Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Trauma

Nursing Process: The Patient With a Brain Injury

NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH A BRAIN INJURY

Assessment

Depending on the

patient’s neurologic status, the nurse may elicit information from the patient,

family, or witnesses or from emer-gency rescue personnel (Munro, 2000).

Although it may not be possible to obtain all usual baseline data initially, the

immediate health history should include the following questions:

·

When did the injury occur?

·

What caused the injury? A

high-velocity missile? An object striking the head? A fall?

·

What was the direction and

force of the blow?

Since a history of unconsciousness or amnesia after a

head in-jury indicates a significant degree of brain damage, and since changes

that occur minutes to hours after the initial injury can re-flect recovery or

indicate the development of secondary brain damage, the nurse should try to

determine if there was a loss of consciousness, what the duration of the

unconscious period was, and if the patient could be aroused.

In addition to questions that establish the nature of the

injury and the patient’s condition immediately after the injury, the nurse

should examine the patient thoroughly. This assessment should include

determining the patient’s LOC, ability to respond to verbal commands (if

conscious), response to tactile stimuli (if unconscious), pupillary response to

light, status of corneal and gag reflexes, motor function, and Glasgow Coma

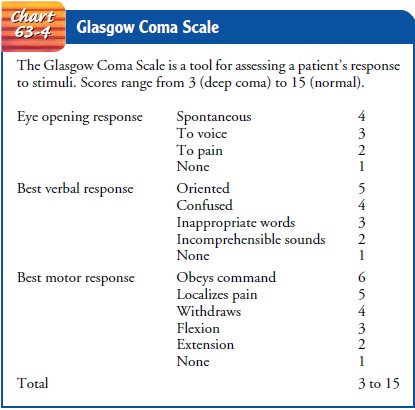

Scale score (Chart 63-4).

Additional detailed neurologic and systems assessments are made initially and at frequent intervals throughout the acute phase of care (Dibsie, 1998). The baseline and ongoing assess-ments are critical nursing interventions for the brain-injured patient, whose condition can worsen dramatically and irrevocably if subtle signs are overlooked. More information on assessment is provided below and in Figure 63-5 and Table 63-1.

Diagnosis

NURSING DIAGNOSES

Based on the assessment data, the patient’s major nursing

diag-noses may include the following:

·

Ineffective airway clearance

and impaired gas exchange re-lated to brain injury

·

Ineffective cerebral tissue

perfusion related to increased ICP and decreased CPP

·

Deficient fluid volume related

to decreased LOC and hor-monal dysfunction

·

Imbalanced nutrition, less

than body requirements, related to metabolic changes, fluid restriction, and

inadequate intake

·

Risk for injury (self-directed

and directed at others) related to seizures, disorientation, restlessness, or

brain damage

·

Risk for imbalanced

(increased) body temperature related to damaged temperature-regulating

mechanism

·

Potential for impaired skin

integrity related to bed rest, hemiparesis, hemiplegia, and immobility

·

Disturbed thought processes

(deficits in intellectual function, communication, memory, information

processing) related to brain injury

·

Potential for disturbed sleep

pattern related to brain injury and frequent neurologic checks

·

Potential for compromised

family coping related to un-responsiveness of patient, unpredictability of

outcome, pro-longed recovery period, and the patient’s residual physical and

emotional deficit

·

Deficient knowledge about

recovery and the rehabilitation process

The nursing diagnoses for the unconscious patient and the patient with increased ICP also apply.

COLLABORATIVE PROBLEMS/POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Based on all the assessment data, the major complications

include the following:

·

Decreased cerebral perfusion

·

Cerebral edema and herniation

·

Impaired oxygenation and

ventilation

·

Impaired fluid, electrolyte,

and nutritional balance

·

Risk of post-traumatic

seizures

Planning and Goals

The goals for the patient may include maintenance of a

patent airway, adequate CPP, fluid and electrolyte balance, adequate

nutritional status, prevention of secondary injury, maintenance of normal body

temperature, maintenance of skin integrity, im-provement of cognitive function,

prevention of sleep deprivation, effective family coping, increased knowledge

about the rehabili-tation process, and absence of complications.

