Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Antiinflammatory and Antirheumatic Drugs

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

NONSTEROIDAL

ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGS

The nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have a variety of

clinical uses as antipyretics, analgesics, and anti-inflammatory agents. They reduce body tem-perature

in febrile states and thus are effective an-tipyretics. They are also useful as

analgesics, relieving mild to moderate pain

such as myalgia, dental pain, dysmenorrhea, and headache. Unlike the

opioid analgesics, they do not cause neurological de-pression or dependence. As

anti-inflammatory agents, NSAIDs are used to treat conditions such as muscle

strain, tendinitis, and bursitis. They are also used to treat the chronic pain

and inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis (adult onset and juvenile),

osteoarthritis, and arthritic variants such as gouty arthritis and ankylosing

spondylitis. While NSAIDs used to be the sole agent of choice for mild to

moderate rheumatoid disease, they are now frequently used in conjunction with

the disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

(DMARDs) early in the treatment of these disorders. This is

because the NSAIDs reduce pain and

inflammation associated with rheumatoid diseases but do not delay or reverse

the dis-ease’s progress.

Mechanism of Action

The anti-inflammatory actions of the NSAIDs are most likely

explained by their inhibition of prostaglandin syn-thesis by COX-2. The COX-2 isoform is the

predomi-nant COX involved in the production of prostaglandins during

inflammatory processes. Prostaglandins of the E and F series evoke some of the

local and systemic man-ifestations of inflammation, such as vasodilation, hyper-emia,

increased vascular permeability, swelling, pain, and increased leukocyte

migration. In addition, they in-tensify the effects of inflammatory mediators,

such as histamine, bradykinin, and 5-hydroxytryptamine. All NSAIDs except the

COX-2-selective agents inhibit both COX isoforms; the degree of inhibition of

COX-1 varies from drug to drug. No one

NSAID is empirically superior for the

treatment of inflammatory diseases; in-stead, each individual’s response to and

tolerance of a drug determines its therapeutic utility.

Adverse Effects

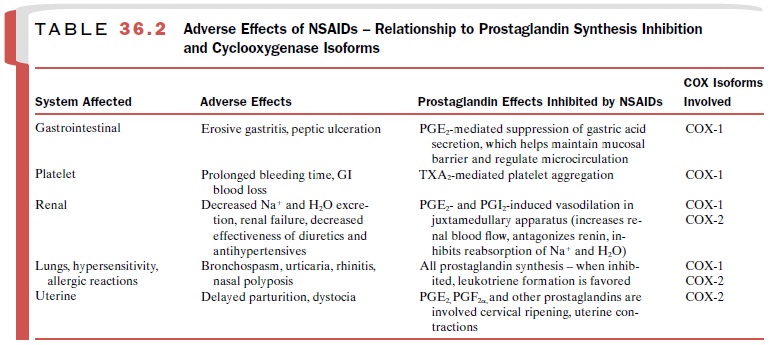

A number of the toxicities

commonly caused by the NSAIDs result from the inhibition of prostaglandin

synthesis (Table 36.2). The ability of

NSAIDs to increase gastric acid

secretion and inhibit blood clotting can lead to GI toxicity. Mild

reactions, such as heartburn and in-digestion, may be decreased by adjusting

the dosage, us-ing antacids, or administering the drugs after meals. Occult

loss of blood from the GI tract and iron defi-ciency anemia are also possible.

More serious toxicity can result from prolonged NSAID therapy, including peptic

ulceration and rarely, GI hemorrhage.

NSAIDs can impair renal function, cause fluid reten-tion, and

provoke hypersensitivity reactions, including

bronchospasm, aggravation of asthma, urticaria, nasal polyps, and rarely,

anaphylactoid reactions. These reac-tions may occur even in those who have

previously used NSAIDs without any ill effects. NSAIDs inhibit uterine

contraction and can cause premature closure of the fe-tal ductus arteriosus.

The spectrum of toxicity

produced by each NSAID is related to its inhibition of specific COX isoforms.

The earliest NSAIDs inhibit both isoforms of COX. Certain of these drugs are

more specific for COX-1, whereas oth-ers inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 with roughly

equal po-tency. More recently developed

drugs selectively inhibit COX-2 and

therefore do not elicit the GI and antiplatelet side effects common to drugs

that inhibit COX-1.

Adverse effects that are not

unequivocally related to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis include hepatic

effects (hepatitis, hepatic necrosis, cholestatic jaundice, increased serum

aminotransferases), dermal effects (photosensitivities, Stevens-Johnson

syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, onycholysis), central nervous sys-tem

(CNS) effects (headaches, dizziness, tinnitus, deaf-ness, drowsiness,

confusion, nervousness, increased sweating, aseptic meningitis), ocular effects

(toxic am-blyopia, retinal disturbances), and certain renal effects (acute

interstitial nephritis, acute papillary necrosis).

Contraindications and Drug Interactions

Co-morbid factors that increase the risk of NSAID-induced GI bleeding include history of ulcer disease, advanced age, poor health status, treatment with certain drugs (discussed later), long duration of NSAID ther-apy, smoking, and heavy alcohol use. Because of their renal effects, NSAIDs must be used with caution in patients with renal impairment, heart failure, hyperten-sion, and edema.

The use of NSAIDs is

contraindicated in persons who have had a hypersensitivity reaction to

salicylates or any other NSAID. Asthmatics are at par-ticular risk for these

reactions. NSAIDs should be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit

justifies the risk to the fetus.

A significant number of drug

interactions are com-mon to most of the NSAIDs. The likelihood of NSAID-induced

GI toxicity is increased by concomitant treat-ment with corticosteroids (long

term), other NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, or anticoagulants. Certain NSAIDs can

also compete for protein binding sites with war-farin, compounding the risk of

GI bleeding if these drugs are coprescribed. Agents that cause

thrombocy-topenia (e.g., myelosuppressive antineoplastic drugs) can also

increase the likelihood that NSAIDs will cause bleeding. NSAIDs can decrease

the clearance of methotrexate, resulting in severe hematological and GI

toxicity. This does not appear to be a significant problem with low-dose

methotrexate used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis; however, higher

methotrexate doses used in the treatment of psoriasis or cancer may produce

this toxicity. NSAIDs, when used in conjunc-tion with immunosuppressive agents,

can mask fever and other signs of infection.

Because NSAIDs decrease

prostaglandin synthesis in the kidney, these drugs can increase the nephrotox- icity

of agents such as aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, cidofovir, cisplatin,

cyclosporine, foscarnet, ganci-clovir, pentamidine, and vancomycin. NSAIDs can

de-crease the renal excretion of drugs such as lithium. NSAIDs can decrease the

effectiveness of antihyper-tensive drugs such as β-blockers and diuretics. The

eld-erly and those with decreased renal function are at particular risk for

this interaction. Elevated hepatic enzymes and hepatic toxicity can occur with

some drugs.

Related Topics