Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Neurologic Trauma

Brain Injury

Brain

Injury

The most important consideration in any head injury is

whether or not the brain is injured. Even seemingly minor injury can cause

significant brain damage secondary to obstructed blood flow and decreased

tissue perfusion. The brain cannot store oxygen and glucose to any significant

degree. Because the cerebral cells need an uninterrupted blood supply to obtain

these nutrients, irre-versible brain damage and cell death occur when the blood

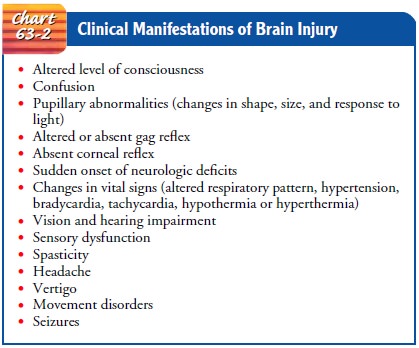

sup-ply is interrupted for even a few minutes. Clinical manifestations of brain injury are listed in Chart 63-2. Closed (blunt) braininjury occurs when

the head accelerates and then rapidly decel-erates or collides with another

object (eg, a wall or dashboard of a car) and brain tissue is damaged, but

there is no opening through the skull and dura. Open brain injury occurs when an object penetrates the skull,

enters the brain, and damages the soft brain tissue in its path (penetrating

injury), or when blunt trauma to the head is so severe that it opens the scalp,

skull, and dura to expose the brain.

Concussion

A cerebral concussion after head injury is a temporary loss of neurologic function with no apparent structural damage. A con-cussion generally involves a period of unconsciousness lasting from a few seconds to a few minutes.

The jarring of the

brain may be so slight as to cause only dizziness and spots before the eyes

(“seeing stars”), or it may be severe enough to cause complete loss of

consciousness for a time. If the brain tissue in the frontal lobe is affected,

the patient may exhibit bizarre irrational behavior, whereas involvement of the

temporal lobe can produce temporary amnesia or disorientation.

The patient may be

hospitalized overnight for observation or discharged from the hospital in a

relatively short time after a con-cussion. Treatment involves observing the

patient for headache, dizziness, lethargy, irritability, and anxiety. The

occurrence of these symptoms after injury is referred to as postconcussion

syndrome. Giving the patient information, explanations, and encouragement may

reduce some of the problems of postconcussion syndrome. The patient is advised

to resume normal activities slowly, and the family is instructed to observe for

the following signs and symp-toms and to notify the physician or clinic (or

bring the patient to the emergency department) if they occur:

·

Difficulty in awakening

·

Difficulty in speaking

·

Confusion

·

Severe headache

·

Vomiting

·

Weakness of one side of the

body

A concussion was once thought of as a minor head injury

without significant sequelae. However, studies have demonstrated that there are

often disturbing and sometimes residual effects, in-cluding headache, lethargy,

personality and behavior changes, attention deficits, difficulty with memory,

and disruption in work habits (Ponsford et al., 1999).

Gerontologic Considerations

Elderly patients must be

assessed very carefully. Even given similar mechanisms of injury, an elderly

person will often suffer more severe injury than a young person and will often

recover more slowly and with more complications (Perdue et al., 1998). The

elderly patient with confusion or behavioral disturbances should be assessed

for head injury, because unrecognized “minor” head trauma may account for

behavioral and confusional episodes in some elderly people (Walshaw, 2000). A

misdiagnosed or un-treated episode of confusion in an elderly patient may

result in long-term disability that might have been avoided if the injury had

been detected and treated promptly.

Contusion

Cerebral contusion is a more severe injury in

which the brain is bruised, with possible surface hemorrhage. The patient is

un-conscious for more than a few seconds or minutes. Clinical signs and

symptoms depend on the size of the contusion and the amount of associated

cerebral edema. The patient may lie motionless, with a faint pulse, shallow

respirations, and cool, pale skin. Often there is involuntary evacuation of the

bowels and the bladder. The patient may be aroused with effort but soon slips

back into unconsciousness. The blood pressure and the temperature are

subnormal, and the picture is somewhat similar to that of shock.

