 1 3 : The DAG for the basic block

x = a [ i ]

a [ j ] = y

z = a [ i ]

is shown in Fig- 8.14. The node N for x is created

first, but when the node labeled [ ] = is created, N is killed. Thus, when the node for z is created, it

cannot be identified with N, and a new node with the same operands a0 and i0

must be created instead.

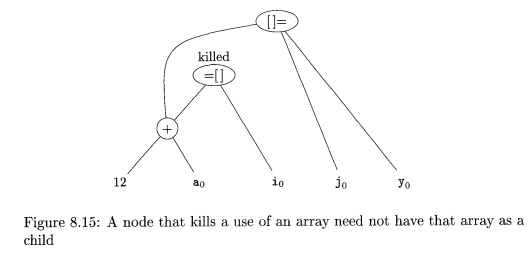

Example 8 . 14: Sometimes, a node must be killed

even though none of its children have an array like a0 in Example 8.13 as

attached variable. Likewise, a node can kill if it has a descendant that is an

array, even though none of its children are array nodes. For instance, consider

the three-address code

b = 12 + a

x = b [ i ]

b [ j ] = y

What is happening here is that, for efficiency

reasons, b has been defined to be a position in an array a. For example, if the

elements of a are four bytes long, then b represents the fourth element of a.

If j and i represent the same value, then b [ i ] and b [ j ] represent the

same location. Therefore it is important to have the third instruction, b [ j ]

= y, kill the node with x as its attached variable. However, as we see in Fig.

8.15, both the killed node and the node that does the killing have cio as a

grandchild, not as a child.

6. Pointer Assignments and

Procedure Calls

When we assign indirectly through a pointer, as in

the assignments

x = *p

*q = y

we do not know what p or q point to. In effect, x =

*p is a use of every variable whatsoever, and *q = y is a possible assignment

to every variable. As a consequence, the operator =* must take all nodes that

are currently associated with identifiers as arguments, which is relevant for

dead-code elimination. More importantly, the *= operator kills all other nodes

so far constructed in the DAG.

There are global pointer analyses

one could perform that might limit the set of variables a pointer could

reference at a given place in the code. Even local analysis could restrict the

scope of a pointer. For instance, in the sequence

p = &x

*p = y

we know that x, and no other variable, is given the

value of y, so we don't need to kill any node but the node to which x was

attached.

Procedure calls behave much like

assignments through pointers. In the absence of global data-flow information,

we must assume that a procedure uses and changes any data to which it has

access. Thus, if variable x is in the scope of a procedure P, a call to P both uses the node with attached

variable x and kills that node.

7. Reassembling Basic Blocks From

DAG's

After we perform whatever

optimizations are possible while constructing the DAG or by manipulating the

DAG once constructed, we may reconstitute the three-address code for the basic

block from which we built the DAG. For each

node that has one or more attached variables, we construct a

three-address statement that computes the value of one of those variables. We

prefer to compute the result into a variable that is live on exit from the

block. However, if we do not have global live-variable information to work

from, we need to assume that every variable of the program (but not temporaries

that are generated by the compiler to process expressions) is live on exit from

the block.

If the node has more than one

live variable attached, then we have to in-troduce copy statements to give the

correct value to each of those variables. Sometimes, global optimization can

eliminate those copies, if we can arrange to use one of two variables in place

of the other.

Example 8 . 1 5 : Recall the DAG of Fig. 8.12. In the discussion following Example 8.10, we decided that if b is

not live on exit from the block, then the three statements

a = b + c

d = a - d

c = d + c

suffice to reconstruct the basic

block. The third instruction, c = d

+ c, must use d as an operand rather

than b, because the optimized block never computes b.

If both b and d are live on exit, or if we are not sure whether or not

they are live on exit, then we need to compute b as well as d. We can do so

with the sequence

a = b + c

d = a - d

b = d

c = d + c

This basic block is still more efficient than the

original. Although the number of instructions is the same, we have replaced a

subtraction by a copy, which tends to be less expensive on most machines.

Further, it may be that by doing a global analysis, we can eliminate the use of

this computation of b outside the block by replacing it by uses of d. In that

case, we can come back to this basic block and eliminate b = d later.

Intuitively, we can eliminate this copy if wherever this value of b is used, d

is still holding the same value. That situation may or may not be true,

depending on how the program recomputes d. •

When reconstructing the basic block from a DAG, we

not only need to worry about what variables are used to hold the values of the

DAG's nodes, but we also need to worry about the order in which we list the

instructions computing the values of the various nodes. The rules to remember

are

1. The order of instructions must respect the order of nodes in the DAG.

That is, we cannot compute a node's value until we have computed a value for

each of its children.

2. Assignments

to an array must follow all previous assignments to, or eval-uations from, the

same array, according to the order of these instructions in the original basic

block.

Evaluations of array elements

must follow any previous (according to the original block) assignments to the

same array. The only permutation allowed is that two evaluations from the same

array may be done in either order, as long as neither crosses over an

assignment to that array.

Any use of a variable must follow

all previous (according to the original block) procedure calls or indirect

assignments through a pointer.

Any procedure call or indirect

assignment through a pointer must follow all previous (according to the

original block) evaluations of any variable.

That is, when reordering code, no statement may

cross a procedure call or assignment through a pointer, and uses of the same

array may cross each other only if both are array accesses, but not assignments

to elements of the array.

8. Exercises for Section 8.5

Exercise

8 . 5 . 1 :

Construct the DAG for the basic block

d = b * c

e = a + b

b = b * c

a = e - d

Exercise

8 . 5 . 2: Simplify the three-address code of Exercise

8.5.1, assuming

Only a is

live on exit from the block.

a, b, and c

are live on exit from the block.

Exercise

8 . 5 . 3 : Construct the basic block for

the code in block B6 of Fig. 8.9.

Do not forget to include the comparison i < 10.

Exercise

8 . 5 . 4 : Construct the basic block for the

code in block B3 of Fig. 8.9.

Exercise

8 . 5 . 5 : Extend Algorithm 8.7 to process

three-statements of the form

a) a [ i ]

= b

b) a = b [

i ]

a = *b

*a = b

Exercise

8 . 5 . 6 : Construct the DAG for the basic block

a [ i ] = b

*p = c

= a [ j ]

= *p

*p = a [ i ]

on the assumption that

p can point anywhere.

p can point only to b or d.

Exercise 8 . 5 . 7 : If a pointer or array

expression, such as a [ i ] or *p is assigned and then used, without the

possibility of being changed in the interim, we can take advantage of the

situation to simplify the DAG. For example, in the code of Exercise 8.5.6,

since p is not assigned between the second and fourth statements, the statement

e = *p can be replaced by e = c, regardless of what p points to. Revise the

DAG-construction algorithm to take advantage of such situations, and apply your algorithm to the code of

Example 8.5.6.

Exercise 8 . 5 . 8 : Suppose a basic block is formed from the C

assignment statements

x = a

+ b + c

+ d + e

+ f;

y = a

+ c + e;

Give the three-address statements

(only one addition per statement) for this block.

Use the associative and

commutative laws to modify the block to use the fewest possible number of

instructions, assuming both x and y are live on exit from the block.

Related Topics