Chapter: Introduction to Botany: The Origin of Trees and Seeds

Life Forms - The Origin of Trees and Seeds

Life Forms

The most ancient classification of plants divided them into trees, shrubs and herbs. This approach was the first classification of life forms. Life forms tell not about evolution, but about how plant lives. We still use this classification. With some modifications, it plays a significant role in gardening:

Vines Climbing woody and herbaceous plants

Trees Woody plants with one long-lived trunk

Shrubs Woody plants with multiple trunks

Herbs Herbaceous plants, with no or little secondary xylem (wood). Sometimes,divided further into annuals (live one season), biennials (two seasons) and perennials.

This classification system has many downfalls. What is, for example, the rasp-berry? It has woody stems but each of them lives only two years, similar to bien-nial herbs. Or what is duckweed? These small, water-floating plants with ovate non-differentiated bodies are hard to call “herbs”. As one can see, the actual diversity of plant lifestyles is much wider than the classification above.

Dynamic Approach

This classification uses the fact that, in nature, there are no strict borders be-tween different life forms. If we supply the pole to some shrubs, they may start to climb and therefore become vines. In colder regions, trees frequently lose their trunks due to low temperatures and form multiple short-living trunks: they become shrubs. Conversely, in tropics, many plants which are herbs in temper-ate regions, will have time to develop secondary tissues and may even become tree-like.

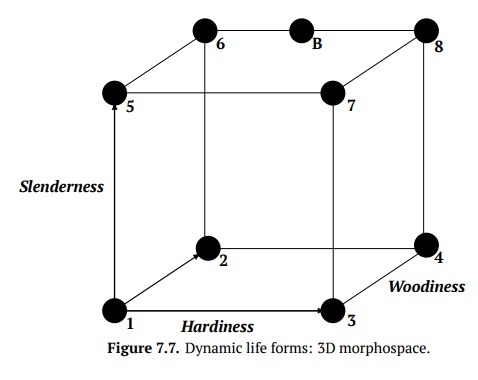

Dynamic approach uses three categories: hardiness, woodiness, and slender-ness (Fig. 7.7). Hardiness is a sensitivity of their exposed parts to all negative influences (cold, heat, pests etc.) This is reflected in the level of plant exposure, plants which are hardy will expose themselves much better. Woodiness is the ability to make dead tissues, both primary and secondary (reflected in the per-centage of cells with secondary walls). High woodiness means that plants will be able to support themselves without problems. Slenderness is an ability to grow in length (reflected in the proportion of linear, longer than wide, stems). Low slenderness results in rosette-like plants. Combining these three categories in different proportions, one may receive all possible life forms of plants.

These three categories could be used as variables of the 3D morphospace. Every numbered corner in the morphospace diagram (Fig. 7.7) represents one extreme life form:

1. Reduced floating annuals like duckweed (Lemna). Please note that zero hardiness is impossible; duckweed hardiness is just low.

2. Short annual herbs like marigold (Tagetes); they accumulate wood if warm season is long enough.

3. Bulb perennials like autumn crocus (Colchicum).

4. Australian “grass trees” (Xanthorrhea) with almost no stem but long life.

5. Herbaceous vines like hops (Humulus).

6. Monocarpic tree-like plants like mezcal agave (Agave).

7. Perennial ground-cover herbaceous plants like wild ginger (Asarum).

8. Trees like redwood (Sequoia).

What is even more important, all possible positions on the “surface” and inside this cube also represent life forms. For example, the dot marked with “B” are slender, woody but only partly hardy plants. The partial hardiness means that vertical axes will frequently die, and then new slender woody axes develop from scratch. Woody wines and creeping bushes will correspond well with this de-scription. As you see, this morphospace not only classifies existing plants but also could predict possible life forms.

Raunkiaer’s Approach

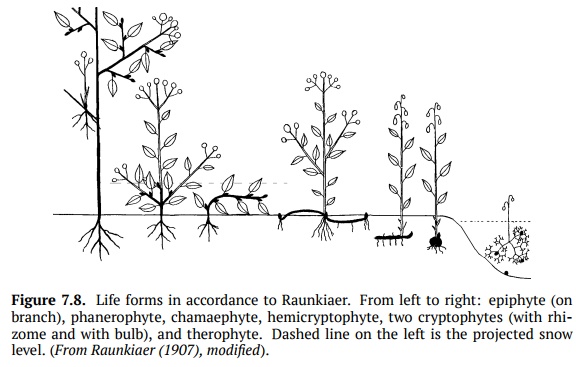

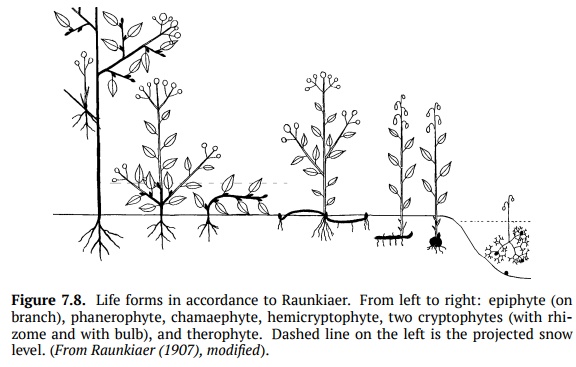

Christen Raunkiaer used a different approach to classify life forms which is use-ful to characterize the whole floras (all plant species growing on some terri-tory), especially temperate floras. He broke plants down into six categories: epiphytes, phanerophytes, chamaephytes, hemicryptophytes, cryptophytes and therophytes.

Epiphytes do not touch soil (they are aerial plants), phanerophytes have their win-ter buds exposed, chamaephytes “put” their winter buds under the snow, winter buds ofhemicryptophytes on the soil surface, cryptophytes in the soil and/or under water, and therophytes do not have winter buds, they go through winter as seeds (Fig. 7.8). Typically, northern floras have more plants of last categories whereas first categories will dominate southern floras. Note that Raunkiaer “bud expo-sure” is not far from the hardiness in the dynamic approach explained above.

Architectural Models Approach

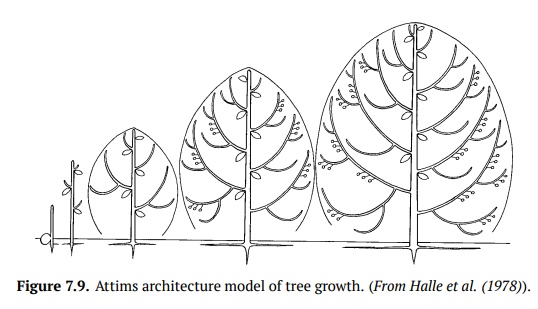

During the winter, it is easy to see that some tree crowns have similar principles of organization. In the winter-less climates, the diversity of these structures is even higher. On the base of branching (monopodial or sympodial), location of FU, and direction of growth (plagiotropic, horizontal or orthotropic, vertical), multiple architectural models were described for trees. Each model was named after a famous botanist such as Thomlinson, Cook, Attims, and others. In tem-perate regions, one of the most widespread models is Attims (irregular sympo-dial growth): birches (Betula) and alders (Alnus) grow in accordance with that model (Fig. 7.9).

Related Topics