Nursing Interventions

The nursing interventions for the patient with a head

injury are extensive and diverse; they include making nursing assessments,

setting priorities for nursing interventions, anticipating needs and

complications, and initiating rehabilitation.

MONITORING FOR DECLINING NEUROLOGIC FUNCTION

The importance of ongoing assessment and monitoring of

the brain-injured patient cannot be overstated. The following para-meters are

assessed initially and as frequently as the patient’s condition requires. As

soon as the initial assessment is made, the use of a neurologic flow chart is

started and maintained.

Level of Consciousness

The LOC is regularly assessed because changes in it precede all other changes in vital and neurologic signs. The Glasgow Coma Scale, which is used to assess LOC, is based on the three criteria of eye opening, verbal responses, and motor responses to verbal commands or painful stimuli. It is particularly useful for monitoring changes during the acute phase, the first few days after a head injury. It does not take the place of an in-depth neurologic assessment; rather, it is used to monitor the patient’s motor, verbal, and eye-opening responses. The pa-tient’s best responses to predetermined stimuli are recorded (see Chart 63-4). Each response is scored (the greater the num-ber the better the functioning), and the sum of these scores gives an indication of the severity of coma and a prediction of possible outcome. The lowest score is 3 (least responsive); the highest is 15 (most responsive). A score of 8 or less is generally accepted as indicating a severe head injury (Teasdale & Jennett, 1974).

Vital Signs

Although a change in LOC is the most sensitive neurologic

indi-cation of deterioration of the patient’s condition, vital signs are

monitored at frequent intervals also to assess the intracranial sta-tus. Table

63-1 depicts the general assessment parameters for the patient with a head

injury.

Signs of increasing ICP

include slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia), increasing systolic blood

pressure, and widening pulse pressure. As brain compression increases,

respirations be-come rapid, the blood pressure may decrease, and the pulse

slows further. This is an ominous development, as is a rapid fluctuation of

vital signs (March, 2000). A rapid rise in body temperature is regarded as

unfavorable because hyperthermia increases the meta-bolic demands of the brain

and may indicate brain stem damage, a poor prognostic sign. The temperature is

maintained at less than 38°C (100.4°F). Tachycardia and arterial hypotension may indicate

that bleeding is occurring elsewhere in the body.

Motor Function

Motor function is

assessed frequently by observing spontaneous movements, asking the patient to

raise and lower the extremities, and comparing the strength and equality of the

hand grasp and pedal push at periodic intervals. To assess the hand grasp, the

nurse instructs the patient to squeeze the examiner’s fingers tightly. The

nurse assesses lower extremity motor strength (pedal push) by placing the hands

on the soles of the patient’s feet and asking the patient to push down against

the examiner’s hands. The presence or absence of spontaneous movement of each

extremity is also noted, and speech and eye signs are assessed.

If the patient does not

demonstrate spontaneous movement, responses to painful stimuli are assessed.

Motor response to pain is assessed by applying a central stimulus, such as

pinching the pectoralis major muscle, to determine the patient’s best response.

Peripheral stimulation may provide inaccurate assessment data because it may

result in a reflex movement rather than a voluntary motor response. Abnormal

responses (lack of motor response; extension responses) are associated with a

poorer prognosis.

Other Neurologic Signs

In addition to the patient’s spontaneous eye opening

evaluated with the Glasgow Coma Scale, the size and equality of the pupils and

their reaction to light are assessed. A unilaterally dilated and poorly

responding pupil may indicate a developing hematoma, with subsequent pressure

on the third cranial nerve due to shift-ing of the brain. If both pupils become

fixed and dilated, this in-dicates overwhelming injury and intrinsic damage to

the upper brain stem and is a poor prognostic sign.

The patient with a head

injury may develop focal nerve palsies such as anosmia (lack of sense of smell)

or eye movement abnor-malities and focal neurologic deficits such as aphasia,

memory deficits, and post-traumatic seizures or epilepsy. Patients may be left with

residual organic psychological deficits (impulsiveness, emotional lability, or

uninhibited, aggressive behaviors) and, as a consequence of the impairment,

lack insight into their emotional responses (Davis, 2000).