In general, patients with severe brain injury who have

abnor-mal motor function, abnormal eye movements, and elevated ICP have poor

outcomes—that is, brain damage, disability, or death. Conversely, the patient

may recover consciousness but pass into a stage of cerebral irritability. In

this stage, the patient is conscious and easily disturbed by any form of

stimulation such as noises, light, and voices; he or she may become hyperactive

at times. Gradually, the pulse, respirations, temperature, and other body

functions return to normal, but full recovery can be delayed for months.

Residual headache and vertigo are common, and im-paired mental function or

seizures may occur as a result of irreparable cerebral damage.

Diffuse Axonal Injury

Diffuse axonal injury involves widespread damage to axons

in the cerebral hemispheres, corpus callosum, and brain stem. It can be seen in

mild, moderate, or severe head trauma and results in axonal swelling and

disconnection (Porth, 2002). Clinically, with severe injury, the patient has no

lucid intervals and experiences imme-diate coma, decorticate and decerebrate

posturing, and global cerebral edema. Diagnosis is made by clinical signs in

conjunction with a CT scan or MRI. Recovery depends on the severity of the

axonal injury.

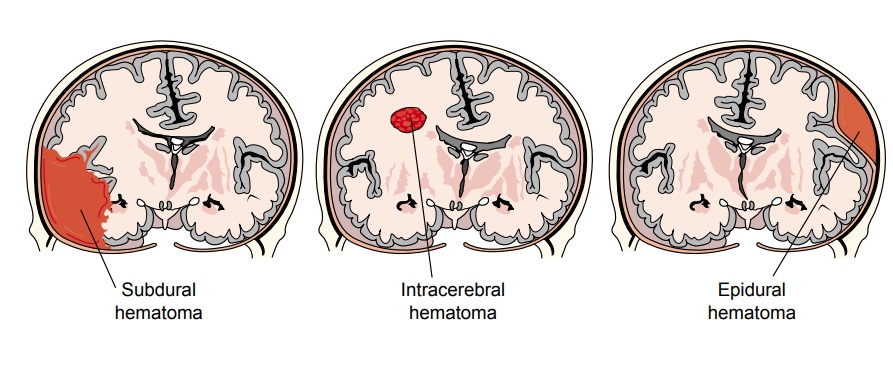

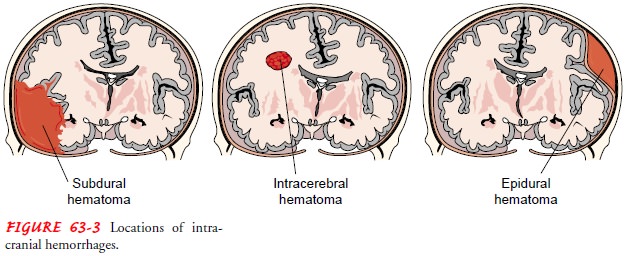

Intracranial Hemorrhage

Hematomas (collections

of blood) that develop within the cra-nial vault are the most serious brain

injuries (Porth, 2002). A hematoma may be epidural (above the dura), subdural

(below the dura), or intracerebral (within the brain) (Fig. 63-3). Major

symptoms are frequently delayed until the hematoma is large enough to cause

distortion of the brain and increased ICP. The signs and symptoms of cerebral

ischemia resulting from the compression by a hematoma are variable and depend

on the speed with which vital areas are affected and the area that is injured.

In general, a rapidly developing hematoma, even if small, may be fatal, whereas

a larger but slowly developing collection of blood may allow compensation for

increases in ICP.

EPIDURAL HEMATOMA (EXTRADURAL HEMATOMA OR HEMORRHAGE)

After a head injury, blood may collect in the epidural

(extradural) space between the skull and the dura. This can result from a skull

fracture that causes a rupture or laceration of the middle meningeal artery,

the artery that runs between the dura and the skull infe-rior to a thin portion

of temporal bone. Hemorrhage from this artery causes rapid pressure on the

brain.

