Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Clinical Pharmacology: Intravenous Anesthetics

Intravenous Anesthetics: Propofol

PROPOFOL

Mechanisms of Action

Propofol induction of general anesthesia

may involve facilitation of inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABA A receptor binding. Propofol allo-sterically

increases binding affinity of GABA for the GABAA

receptor. This receptor, as previously noted, is coupled to a chloride channel,

and activation of the receptor leads to hyperpolarization of the nerve

membrane. Propofol (like most general anesthetics) binds multiple ion channels

and receptors. Propofol actions are not reversed by the specific

benzodiaz-epine antagonist flumazenil.

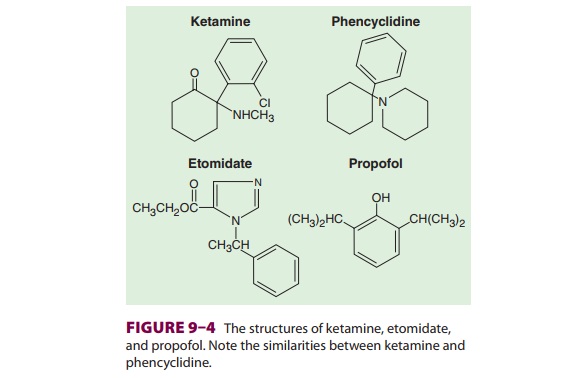

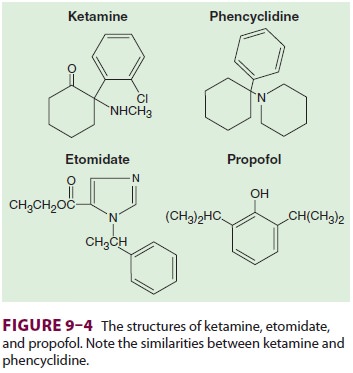

Structure–Activity Relationships

Propofol consists of a phenol ring

substituted with two isopropyl groups (see Figure 9–4). Propofol is not water

soluble, but a 1% aqueous solution (10 mg/mL) is available for intravenous

administration as an oil-in-water emulsion containing soybean oil, glycerol,

and egg lecithin. A history of egg allergy does not necessarily contraindicate

the use of pro-pofol because most egg allergies involve a reaction to egg white

(egg albumin), whereas egg lecithin is extracted from egg yolk. This

formulation will often cause pain during injection that can be decreased by

prior injection of lidocaine or less effectively by mixing lidocaine with

propofol prior to injection (2 mL of 1% lidocaine in 18 mL propofol). Propofol

formulations can support the growth of bacteria, so sterile technique must be

observed in preparation and handling. Propofol should be administered within 6

h of opening theampule. Sepsis and death have been linked to con-taminated

propofol preparations. Current formula-tions of propofol contain 0.005%

disodium edetate or 0.025% sodium metabisulfite to help retard the rate of

growth of microorganisms; however, these additives do not render the product

“antimicrobi-ally preserved” under United States Pharmacopeia standards.

Pharmacokinetics

A. Absorption

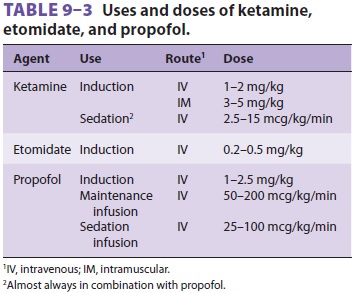

Propofol is available only for

intravenous adminis-tration for the induction of general anesthesia and for

moderate to deep sedation (see Table 9–3).

B. Distribution

Propofol has a rapid onset of action.

Awakening from a single bolus dose is also rapid due to a very short initial

distribution half-life (2–8 min). Most investigators believe that recovery from

propofol is more rapid and is accompanied by less “hangover” than recovery from

methohexital, thiopental, ket-amine, or etomidate. This makes it a good agent

for outpatient anesthesia. A smaller induction dose is recommended in elderly

patients because of their smaller Vd. Age is also a key factor determining required

propofol infusion rates for TIVA. In coun-tries other than the United States, a

device called the Diprifusor is often used to provide target (con-centration)

controlled infusion of propofol. The user must enter the patient’s age and

weight and the desired target concentration. The device uses these data, a

microcomputer, and standard phar-macokinetic parameters to continuously adjust

the infusion rate.