MAINTAINING THE AIRWAY

One of the most

important nursing goals in the management of the patient with a head injury is

to establish and maintain an ad-equate airway. The brain is extremely sensitive

to hypoxia, and a neurologic deficit can worsen if the patient is hypoxic.

Therapy is directed toward maintaining optimal oxygenation to preserve cerebral

function. An obstructed airway causes CO2

retention and hypoventilation, which can produce cerebral vessel dilation and

increased ICP.

Interventions to ensure an adequate exchange of air and

include the following:

·

Keep the unconscious patient

in a position that facilitates drainage of oral secretions, with the head of

the bed elevated about 30 degrees to decrease intracranial venous pressure

(Bader & Palmer, 2000).

·

Establish effective suctioning

procedures (pulmonary secre-tions produce coughing and straining, which

increase ICP).

·

Guard against aspiration and

respiratory insufficiency.

·

Closely monitor arterial blood

gas values to assess the ade-quacy of ventilation. The goal is to keep blood gas

values within the normal range to ensure adequate cerebral blood flow.

·

Monitor the patient who is

receiving mechanical ventilation.

·

Monitor for pulmonary

complications such as acute respi-ratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and pneumonia

(Munro, 2000).

MONITORING FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE BALANCE

Brain damage can produce metabolic and hormonal

dysfunctions. The monitoring of serum electrolyte levels is important,

especially in patients receiving osmotic diuretics, those with inappropriate

antidiuretic hormone secretion, and those with post-traumatic diabetes

insipidus.

Serial studies of blood

and urine electrolytes and osmolality are carried out because head injuries may

be accompanied by dis-orders of sodium regulation. Hyponatremia is common

follow-ing head injury due to shifts in extracellular fluid, electrolytes, and

volume. Hyperglycemia, for example, may cause an increase in extracellular

fluid that lowers sodium (Hickey, 2003). Hyper-natremia may also occur due to

sodium retention that may last several days, followed by sodium diuresis.

Increasing lethargy, confusion, and seizures may be due to electrolyte

imbalance.

Endocrine function is evaluated by monitoring serum

elec-trolytes, blood glucose values, and intake and output. Urine is tested

regularly for acetone. A record of daily weights is main-tained, especially if

the patient has hypothalamic involvement and is at risk for the development of

diabetes insipidus.

PROMOTING ADEQUATE NUTRITION

Head injury results in metabolic changes that increase calorie

consumption and nitrogen excretion (Donaldson et al., 2000). There is an

increased demand for protein. As soon as possible, nu-trition should be

provided. Early initiation of nutritional therapy has been shown to improve

outcomes in head-injured patients (Bader & Palmer, 2000). Parenteral

nutrition via a central line or enteral feedings administered via a nasogastric

or nasojejunal feeding tube may be used. If there is discharge of CSF from the

nose (CSF rhinorrhea), an oral feeding tube should be inserted in place of a

nasal tube.

Laboratory values should

be monitored closely in patients re-ceiving parenteral nutrition. Elevating the

head of the bed and as-pirating the enteral tube for evidence of residual

feeding before administering additional feedings can help prevent distention,

re-gurgitation, and aspiration. A continuous-drip infusion or pump may be used

to regulate the feeding. Enteral or par-enteral feedings are usually continued

until the swallowing reflex returns and the patient can meet caloric

requirements orally.

PREVENTING INJURY

As the patient emerges

from coma, there is often a period of lethargy and stupor followed by a period

of agitation. Each phase is variable and depends on the individual, the

location of the in-jury, the depth and duration of coma, and the patient’s age.

The patient emerging from a coma may become increasingly agitated toward the

end of the day. Restlessness may be due to hypoxia, fever, pain, or a full

bladder. It may indicate injury to the brain but may also be a sign that the

patient is regaining consciousness. (Some restlessness may be beneficial

because the lungs and extremities are exercised.) Agitation may also be due to

discomfort from catheters, intravenous lines, restraints, and repeated

neurologic checks. Alter-natives to restraints must be used whenever possible.