Symptoms are caused by the expanding hematoma. Usually,

there is a momentary loss of consciousness at the time of injury, followed by an

interval of apparent recovery (lucid interval). Although the lucid interval is

considered a classic characteristic of an epidural hematoma, no lucid interval

has been reported in many patients with this lesion (Servadei, 1997), and thus

it should not be considered a critical defining criterion. During the lucid

interval, compensation for the expanding hematoma takes place by rapid

absorption of CSF and decreased intravascular volume, both of which help

maintain a normal ICP. When these mecha-nisms can no longer compensate, even a

small increase in the volume of the blood clot produces a marked elevation in

ICP. Then, often suddenly, signs of compression appear (usually dete-rioration

of consciousness and signs of focal neurologic deficits such as dilation and

fixation of a pupil or paralysis of an extremity), and the patient deteriorates

rapidly.

An epidural hematoma is considered an extreme emergency;

marked neurologic deficit or even respiratory arrest can occur within minutes.

Treatment consists of making openings through the skull (burr holes) to

decrease ICP emergently, remove the clot, and control the bleeding. A

craniotomy may be required to remove the clot and control the bleeding. A drain

is usually in-serted after creation of burr holes or a craniotomy to prevent

reaccumulation of blood.

SUBDURAL HEMATOMA

A subdural hematoma is a collection of blood between the dura and the brain, a space normally occupied by a thin cushion of fluid. The most common cause of subdural hematoma is trauma, but it may also occur from coagulopathies or rupture of an aneurysm. A subdural hemorrhage is more frequently venous in origin and is due to the rupture of small vessels that bridge the subdural space. A subdural hematoma may be acute, subacute, or chronic, depending on the size of the involved vessel and the amount of bleeding present.

Acute and Subacute Subdural Hematoma.

Acute subdural

hema-tomas are associated with major head injury involving contusion or

laceration. Clinical symptoms develop over 24 to 48 hours. Signs and symptoms

include changes in the level of consciousness (LOC), pupillary signs, and

hemiparesis. There may be minor or even no symptoms with small collections of

blood. Coma, in-creasing blood pressure, decreasing heart rate, and slowing

respi-ratory rate are all signs of a rapidly expanding mass requiring immediate

intervention.

Subacute subdural hematomas are the result of less severe

con-tusions and head trauma. Clinical manifestations usually appear between 48

hours and 2 weeks after the injury. Signs and symp-toms are similar to those of

an acute subdural hematoma.

If the patient can be transported rapidly to the

hospital, an immediate craniotomy is performed to open the dura, allowing the

subdural clot to be evacuated. Successful outcome also de-pends on the control

of ICP and careful monitoring of respira-tory function. The mortality rate for

patients with acute and sub-acute subdural hematomas is high because of

associated brain damage.

Chronic Subdural Hematoma.

Chronic subdural

hematomas candevelop from seemingly minor head injuries and are seen most

frequently in the elderly. The elderly are prone to this type of head injury

secondary to brain atrophy, which is an expected con-sequence of the aging process.

Seemingly minor head trauma may produce enough impact to shift the brain

contents abnormally. The time between injury and onset of symptoms may be

lengthy (eg, 3 weeks to months), so the actual insult may be forgotten.

A chronic subdural hematoma resembles other conditions

and may be mistaken for a stroke. The bleeding is less profuse and there is

compression of the intracranial contents. The blood within the brain changes in

character in 2 to 4 days, becoming thicker and darker. In a few weeks, the clot

breaks down and has the color and consistency of motor oil. Eventually,

calcification or ossification of the clot takes place. The brain adapts to this

for-eign body invasion, and the clinical signs and symptoms fluctu-ate. There

may be severe headache, which tends to come and go; alternating focal

neurologic signs; personality changes; mental de-terioration; and focal

seizures. Unfortunately, the patient may be labeled neurotic or psychotic if

the cause of the symptoms is over-looked.

The treatment of a chronic subdural hematoma consists of

surgical evacuation of the clot. The procedure may be carried out through

multiple burr holes, or a craniotomy may be performed for a sizable subdural

mass that cannot be suctioned or drained through burr holes.

INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE AND HEMATOMA

Intracerebral

hemorrhage is bleeding into the substance of the brain. It is commonly seen in

head injuries when force is exerted to the head over a small area (missile

injuries or bullet wounds; stab injury). These hemorrhages within the brain may

also result from systemic hypertension, which causes degeneration and rup-ture

of a vessel; rupture of a saccular aneurysm; vascular anom-alies; intracranial

tumors; systemic causes, including bleeding disorders such as leukemia,

hemophilia, aplastic anemia, and thrombocytopenia; and complications of

anticoagulant therapy.

