Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Trauma

Head Injuries

Head

Injuries

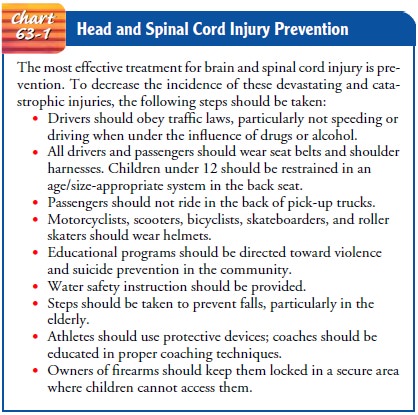

Head injury is a broad

classification that includes injury to the scalp,skull, or brain. It is the

most common cause of death from trauma in the United States. Approximately 1

million people receive treatment for head injuries every year. Of these,

230,000 are hospitalized, 80,000 have permanent disabilities, and 50,000 people

die (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2001). Traumatic brain

injury is the most serious form of head injury.The most common causes of

traumatic brain injury are motor vehicle crashes, violence, and falls. Groups

at highest risk for traumatic brain injury are persons age 15 to 24 years and

males, who suffer traumatic brain injury at a rate almost twice that of

females. The very young (under 5) and the very old (over 75) are also at

increased risk. It is estimated that 5.3 million Americans today are living

with a disability as a result of a traumatic brain injury (CDC, 2001). The best

approach to head injury is prevention (Chart 63-1).

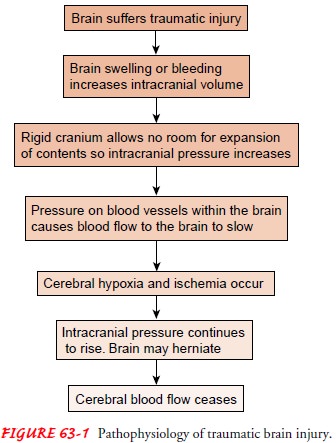

Pathophysiology

Research suggests that not all brain damage occurs at the moment of impact. Damage to the brain from traumatic injury takes two forms: primary injury and secondary injury. Primary injury is the initial damage to the brain that results from the traumatic event. This may include contusions, lacerations, and torn blood vessels from impact, acceleration/deceleration, or foreign object penetration (Blank-Reid & Reid, 2000; Porth, 2002). Secondary injury evolves over the ensuing hours and days after the initial injury and is due primarily to brain swelling or ongoing bleeding.An injured brain is different from other injured body areas due to its unique characteristics.

It resides within the skull, which is a rigid closed compartment

(Bader & Palmer, 2000). Unlike an injured ankle, in which the covering skin

expands with swelling, the confines of the skull do not allow for the expansion

of cranial contents. Thus, any bleeding or swelling within the skull increases

the volume of contents within a container of fixed size and so can cause

increased intracranial pressure (ICP). If the increased pressure is high

enough, it can cause a downward or lateral displacement of the brain through or

against the rigid structures of the skull. This causes restriction of blood

flow to the brain, decreasing oxygen delivery and waste removal. Cells within

the brain become anoxic and cannot metabolize properly, producing ischemia,

infarction, irreversible brain damage, and eventually brain death (Fig. 63-1).

SCALP INJURY

Isolated scalp trauma is generally classified as a minor head injury. Because its many blood vessels constrict poorly, the scalp bleeds profusely when injured.

Trauma may result in an abrasion

(brush wound), contusion, laceration, or hematoma beneath the layers of tissue

of the scalp (subgaleal hematoma). Large avulsions of the scalp may be

potentially life-threatening and are true emergen-cies. Diagnosis of any scalp

injury is based on physical examina-tion, inspection, and palpation. Scalp

wounds are potential portals of entry of organisms that cause intracranial

infections. There-fore, the area is irrigated before the laceration is sutured

to remove foreign material and to reduce the risk for infection. Subgaleal

hematomas (hematomas below the outer covering of the skull) usually absorb on

their own and do not require any specific treatment.