Strategies to prevent

injury include the following:

·

Assess the patient to ensure

that oxygenation is adequate and the bladder is not distended. Check dressings

and casts for constriction.

·

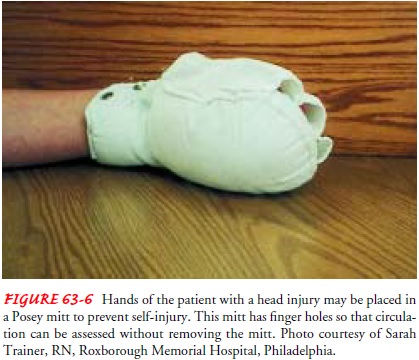

To protect the patient from

self-injury and dislodging of tubes, use padded side rails or wrap the

patient’s hands in mitts (Fig. 63-6). Restraints are avoided because straining

against them can increase ICP or cause other injury. En-closed or floor-level

specialty beds may be indicated.

·

Avoid using opioids as a means

of controlling restlessness because these medications depress respiration,

constrict the pupils, and alter responsiveness.

·

Minimize environmental stimuli

by keeping the room quiet, limiting visitors, speaking calmly, and providing

fre-quent orientation information (eg, explaining where the pa-tient is and

what is being done).

·

Provide adequate lighting to

prevent visual hallucinations.

·

Minimize disruption of the

patient’s sleep/wake cycles.

·

Lubricate the skin with oil or

emollient lotion to prevent irritation due to rubbing against the sheet.

·

If incontinence occurs,

consider use of an external sheath catheter on a male patient. Because

prolonged use of an in-dwelling catheter inevitably produces infection, the

patient may be placed on an intermittent catheterization schedule.

MAINTAINING BODY TEMPERATURE

An increase in body temperature in the head-injured

patient can be the result of damage to the hypothalamus, cerebral irritation

from hemorrhage, or infection. The nurse monitors the patient’s temperature

every 4 hours. If the temperature rises, efforts are undertaken to identify the

cause and to control it using acetamin-ophen and cooling blankets as prescribed

(Bader & Palmer, 2000). Cooling blankets should be used with caution so as

not to induce shivering, which increases ICP. If infection is suspected,

potential sites of infection are cultured and antibiotics are pre-scribed and

administered.

MAINTAINING SKIN INTEGRITY

Patients with traumatic head injury often require

assistance in turning and positioning because of immobility or

unconscious-ness. Prolonged pressure on the tissues will decrease circulation

and lead to tissue necrosis. Potential areas of breakdown need to be identified

early to avoid the development of pressure ulcers. Specific nursing measures

include the following:

·

Assess all body surfaces and

document skin integrity at least every 8 hours.

·

Turn and reposition the

patient every 2 hours.

·

Provide skin care every 4

hours.

·

Assist patient to get out of

bed to a chair three times a day if physically able.

IMPROVING COGNITIVE FUNCTIONING

Although many patients with head injury survive because

of re-suscitative and supportive technology, they frequently have sig-nificant

cognitive sequelae that may not be detected during the acute phase of injury.

Cognitive impairment includes memory deficits, decreased ability to focus and

sustain attention to a task (distractibility), reduced ability to process

information, and slow-ness in thinking, perceiving, communicating, reading, and

writ-ing. Psychiatric or emotional problems develop in as many as 44% of

patients with head injury (van Reekum et al., 2000). Re-sulting psychosocial,

behavioral, emotional, and cognitive im-pairments are devastating to the family

as well as to the patient (Davis, 2000; Perlesz, Kinsella, & Crowe, 1999).

These problems require collaboration among many

disciplines (Bader & Palmer, 2000). A neuropsychologist (specialist in

eval-uating and treating cognitive problems) plans a program and ini-tiates

therapy or counseling to help the patient reach maximal potential. Cognitive

rehabilitation activities help the patient to devise new problem-solving

strategies. The retraining is carried out over an extended period and may

include the use of sensory stimulation and reinforcement, behavior

modification, reality orientation, computer-training programs, and video games.