The onset may be

insidious, beginning with the development of neurologic deficits followed by

headache. Management includes supportive care, control of ICP, and careful

administration of fluids, electrolytes, and antihypertensive medications.

Surgical intervention by craniotomy or craniectomy permits removal of the blood

clot and control of hemorrhage but may not be possi-ble because of the

inaccessible location of the bleeding or the lack of a clearly circumscribed

area of blood that can be removed.

Management of Brain Injuries

Assessment and diagnosis

of the extent of injury are accomplished by the initial physical and neurologic

examinations. CT and MRI are the primary neuroimaging diagnostic tools and are

useful in evaluating soft tissue injuries. Positron emission tomography (PET

scan) is available in some trauma centers; this method of scanning examines

brain function rather than structure. A flow-chart developed by the Brain

Trauma Foundation for the initial management of brain-injured patients is

presented in Figure 63-4 (Brain Trauma Foundation, 2000).

Any individual with a

head injury is presumed to have a cer-vical spine injury until proven

otherwise. From the scene of the injury, the patient is transported on a board

with the head and neck maintained in alignment with the axis of the body. A

cervi-cal collar should be applied and maintained until cervical spine x-rays

have been obtained and the absence of cervical spinal cord injury documented.

All therapy is directed toward preserving brain

homeostasis and preventing secondary brain injury. “Secondary injury” is a term

used to describe injury to the brain subsequent to the orig-inal traumatic

event (Bader & Palmer, 2000). Common causes of secondary injury are

cerebral edema, hypotension, and respi-ratory depression that may lead to

hypoxemia and electrolyte imbalance. Treatments to prevent this include

stabilization of cardiovascular and respiratory function to maintain adequate

cerebral perfusion, control of hemorrhage and hypovolemia, and maintenance of

optimal blood gas values (Wong, 2000).

TREATMENT OF INCREASED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

As the damaged brain swells with edema or as blood

collects within the brain, a rise in ICP occurs; this requires aggressive

treatment. If the ICP remains elevated, it can decrease the CPP. Initial

management is based on the principle of preventing secondary injury and

maintaining adequate cere-bral oxygenation (see Fig. 63-4).

Surgery is required for

evacuation of blood clots, débridement and elevation of depressed fractures of

the skull, and suture of se-vere scalp lacerations. ICP is monitored closely;

if increased, it is managed by maintaining adequate oxygenation, elevating the

head of the bed, and maintaining normal blood volume. Devices to monitor ICP or

drain CSF can be inserted during surgery or at the bedside using aseptic

technique. The patient is cared for in the intensive care unit, where expert

nursing care and medical treatment are readily available.

SUPPORTIVE MEASURES

Treatment also includes ventilatory support, seizure

prevention, fluid and electrolyte maintenance, nutritional support, and pain

and anxiety management. Comatose patients are intubated and mechanically

ventilated to ensure adequate oxygenation and pro-tect the airway.

Because seizures are common after head injury and can cause secondary brain damage from hypoxia, antiseizure agents may be administered. If the patient is very agitated, benzodiazepines may be prescribed to calm him or her without decreasing LOC. These medications do not affect ICP or CPP, making them good choices for the head-injured patient.

A nasogastric tube may

be inserted because reduced gastric motility and reverse peristalsis are

associated with head injury, making regurgitation and aspiration common in the

first few hours.

BRAIN DEATH

When a patient has sustained a severe head injury

incompatible with life, the nurse may assist in the clinical examination for

determination of brain death and in the process of organ pro-curement. Since

1981, all 50 states have recognized the Uni-form Determination of Brain Death

Act (Lovasik, 2000). This act states that death will be determined with accepted

medical standards and that death will indicate irreversible loss of all brain

function. The patient has no neurologic activity upon clinical examination;

adjunctive tests such as EEG and cerebral blood flow (CBF) studies are often

used to confirm brain death (Lovasik, 2000). Many of these patients are

potential organ donors, and the nurse may provide information to the family and

assist them with this decision-making process about organ donation.

Related Topics