C. Biotransformation

The clearance of propofol exceeds hepatic

blood flow, implying the existence of extrahepatic metabo-lism. This

exceptionally high clearance rate probably contributes to relatively rapid

recovery after con-tinuous infusions. Conjugation in the liver results in

inactive metabolites that are eliminated by renal clearance. The

pharmacokinetics of propofol do not appear to be affected by obesity,

cirrhosis, or kidney failure. Use of propofol infusion for long-term seda-tion

of children who are critically ill or young adultneurosurgical patients has

been associated with spo-radic cases of lipemia, metabolic acidosis, and death,

the so-termed propofol infusion syndrome.

D. Excretion

Although metabolites of propofol are

primarily excreted in the urine, chronic kidney failure does not affect

clearance of the parent drug.

Effects on Organ Systems

A. Cardiovascular

The major cardiovascular effect of

propofol is a decrease in arterial blood pressure due to a drop in systemic

vascular resistance (inhibition of sympathetic vasoconstrictor activity),

preload, and cardiac con-tractility. Hypotension following induction is usually

reversed by the stimulation accompanying laryngos-copy and intubation. Factors

associated with propo-fol-induced hypotension include large doses, rapid

injection, and old age. Propofol markedly impairs the normal arterial

baroreflex response to hypotension. Rarely, a marked drop in preload may lead

to a vagally mediated reflex bradycardia. Changes in heart rate and cardiac

output are usually transient and insignificant in healthy patients but may be

severe in patients at the extremes of age, those receiving β-adrenergic

blockers, or those with impaired ventricular function. Although myocardial

oxygen consumption and coronary blood flow usually decrease comparably,

coronary sinus lac-tate production increases in some patients, indicating some

mismatch between myocardial oxygen supply and demand.

B. Respiratory

Propofol is a profound respiratory

depressant that usually causes apnea following an induction dose. Even when

used for conscious sedation in sub-anesthetic doses, propofol inhibits hypoxic

venti-latory drive and depresses the normal response to hypercarbia. As a

result, only properly educated and qualified personnel should administer

propofol for sedation. Propofol-induced depression of upper airway reflexes

exceeds that of thiopental, allowing intubation, endoscopy, or laryngeal mask

placement in the absence of neuromuscular blockade. Although propofol can cause

histamine release, induction with propofol is accompanied by a lower incidence

of wheezing in asthmatic and nonasthmatic patients compared with barbiturates

or etomidate.

C. Cerebral

Propofol decreases cerebral blood flow

and intracra-nial pressure. In patients with elevated intracranial pressure,

propofol can cause a critical reduction in CPP (<50 mm Hg) unless steps are taken to support mean

arterial blood pressure. Propofol and thiopen-tal probably provide a similar

degree of cerebral pro-tection during experimental focal ischemia. Unique to

propofol are its antipruritic properties. Its anti-emetic effects (requiring a

blood propofol concen-tration of 200 ng/mL) provide yet another reason for it

to be a preferred drug for outpatient anesthesia. Induction is occasionally

accompanied by excitatory phenomena such as muscle twitching, spontaneous

movement, opisthotonus, or hiccupping. Although these reactions may

occasionally mimic tonic–clonic seizures, propofol has anticonvulsant

properties and has been used successfully to terminate status epi-lepticus.

Propofol may be safely administered to epileptic patients. Propofol decreases

intraocular pressure. Tolerance does not develop after long-term propofol

infusions. Propofol is an uncommon agent of physical dependence or addiction;

however, both anesthesia personnel and medically untrained indi-viduals have

died while using propofol inappropri-ately to induce sleep in nonsurgical

settings.

Drug Interactions

Fentanyl and alfentanil concentrations

may be increased with concomitant administration of pro-pofol. Many clinicians

administer a small amount of midazolam (eg, 30 mcg/kg) prior to induction with

propofol; midazolam can reduce the required pro-pofol dose by more than 10%.

Related Topics