As-sistance from many disciplines is necessary during this phase of recovery.

Even if intellectual ability does not improve, social and behavioral abilities

may.

The patient recovering

from a brain injury may experience fluctuations in the level of cognitive

function, with orientation, attention, and memory frequently affected. When

pushed to a level greater than the impaired cortical functioning allows, the

patientmay show symptoms of fatigue, anger, and stress (headache, dizziness).

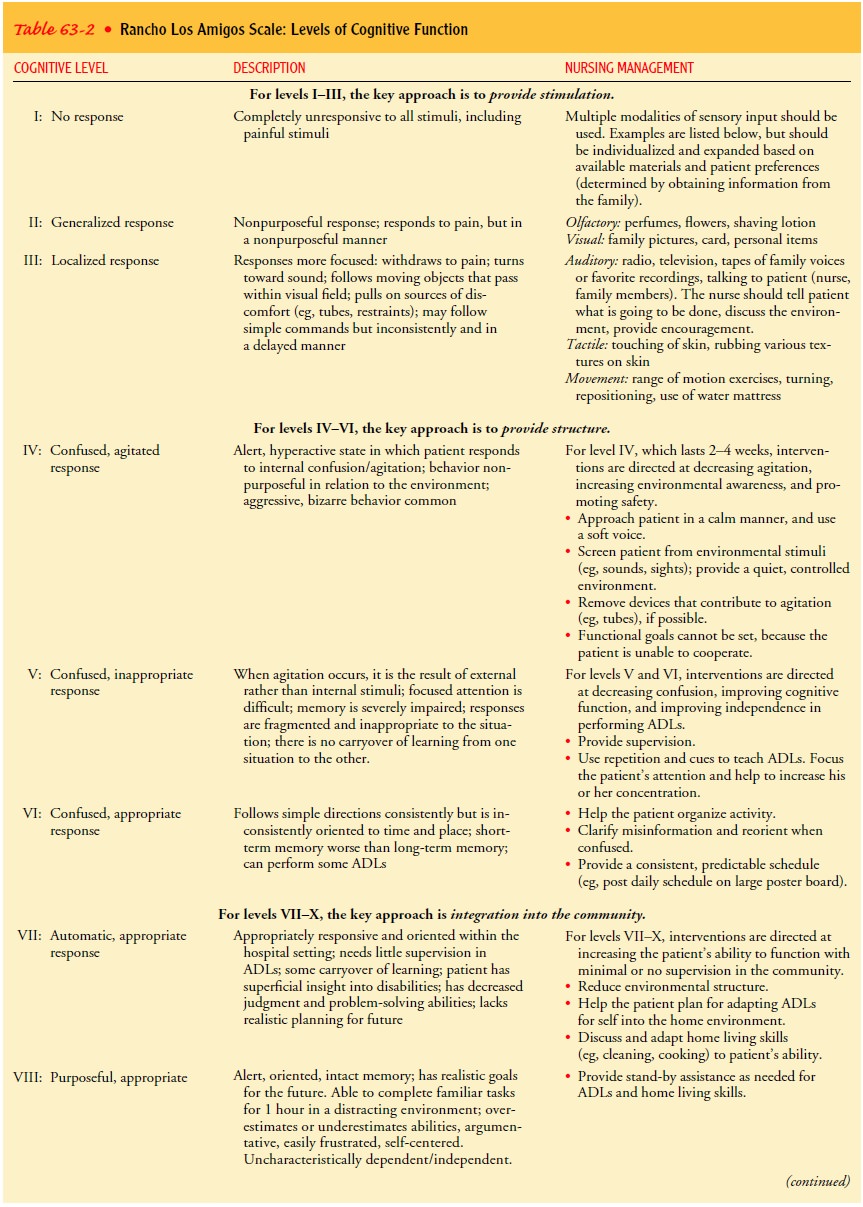

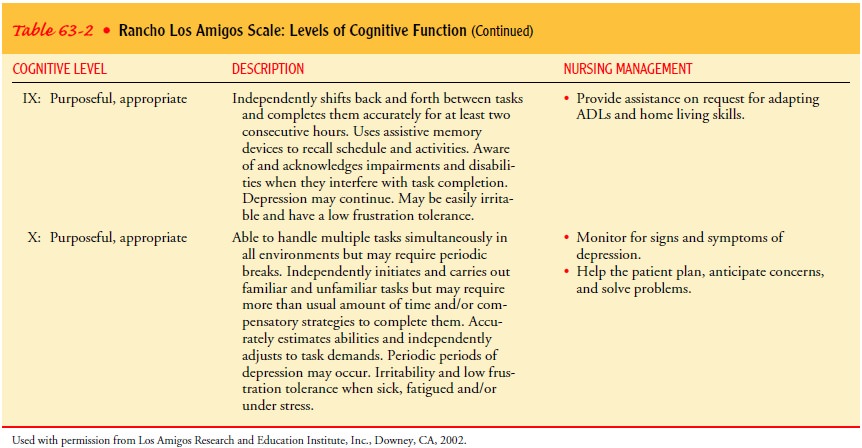

The Rancho Los Amigos Level of Cognitive Function is a scale frequently used to

assess cognitive function and evalu-ate ongoing recovery from head injury.

Nursing management and a description of each level are included in Table 63-2.

PREVENTING SLEEP PATTERN DISTURBANCE

Patients who require

frequent monitoring of neurologic status may experience sleep deprivation. They

are awakened hourly to assess LOC and as a result are deprived of long periods

of sleep and rest. In an effort to allow the patient longer times of

uninter-rupted sleep and rest, the nurse can group nursing care activities so

that the patient is disturbed less frequently. Environmental noise is decreased

and the room lights are dimmed. Back rubs and other activities to increase

comfort can assist in promoting sleep and rest.

SUPPORTING FAMILY COPING

Having a loved one

sustain a serious head injury can produce a great deal of prolonged stress in

the family. This stress can result from the patient’s physical and emotional

deficits, the unpre-dictable outcome, and altered family relationships.

Families report difficulties in coping with changes in the patient’s temperament,

behavior, and personality. Such changes are associated with dis-ruption in

family cohesion, loss of leisure pursuits, and loss of work capacity, as well

as social isolation of the caretaker. The family may experience anger, grief,

guilt, and denial in recurring cycles (Perlesz et al., 1999).

To promote effective

coping, the nurse can ask the family how the patient is different at this time:

What has been lost? What is most difficult about coping with this situation?

Helpful inter-ventions include providing family members with accurate and

honest information and encouraging them to continue to set well-defined,

mutual, short-term goals. Family counseling helps address the family members’

overwhelming feelings of loss and helplessness and gives them guidance for the

management of in-appropriate behaviors. Support groups help the family members

share problems, develop insight, gain information, network, and gain assistance

in maintaining realistic expectations and hope.

The National Head Injury

Foundation serves as a clearing-house for information and resources for

patients with head in-juries and their families, including specific information

on coma, rehabilitation, behavioral consequences of head injury, and fam-ily

issues. This organization can provide names of facilities and professionals who

work with patients with head injuries and can assist families in organizing

local support groups.

Many patients with

severe head injury die of their injuries, and many of those who survive

experience long-term problems that prevent them from resuming their previous

roles and functions. During the most acute phase of injury, family members need

sup-port and facts from the health care team.

Many individuals with

severe head injuries that result in brain death are young and otherwise healthy

and are therefore consid-ered for organ donation. Family members of patients

with such injuries need support during this extremely stressful time and

as-sistance in making decisions to end life support and permit do-nation of

organs. They need to know that the brain-dead patient whose respiratory and

cardiovascular systems are maintained through life support is not going to

survive and that the severe head injury, not the removal of the patient’s

organs or the re-moval of life support, is the cause of patient’s death.

Bereavement counselors and members of the organ procurement team areoften very

helpful to family members in making decisions about organ donation and in

helping them cope with stress.