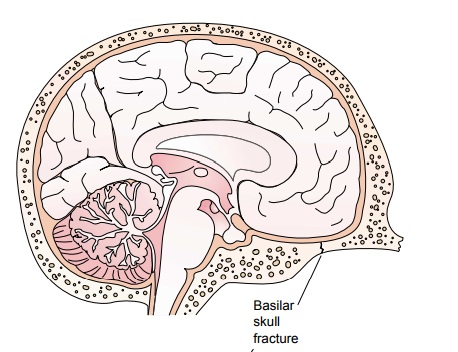

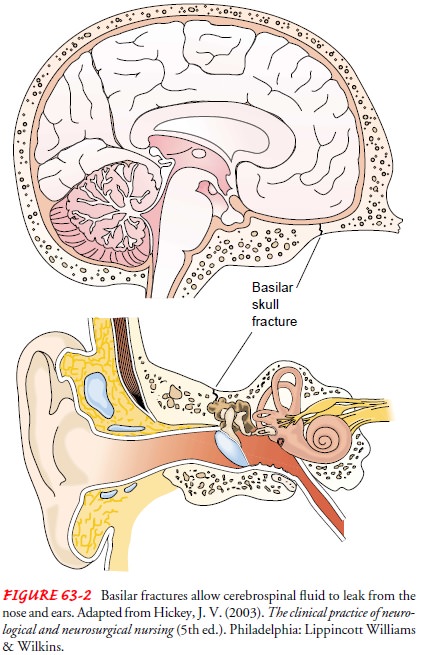

SKULL FRACTURES

A skull fracture is a break in the continuity of the

skull caused by forceful trauma. It may occur with or without damage to the

brain. Skull fractures are classified as linear, comminuted, de-pressed, or

basilar. A fracture may be open, indicating a scalp laceration or tear in the

dura (eg, from a bullet or an ice pick), or closed, in which the dura is intact

(Fig. 63-2).

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms, apart from those of the local injury,

depend on the severity and the distribution of brain injury. Persistent,

local-ized pain usually suggests that a fracture is present. Fractures of the

cranial vault may or may not produce swelling in the region of the fracture;

therefore, an x-ray is needed for diagnosis.

Fractures of the base of the skull tend to traverse the paranasal sinus of the frontal bone or the middle ear located in the tempo-ral bone (see Fig. 63-2). Thus, they frequently produce hemor-rhage from the nose, pharynx, or ears, and blood may appear under the conjunctiva. An area of ecchymosis (bruising) may be seen over the mastoid (Battle’s sign).

Basal skull

fractures are suspected when cerebrospinal fluid escapes from the ears (CSF

otorrhea) and the nose (CSF rhinorrhea). A halo sign (a blood stain surrounded

by a yellowish stain) may be seen on bed linens or the head dressing and is

highly suggestive of a CSF leak. Drainage of CSF is a serious problem because

meningeal infec-tion can occur if organisms gain access to the cranial contents

through the nose, ear, or sinus through a tear in the dura. Bloody CSF suggests

a brain laceration or contusion.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Although a rapid physical examination and evaluation of

neuro-logic status detect the more obvious brain injuries, a computed

tomography (CT) scan can detect less apparent abnormalities by the degree to

which the soft tissue absorbs the x-rays. It is a fast, accurate, and safe

diagnostic study that shows the presence, nature, location, and extent of acute

lesions. It is also helpful in the on-going management of patients with head

injury as it can dis-close cerebral edema, contusion, intracerebral or

extracerebral hematoma, subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage, and late

changes (infarction, hydrocephalus). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used

to evaluate patients with head injury when a more accurate picture of the

anatomic nature of the injury is warranted and when the patient is stable

enough to undergo this longer diagnostic study.

Cerebral angiography may also be used; it identifies

supra-tentorial, extracerebral, and intracerebral hematomas and cere-bral

contusions. Lateral and anteroposterior views of the skull are obtained.

Medical Management

Nondepressed skull

fractures generally do not require surgical treatment; however, close

observation of the patient is essential. Nursing personnel may observe the

patient in the hospital, but if no underlying brain injury is present, the

patient may be allowed to return home. If the patient is discharged home,

specific in-structions must be given to

the family. Many depressed skull fractures are managed conserva-tively; only

contaminated or deforming fractures require surgery.

If surgery is necessary,

the scalp is shaved and cleansed with copious amounts of saline to remove

debris. The fracture is then exposed. After the skull fragments are elevated,

the area is débrided. Large defects can be repaired immediately with bone or

artificial grafts; if significant cerebral edema is present, repair of the

defect can be delayed for 3 to 6 months. Penetrating wounds require surgical

débridement to remove foreign bodies and devitalized brain tissue and to

control hemorrhage (Blank-Reid & Reid, 2000). Antibiotic treatment is

instituted immediately, and blood component therapy is administered if

indicated.

As stated previously, fractures of the base of the skull

are se-rious because they are usually open (involving the paranasal sinuses or

middle or external ear) and result in CSF leakage. The nasopharynx and the

external ear should be kept clean. Usually a piece of sterile cotton is placed

loosely in the ear, or a sterile cotton pad may be taped loosely under the nose

or against the ear to collect the draining fluid. The patient who is conscious

is cau-tioned against sneezing or blowing the nose. The head is elevated 30

degrees to reduce ICP and promote spontaneous closure of the leak (Sullivan,

2000), although some neurosurgeons prefer that the bed be kept flat. Persistent

CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea usually requires surgical intervention.

Related Topics