MONITORING AND MANAGING POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Decreased Cerebral Perfusion

Maintenance of adequate

CPP is important to prevent serious complications of head injury due to

decreased cerebral perfusion (Bader & Palmer, 2000; March, 2000). Adequate

CPP is greater than 70 mm Hg. Any decrease in this pressure can impair cerebral

perfusion and cause brain hypoxia and ischemia, leading to per-manent damage.

Therapy (eg, elevation of the head of the bed and increased intravenous fluids)

is directed toward decreasing cerebral edema and increasing venous outflow from

the brain. Systemic hypotension, which causes vasoconstriction and a

signif-icant decrease in CPP, is treated with increased intravenous fluids.

Cerebral Edema and Herniation

The patient with a head

injury is at risk for additional complica-tions such as increased ICP and brain

stem herniation. Cerebral edema is the most common cause of increased ICP in

the patient with a head injury, with the swelling peaking approximately 48 to

72 hours after injury. Bleeding also may increase the volume of contents within

the rigid closed compartment of the skull, causing increased ICP and herniation

of the brain stem and re-sulting in irreversible brain anoxia and brain death.

Impaired Oxygenation and Ventilation

Impaired oxygen and

ventilation may necessitate mechanical ven-tilatory support. The patient must

be monitored for a patent air-way, altered breathing patterns, and hypoxemia

and pneumonia. Interventions may include endotracheal intubation, mechanical

ventilation, and positive end-expiratory pressure.

Impaired Fluid, Electrolyte, and Nutritional Balance

Fluid, electrolyte, and

nutritional imbalances are common in the patient with a head injury. Common

imbalances may include hyponatremia, which is often associated with the

syndrome of in-appropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (see Chaps. 14 and

42), hypokalemia, and hyperglycemia (Hickey, 2003). Modifica-tions in fluid

intake with tube feedings or intravenous fluids may be necessary to treat these

imbalances. Insulin administra-tion may be prescribed to treat hyperglycemia.

Undernutrition is also a

common problem in response to the increased metabolic needs associated with

severe head injury. If the patient cannot eat, enteral feedings or parenteral

nutrition may be initiated within 24 hours of injury to provide adequate

calories and nutrients.

Post-traumatic Seizures

Patients with head injury are at an increased risk for post-traumatic seizures. Post-traumatic seizures are classified as im-mediate (within 24 hours of injury), early (within 1 to 7 days of injury), or late (more than 7 days following injury) (Kado & Patel, 1999). Seizure prophylaxis refers to the practice of administering antiseizure medications to patients following head injury to pre-vent seizures. It is important to prevent post-traumatic seizures, especially in the immediate and early phase of recovery, as seizures may increase ICP and decrease oxygenation.

Many antiseizure medications impair cognitive performance, prolonging the dura-tion of rehabilitation. Therefore, it is important to weigh the overall benefit of these medications against their side effects. Currently, there is no conclusive evidence that long-term antiseizure prophylaxis improves outcomes in patients with head in-jury. Research evidence supports the use of prophylactic antiseizure agents to prevent immediate and early seizure after head injury, but not for prevention of late seizures (Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care, 2000).

Nurses must assess patients carefully for the development

of post-traumatic seizures. Risk factors that increase the likelihood of

seizures are brain contusion with subdural hematoma, skull fracture, loss of

consciousness or amnesia of 1 day or more, and age over 65 years (Annegers

& Coan, 2000).

Other complications

after traumatic head injury include sys-temic infections (pneumonia, urinary

tract infection [UTI], sep-ticemia), neurosurgical infections (wound infection,

osteomyelitis, meningitis, ventriculitis, brain abscess), and heterotrophic

ossifi-cation (painful bone overgrowth in weight-bearing joints).

PROMOTING HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED CARE

Teaching Patients Self-Care

Teaching early in the course of head injury often focuses

on re-inforcing information given to the family about the patient’s con-dition

and prognosis. As the patient’s status and expected outcome change over time,

family teaching may focus on interpretation and explanation of changes in the

patient’s physical and psycho-logical responses.

If the patient’s physical status allows him or her to be

dis-charged home, the patient and family are instructed about limi-tations that

can be expected and complications that may occur. Monitoring for complications

that merit contacting the neuro-surgeon is explained to the patient and family

verbally and in writing. Depending on the patient’s prognosis and physical and

cognitive status, the patient may be included in teaching about self-care

management strategies.

Because of the risk for post-traumatic seizures,

antiseizure med-ications may be prescribed for 1 to 2 years after injury. The

patient and family require instruction about the side effects of these

med-ications and about the importance of continuing to take them as prescribed.

Continuing Care

Rehabilitation of the

patient with a head injury begins at the time of injury and extends into the

home and community. Depending on the degree of brain damage, the patient may be

referred to a rehabilitation setting that specializes in cognitive

restructuring of the brain-injured patient. The patient is encouraged to continue

the rehabilitation program after discharge because improvement in status may

continue 3 or more years after injury. Changes in the head-injured patient and

the effects of long-term rehabilitation on the family and their coping

abilities need frequent assessment. Teaching and continued support of the

patient and family are es-sential as their needs and the patient’s status

change. Teaching points to address with the family of the head-injured patient

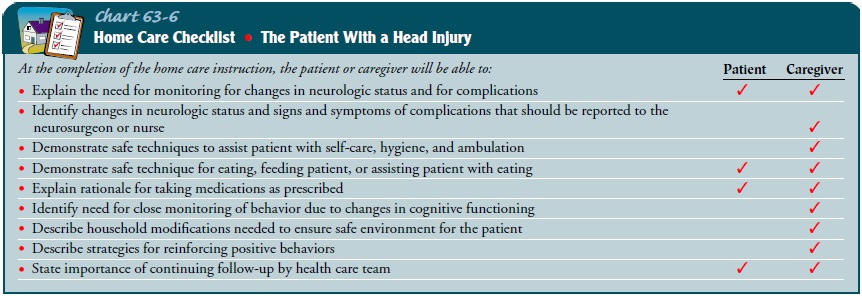

who is about to return home are described in Chart 63-6.

Depending on his or her status, the patient is encouraged

to return to normal activities gradually. Referral to support groups and the

National Head Injury Foundation may be warranted.

During the acute and rehabilitation phase of care, the

focus of teaching is on obvious needs, issues, and deficits. The nurse needs to

remind patients and family members of the need for continuing health promotion

and screening practices following these initial phases. Patients who have not

been involved in these practices in the past are educated about their

importance and are referred to appropriate health care providers.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected patient outcomes may include:

1) Attains

or maintains effective airway clearance, ventilation, and brain oxygenation

a) Achieves

normal blood gas values and has normal breath sounds on auscultation

b) Mobilizes and clears secretions

2) Achieves

satisfactory fluid and electrolyte balance

a) Demonstrates

serum electrolytes within normal range

b) Has

no clinical signs of dehydration or overhydration

3) Attains

adequate nutritional status

a) Has

less than 50 mL of aspirate in stomach before each tube feeding

b) Is

free of gastric distention and vomiting

c) Shows

minimal weight loss

4) Avoids

injury

a) Shows

lessening agitation and restlessness

b) Is

oriented to time, place, and person

5) Does

not have a fever

6) Demonstrates

intact skin integrity

a) Exhibits

no redness or breaks in skin integrity

b) Exhibits

no pressure ulcers

7) Shows

improvement in cognitive function and improved memory

8) Demonstrates

normal sleep/wake cycle

9) Demonstrates

absence of complications

a) Exhibits

normal ICP, normal vital signs and body temperature, and increasing orientation

to time, place, and person

b) Demonstrates

reduced ICP

10) Patient

experiences no post-traumatic seizures

a) Takes

antiseizure medications as prescribed

b) Identifies

side effects/adverse effects of antiseizure medications

11) Demonstrate

adaptive coping mechanisms for family members

a) Join

support group

b) Share

feelings with appropriate health care personnel

c) Make

end-of-life decisions, if needed

12) Participate

in rehabilitation process as indicated for pa-tient and family members

a) Take

active role in identifying rehabilitation goals and participating in

recommended patient care activities

b) Prepare

for discharge of patient

Related Topics